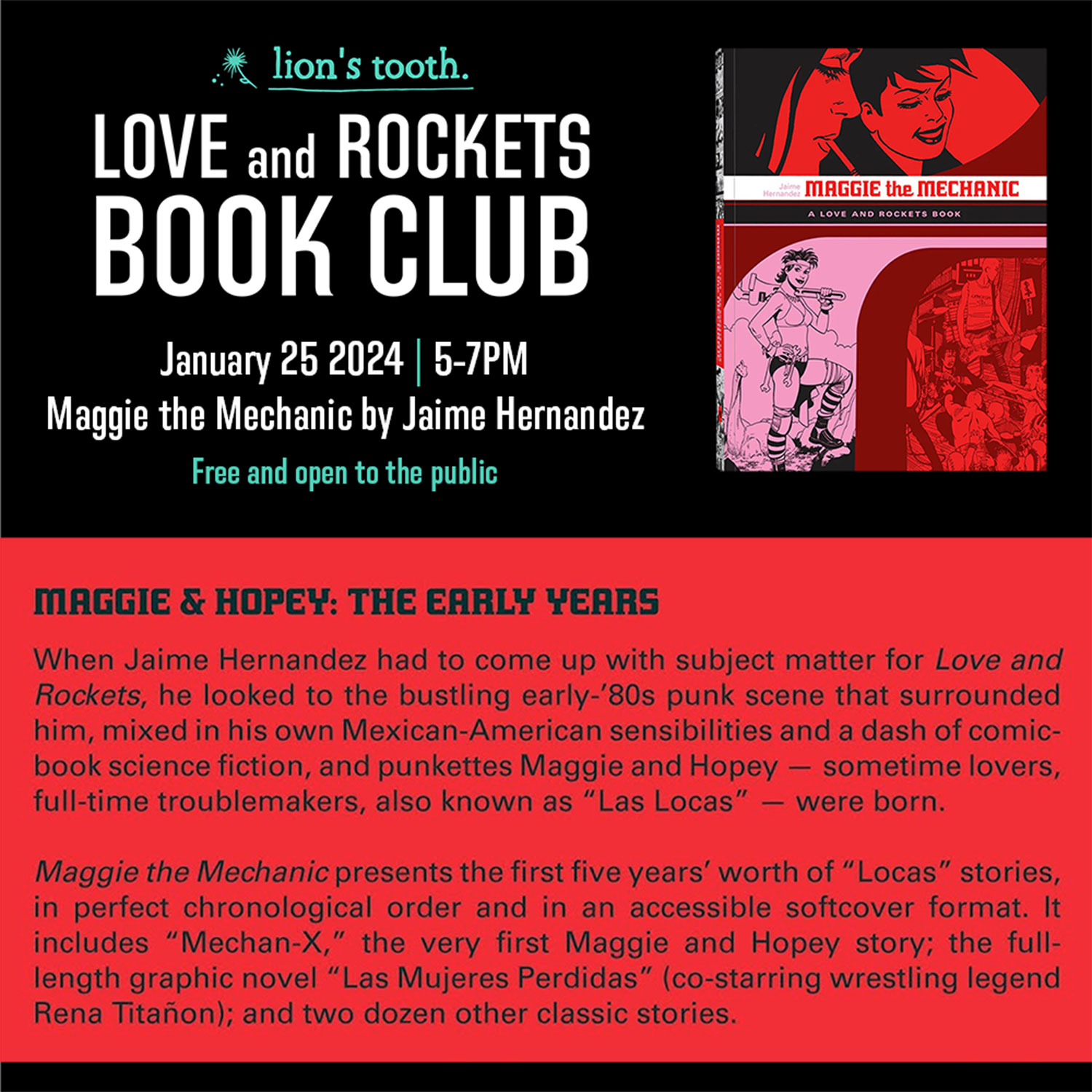

The title of this article (“20 Years Later”) refers to a series of conversations starting in 2017, with cartoonists I had first met in 1997. I’ve been posting these new interviews here in Milwaukee Record over the last few years, but COVID made an already delayed project even slower. This particular talk with Jaime Hernandez happened in Los Angeles in February 2020, days before the pandemic grounded the world. The text is adapted from an introduction for the Brazilian edition of Maggie The Mechanic, a collection of comics by Jaime which is also the first title we will read at Lion’s Tooth for a new in-store book club premiering on January 25, 2024. Please join us for that! More info HERE.

I‘ve been a die-hard Love And Rockets enthusiast for almost 30 years, since I was a teenager. The magazine by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez (and at first and occasionally by their older brother Mario) was the catalyst that transformed my childhood fixation with comic books into a constant in adult life. Jaime’s comics, in particular, have been an influence on all of my artistic experiments, from my own drawings, to a short film that attempted to reproduce the comic’s black-and-white aesthetic, to my time in São Paulo’s underground scene. My first band was called Go Hopey, my comic book store at the time was called Vida Loca, even my dogs were called Maggie and Speedy, all homages to characters and elements from Jaime’s comics. My first tattoo is Hopey, too (the second is Luba, Gilbert’s character). You get the idea. I hope this brief recap does justice to the comics that transformed the indie scene in the United States, and changed my life too.

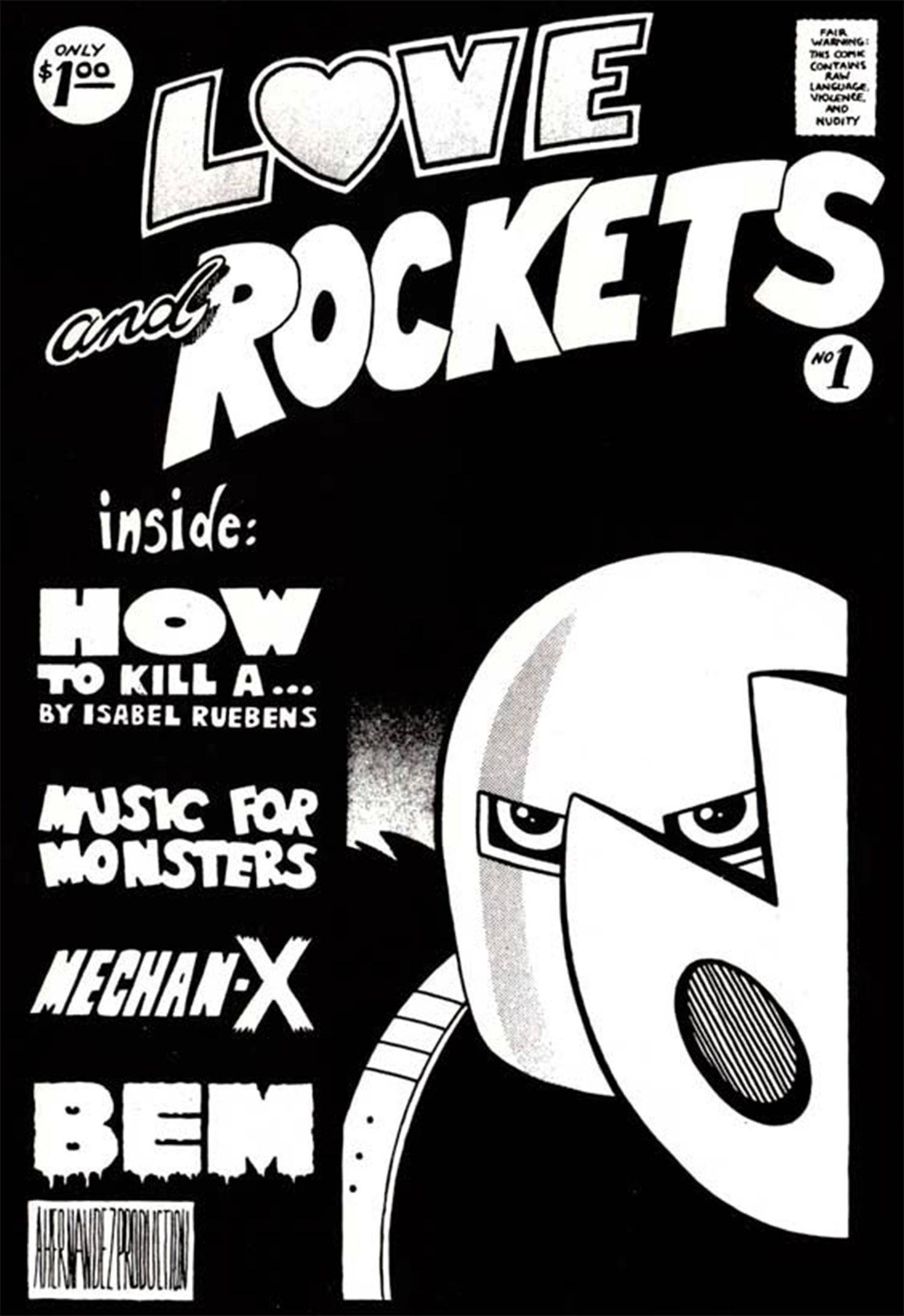

The story of Love And Rockets is a fairy tale of the world of underground comics. In 1981, brothers Mario, Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez sent a copy of their homemade fanzine to the renowned periodical The Comics Journal, hoping to receive a positive review. The response was an invitation from editor Gary Groth to publish the magazine, which became (and is to this day) the flagship title of Fantagraphics, the most well respected North American publisher of art comics.

Cover of the zine version of Love And Rockets, with art by Gilbert Hernandez

It’s difficult to imagine the impact this had on a 22-year-old kid who dreamed of being a cartoonist since childhood, with the skillset to work at Marvel or DC, but who took the risk of telling personal stories with Latine characters, almost completely absent from comic books at the time. The universe that Jaime created in Love And Rockets is based on his youth in Southern California. The Huerta/Hoppers 13 neighborhood where the protagonist Maggie and her friends (nicknamed “locas”) live is a fictional Hispanic community based on the city of Oxnard, where the Hernandez kids grew up.

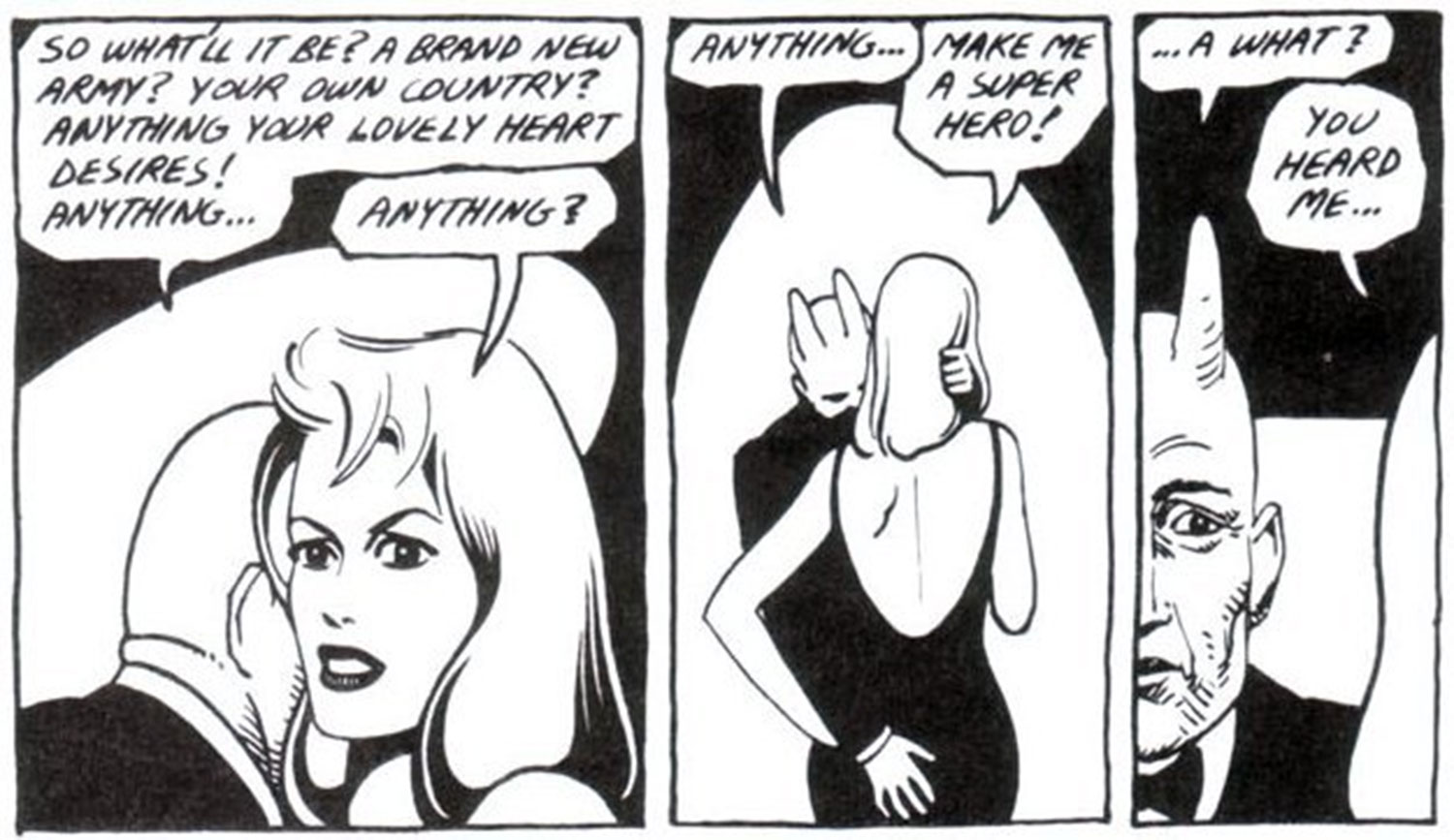

Jaime is the fourth of six children, all men, with the exception of an older sister. “I’m always the little brother when I talk about memories,” he says. “I was the kid who didn’t know what was going on all the time.” The kids grew up watching their mother draw portraits inspired by classic comics. “When she showed them to us, a lot of the characters were Golden Age characters, superheroes, and from Adventure Comics. I didn’t know who they were, and she would point out: ‘Oh, this character used to do this. This one used to do that.’ To me, maybe to my brothers too, they seemed almost like movie stars. ‘Who’s this guy with the black mask?’ ‘Oh, that’s the Black Terror.’ ‘Ooh, this guy must be cool!’ There was something really romantic about it.” No wonder Jaime’s character Penny Century is obsessed with becoming a superhero, the only thing her horned lover H.R. Costigan can’t buy for her, despite being the richest man in the world.

Penny Century asks her rich lover to make her a superhero

Recognition may have come early, but it took some time for Jaime to be able to make a living exclusively from Love And Rockets. “The comic book was the steady stream. I was always going to do comics, no matter if I did something on the side, like illustration work for magazines,” he says. “I knew I would always come back to the comic. I’ve never given it up.” In fact, the Hernandez brothers took the magazine seriously from the beginning. “When we started the comic, we had this built-in responsibility,” he explains. “This will sound really goofy. When we started the comic, and we were going to be published professionally, I thought, ‘Well, professionals are grownups, aren’t they?’ I had this almost naiveté of like, ‘Okay, I have to stand by my work. I have to be a grown-up doing this. Even if the comic has silly stuff, even if the comic has dumb rocket chips or silly punk rockers, I still got to handle it like a grownup would.’”

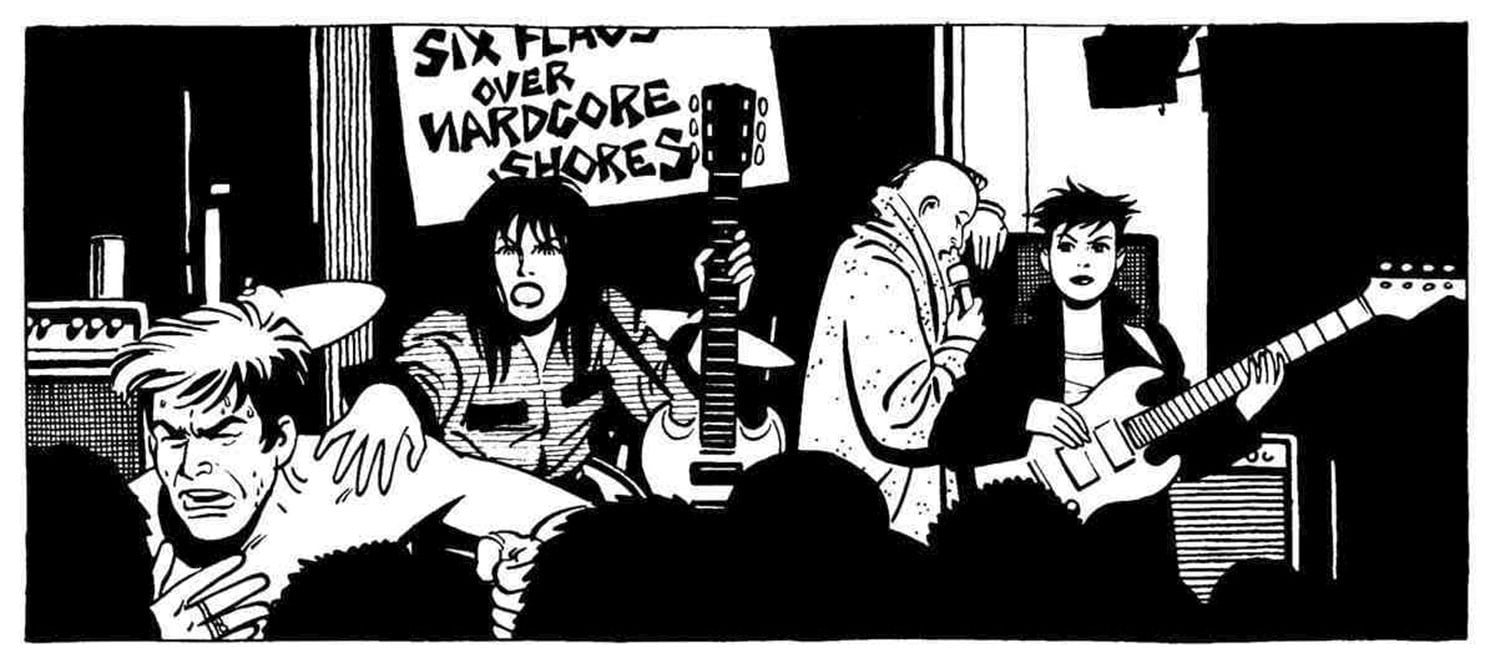

Like the “locas” girls, the Hernandez brothers were part of the local punk scene, which influenced not only the setting of Jaime’s stories but also the tone of his comics. “Punk is honest and direct without a lot stuff hidden behind fanciness. I know that’s not only punk, but that’s where I got it. Where I was to be direct, tell the truth. You’re writing for [the readers]. Don’t make them have to fight to read this thing. Just tell it directly, they will understand right away”, he says. “You don’t have to go see the band in a giant stadium where they’re far away on the stage. You can go in a club and the band is right there. Five minutes ago, they were in the audience hanging out. It was just kind of like, ‘Yes, this is cool, I’m part of it.’ That’s kind of the approach I took for doing this stuff. I want you to be part of it. Without dumbing it down. Without making it simple.”

The character Hopey (on bass) and her band

The focus on this niche of punks in a Latine community doesn’t prevent Jaime’s work from having a universal appeal that is rare in comics, indie or otherwise. “The way I write it, is like, look, the whole world’s going to look at this,” he says. “Yes, I’m doing these comics about this small Southern California neighborhood, but I want people across the world to get it, or to at least see it as a real thing.” If this is difficult to find today, it was virtually non-existent when Love And Rockets first emerged. Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez invented a new way of making indie comics, which would eventually reach a wider audience than the underground work that came before.

Until around the year 2000, almost every article about adult comics came with the warning “comics aren’t just for kids anymore,” and few people considered the medium to be a legitimate form of artistic expression. Things are very different today. Comic books became “graphic literature” (the Portuguese equivalent of “graphic novel”), complete with reviews and confetti in the literary section of mainstream outlets. The Hernandez brothers and many of their contemporaries have received retrospectives at major art museums. There is no longer any question as to whether comics are art, much less whether they are just for kids.

“There are more comics in people’s lives now, I think. It’s more normal than it used to be,” Jaime says. “I remember being on panels or conventions and it always ended up with, ‘How do we get comics into bookstores?’ and I just went, ‘Okay, panel’s over.’ [laughter] Now comics are in bookstores”.

Alternative production has also changed a lot in recent years. “Comics are different today than the alternative market in the ’80s, when we started,” he says. “It’s different, like you have the mini comic people. You have the people who only do a graphic novel, they only do a hardcover book, 500 pages. You have very few who prefer to do it just like a comic book [magazine], like us. They’re still out there, but it’s just very few and far between. You have people who do it on a computer. You have them post it on the internet. You have people who do comics for the computer, not for paper.”

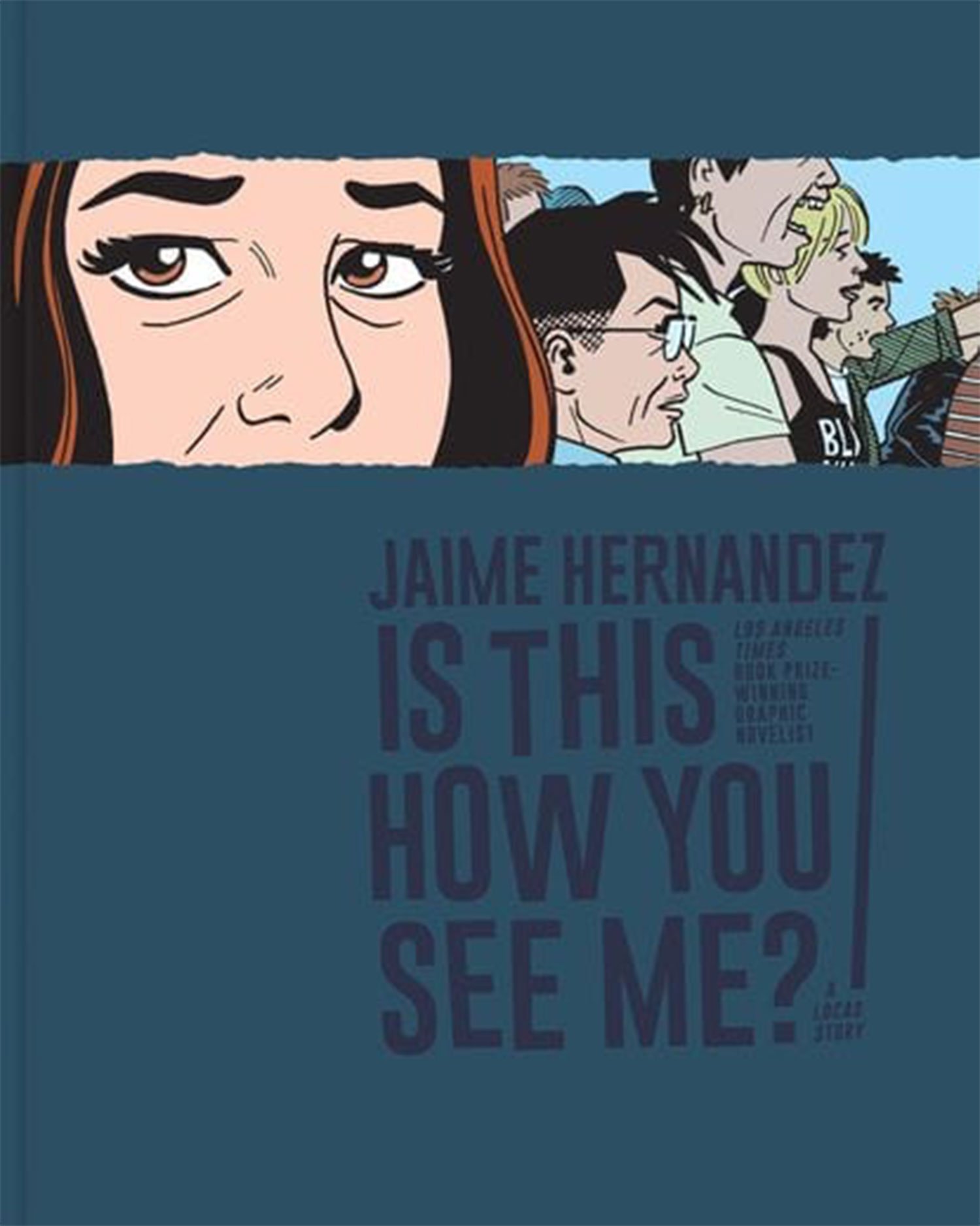

Cover of Is This How You See Me?, Jaime’s 2019 book collection

Amid all these changes, Love And Rockets remains faithful to its origins. In 2016, the magazine started once again to be published as a periodical floppy, with the stories organized into volumes later. “I’m from the old school, I just liked the comics,” Jaime says. “I like the comic form, I like the whole look of it. [People say] ‘You use such grown-up themes and such—It’s not just comic books.’ No, no, no, no, it is a comic book. This is just a good one,” he says, laughing.

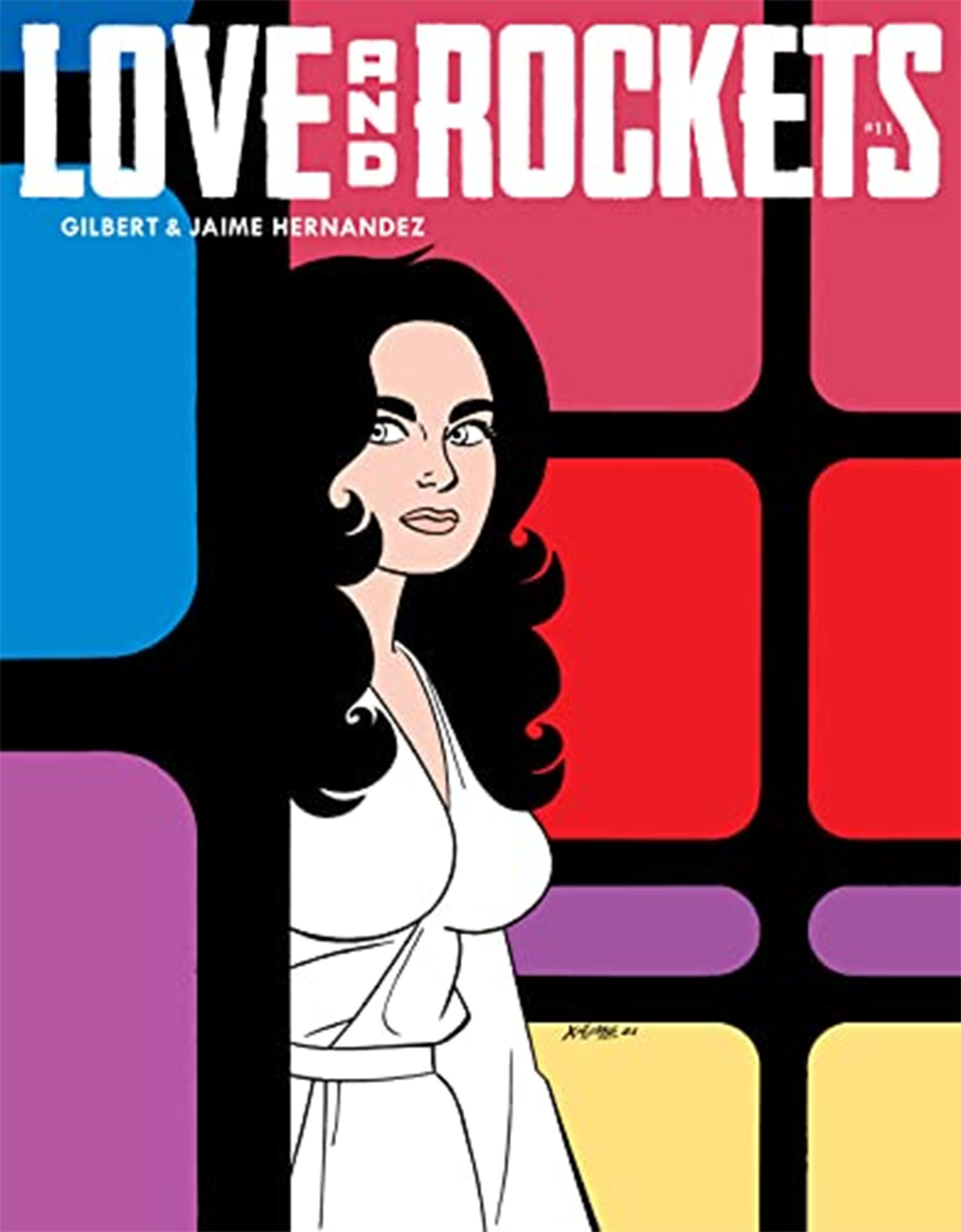

Cover of a recent Love And Rockets floppy comic (Number 11, Vol. IV)

At first Jaime experimented with science fiction, through Maggie’s adventures as a prosolar mechanic apprentice, repairing robots and spaceships. Over time, the narrative moved away from fantastic settings and exotic lands to focus on psychological dilemmas, mainly of Maggie herself, who is a mix of Jaime’s muse and alter ego. Today Jaime continues to draw the life of Maggie, now in her 50s. This biographical perspective emerged early, when the character gained a few pounds and time began to pass realistically in the stories. Fans don’t always like what happens in the comic, especially the ups and downs of the friendship-romance between Maggie and her sidekick Hopey, but Jaime says he likes to get readers’ reactions even when they don’t agree with the direction of the story. “I appreciate it because that just tells me they care. If they didn’t care, then I’d worry.”

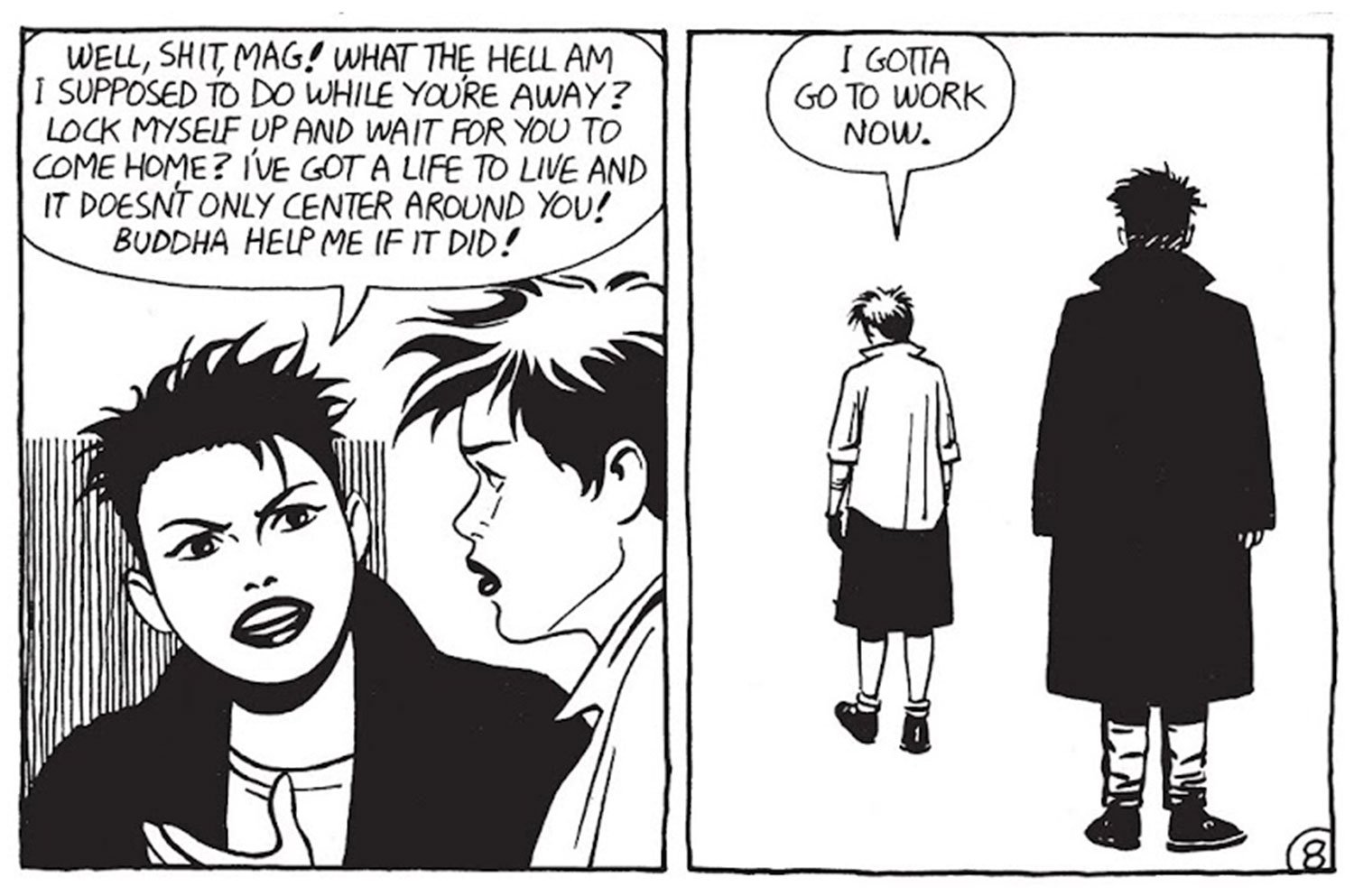

Young Maggie and Hopey

Which brings me to one of my favorite memories. A few years ago I was visiting Sorocaba (a city near São Paulo) as a volunteer at Girls Rock Camp Brazil. The event organizer set up a house with a swimming pool for the volunteers. There we were, 40 punk rockers from all over the country, basking in the sun the day before camp started. I saw that one of the ladies had a tattoo of Maggie, and we started talking about Love And Rockets. Right away we referred to the “locas” crew as if they were real people, mutual friends, and there was a lot of gossip to catch up on, because she had only read the Brazilian editions of the magazine. A small group gathered around us, wanting to know what happened to Maggie and Hopey in the last three decades, until it became a kind of meeting of minds touched by Jaime’s imagination. We shed some sweet tears in that pool.

“My heart’s like spilling when I’m [drawing the comic],” Jaime says. “I want the reader to feel the same way I do writing it. It’s tricky, but I try to put all of my feelings into that one scene. […] I don’t care. If it ain’t emotional for me, it’s not going to be for me.”

Drawing made at Comic Con in 1997, when Jaime sketched me in the style of my “loca” friends (note how nervous I was!)

Exclusive articles, podcasts, and more. Support Milwaukee Record on Patreon.

RELATED ARTICLES

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Megan Kelso

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Eric Reynolds

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Peter Bagge

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Dame Darcy