It has actually been 26 years since I first met cartoonist Megan Kelso in Seattle while touring the U.S. to interview my comics heroes for a Brazilian newspaper. The title “20 Years Later” refers to when I started retracing that path and meeting the same people again, this time as an American citizen living in Milwaukee. Some of these new interviews are available here in Milwaukee Record, but the project went dormant with COVID.

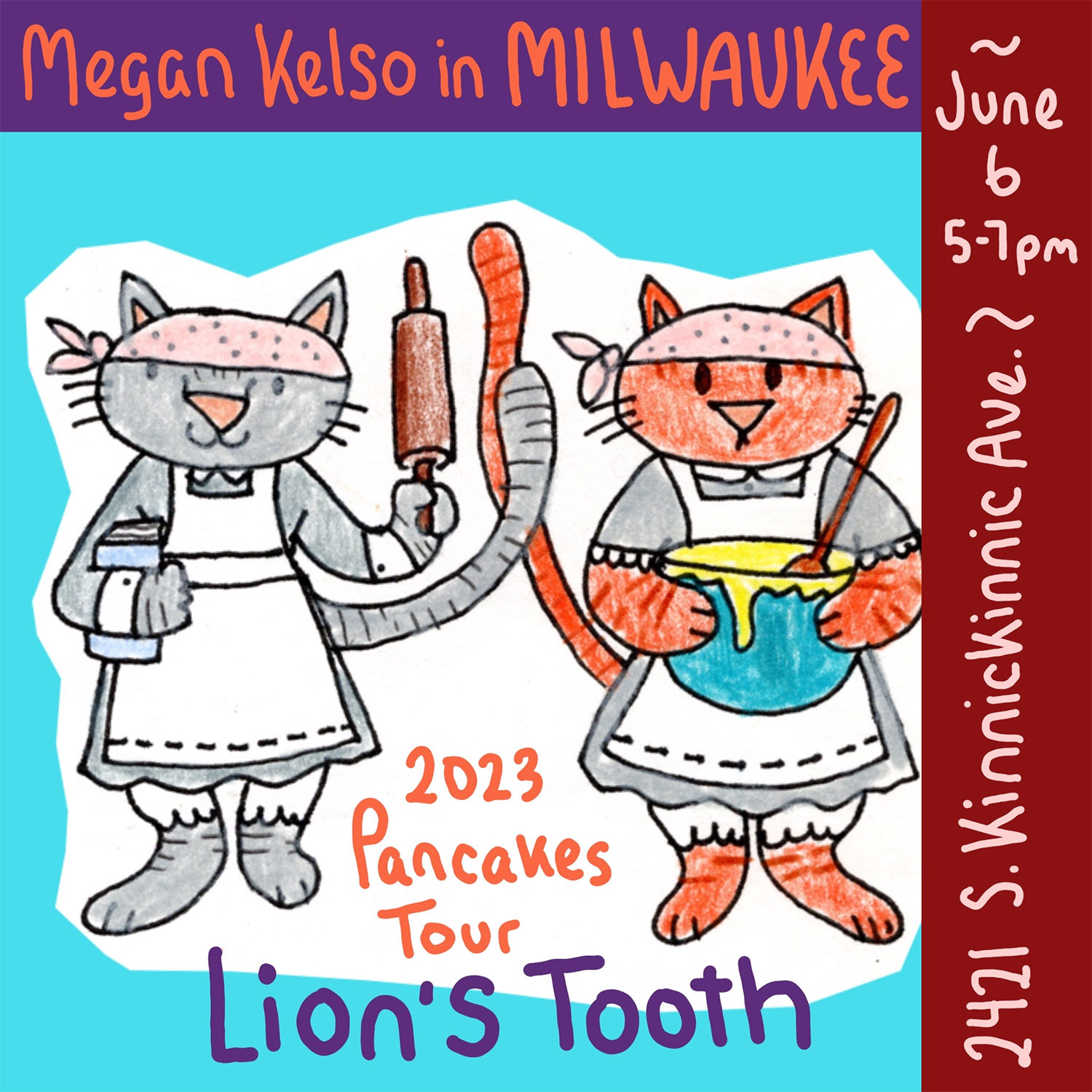

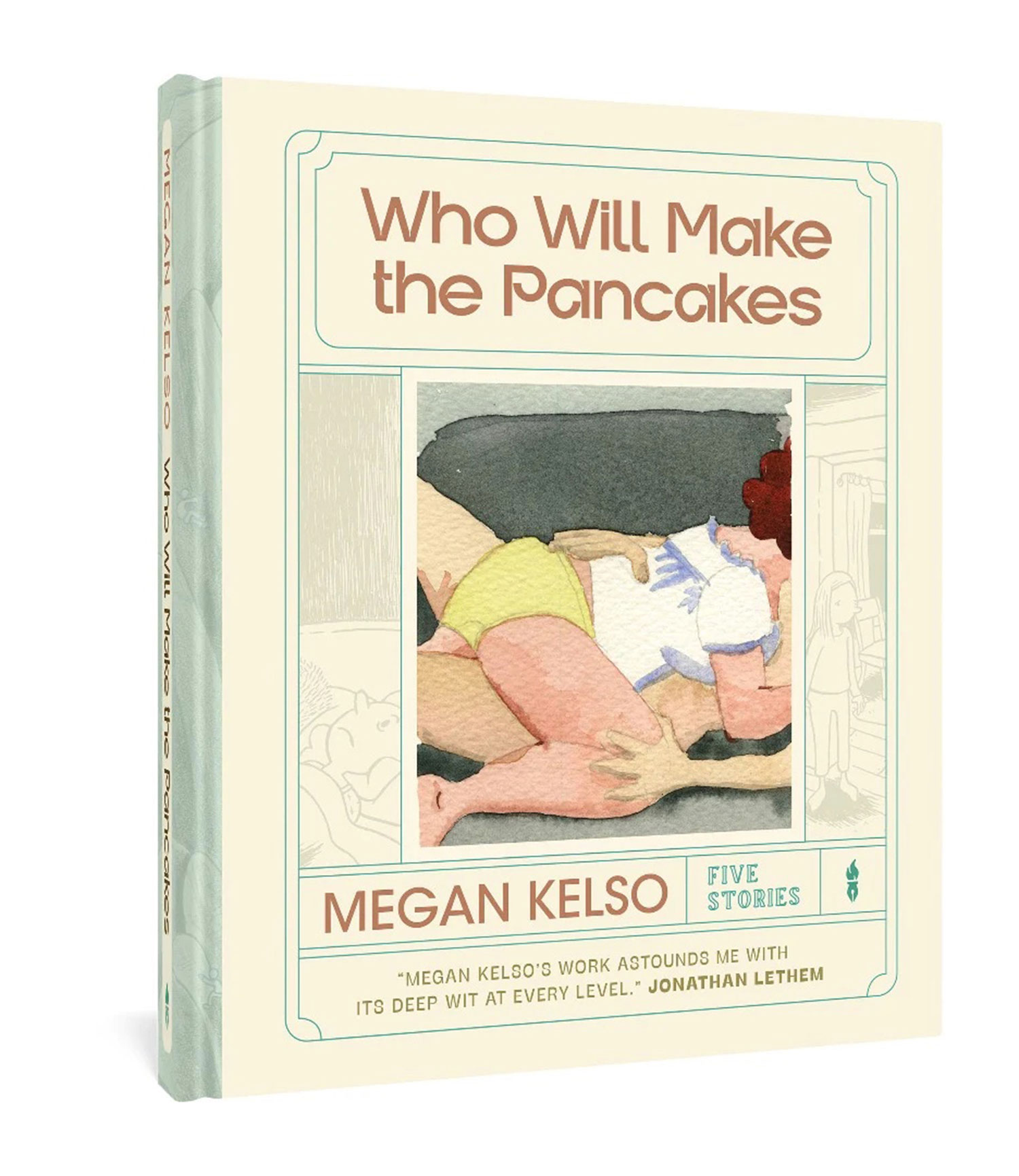

Now Megan is coming to Lion’s Tooth as part of the tour for Who Will Make The Pancakes: Five Stories, her latest book published by Fantagraphics. This is a big deal for me, as she is the first of the cartoonists I met in my youth to visit the Bay View bookstore and dream project I started during the pandemic with my business partner Shelly McClone-Carriere.

When I first talked to Megan in the summer of 1997, she was one of the few women in indie comics, though that seemed to be changing at the time. In that original conversation she told me, “I’ve given many interviews just because I am a woman, but thankfully the number of female cartoonists is growing, so it isn’t a novelty anymore.” The title of the article, which included other young talent of that era, was “Brilliant and unknown… for now.” Time has vindicated that arguably cringeworthy headline, most notably in the case of Adrian Tomine, also featured in the piece.

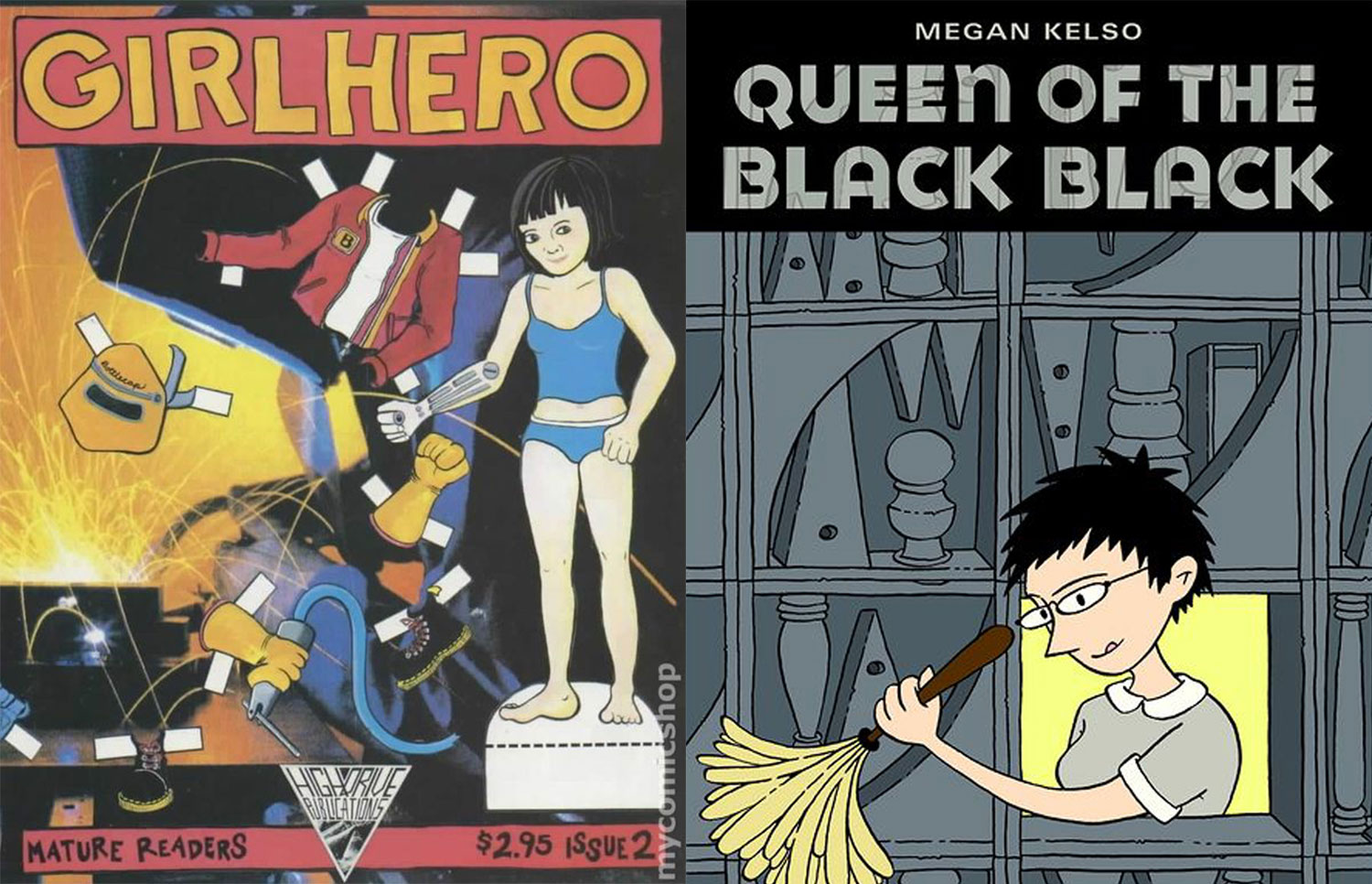

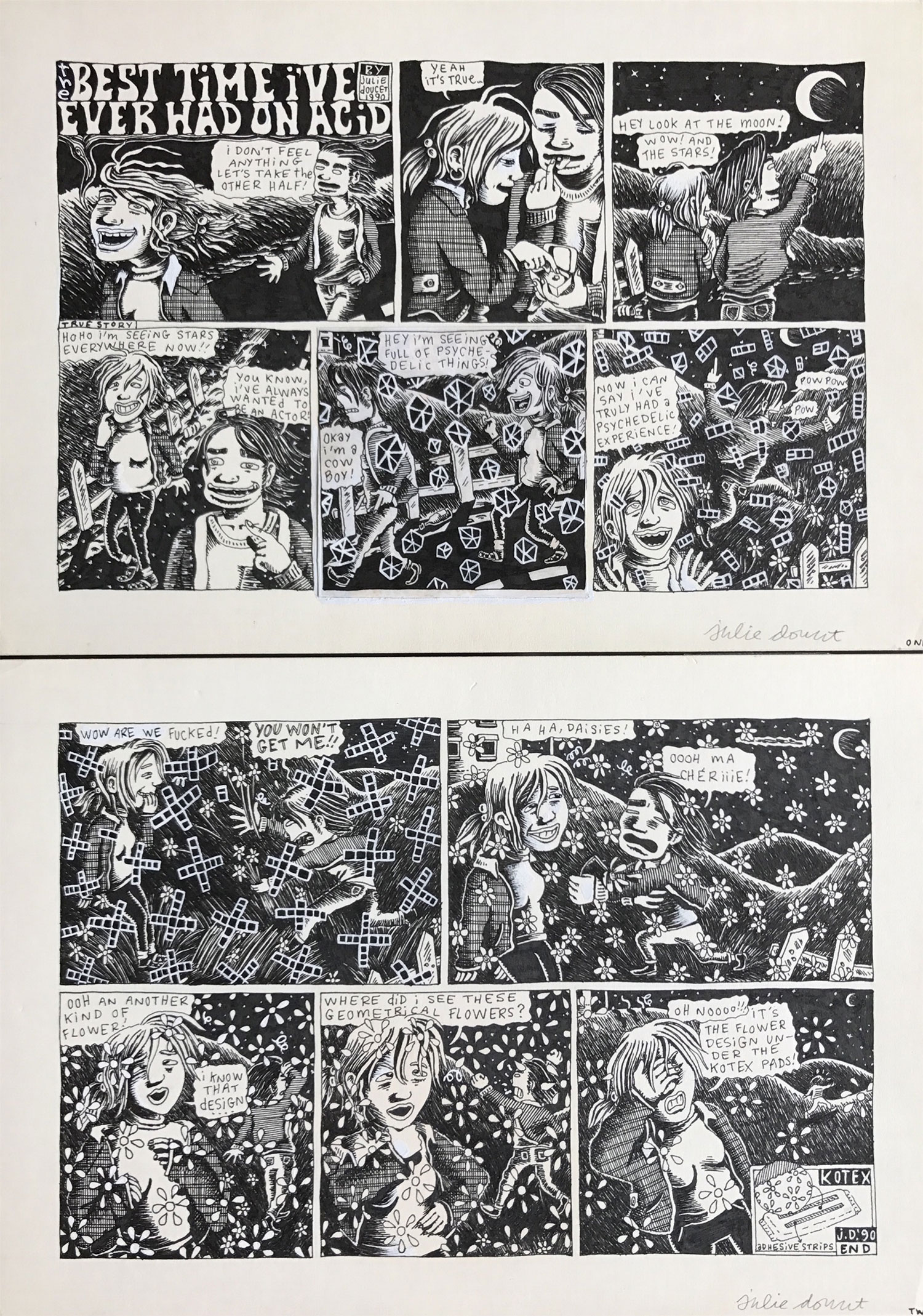

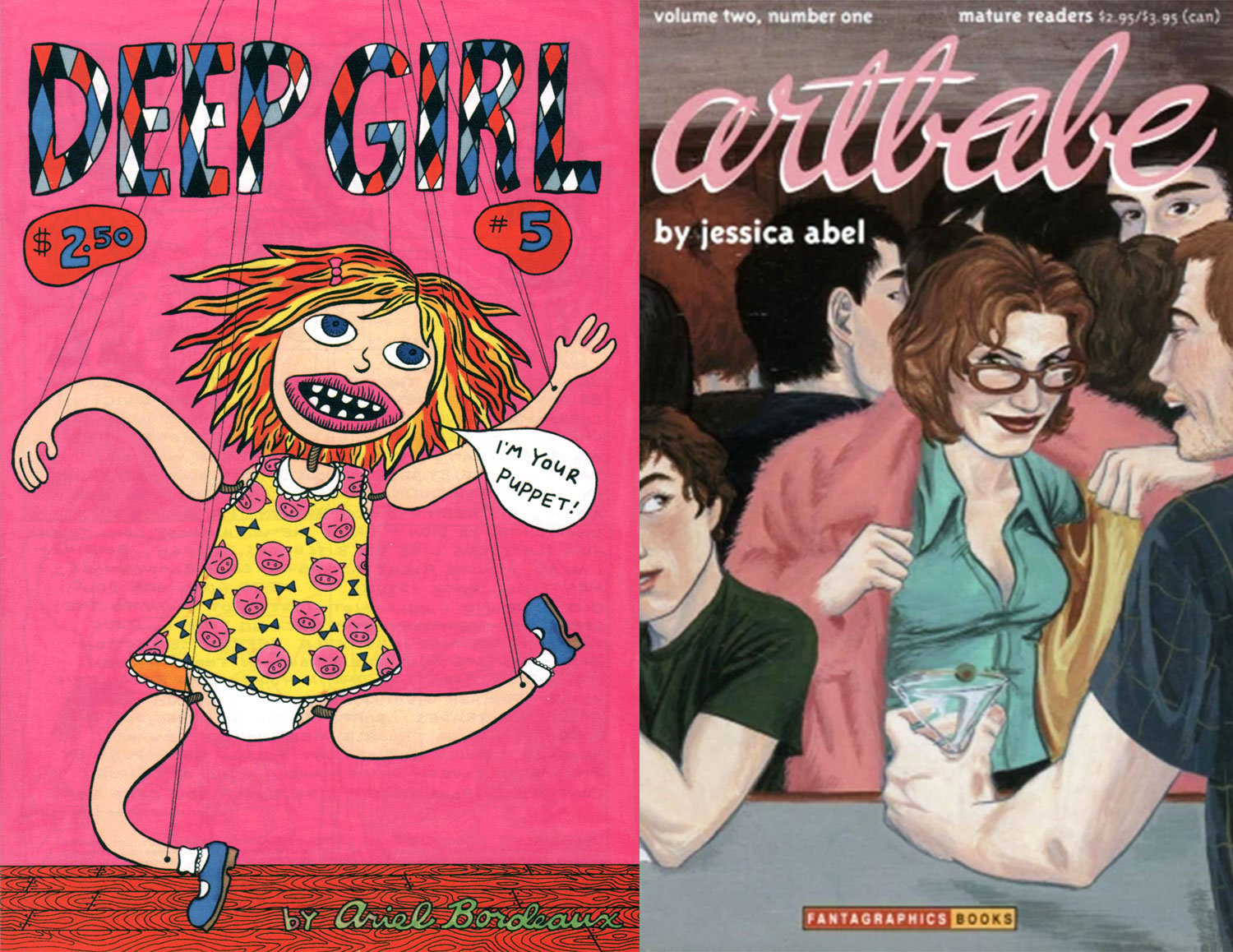

I have long believed that the cohort of female cartoonists that came out of the ’90s were the alt comics equivalent of riot grrrl. They were all responsible for pioneering mags and mini comics. Julie Doucet led the way in the late ’80s with the self-published version of Dirty Plotte, which was then published by Drawn & Quarterly from 1991 to 1998. Doucet’s comic was soon joined by Dame Darcy‘s Meat Cake (1993-2008), Ariel Bourdeaux’ Deep Girl (1993-1995) and Jessica Abel’s Art Babe (1992-1999), to name a few. Megan Kelso’s comic was called Girlhero and came out from 1991 to 1996. Those early stories are collected in the book Queen Of The Black Black, first published by Drawn & Quarterly and reissued by Fantagraphics.

Like riot grrrl bands, these women were creating art in a male-dominated environment. All of them embraced a DIY ethos and had a rebellious streak. They told stories from a female perspective in visceral and innovative styles that challenged the pristine production of most of their male counterparts. Megan actually started drawing comics while going to college in Olympia, Washington. I rest my case.

This interview was conducted in 2017, also known as a thousand years ago. Come to Lion’s Tooth on Tuesday, June 6 for a brand-new post-pandemic apocalypse conversation with Megan Kelso. The event window is 4-6 p.m. and the talk starts at 5 p.m.

Cris Siqueira: How did you get into comics?

Megan Kelso: I’ve always drawn, since I was a little kid. I liked to make up stories. I wasn’t putting them in the comics form. I wasn’t that interested in comics as a child. I read newspaper strips, but not much else. I didn’t think of comics as a way to express myself until I was in college. It was because of a boyfriend, a guy I met in college who was really, really into comics and he saw that I liked to draw and write. It seemed obvious to him that I should try comics. He showed me a lot of stuff, tried to get me interested in comics.

CS: Did he like alternative comics?

MK: He liked it all actually. He liked the alternative stuff but he also really liked superhero stuff and he showed me all kinds of stuff.

CS: Did you ever get into superhero comics?

MK: I tried because, at the time, I was so ignorant that they seemed more legit, in a way. It was also a time, in the late ’80s, when it was the beginning of superhero comics trying to tackle serious subjects. He showed me Watchmen.

CS: Which is good. It’s not a bad series.

MK: It’s okay, yes. I definitely had that stuff on my mind when I first started to draw comics. The more I got into it on my own, the more I realized that it didn’t fit where I was at. I was more drawn to the alternative stuff. Really, Julie Doucet was like the first cartoonist I saw that really struck a chord, like, “Wow, I would love to do be able to do something like that.”

CS: Her work stays with you. To this day, I can’t see a menstrual pad pattern without thinking of that acid trip story.

MK: Or floating her way to the bathroom when she’s got her period. I think about that every time I get my period. I wish I could levitate like Julie does. [laughs]

CS: What was it like to be a female cartoonist at that time?

MK: Well, at the time all the publishing opportunities went to men. That’s just how it was. One of the reasons that I called my comic book Girlhero wasn’t so much because I wanted to do superheroes, it was that feeling that I’d spent my whole life reading books, and watching movies, and humming along the songs from a male point of view, and having to do that little mental gymnastics where you still feel like you’re Holden Caulfield from The Catcher In The Rye. You’re still the protagonist and yet you’re putting yourself into a man’s body. We all know how to do that. We’ve done that our whole lives.

CS: So there was a feminist perspective.

MK: Yes. The idea of Girlhero was to make stories where the woman is the protagonist, and when a woman reads this they don’t have to do those mental gymnastics to identify with the protagonist. I was definitely coming into this world with a very clear feminist agenda, but to be honest, I thought of it all in terms of just, this is the work that I’m going to do. I’m not going to revolutionize the culture or the scene. My agenda was about the comics I was going to make, not about the surrounding art scene that those comics happened in. Looking back and seeing the advances that young women artists are making today, not just comics but in film and television and stuff, I do sometimes have pangs. Why wasn’t I able to extend my feminist agenda beyond the borders of my own work? But I also think that each era has its own battles. Hopefully, you can build on what came before but you can’t overturn everything at once. Then I try to give myself a break. [laughs]

CS: You were definitely a trailblazer.

MK: Well, often I remember being at comics shows and very friendly guys would come up and they would say something like, “Oh my god, my girlfriend is going to like this so much.” Which was a compliment but also felt like a diss, like, “Well, you know obviously, this isn’t for me, so,” but, “Oh, I know my girlfriend will really like this.” On the other hand, I always felt like the world of alternative comics was so small that if you were someone who was just a die-hard fan of the form, you would have to read the women as well, because there just wasn’t enough to read to keep you going unless you were willing to tackle it all. I feel like I got readers that probably would not have been attracted to my subject matter, but because they just loved alternative comics so much, they gave my work a try. I feel like that sort of male-dominated culture, it sort of went both ways in that regard. Comics were such a subculture, the readers were willing to read any subject that artists wanted to tackle, because they just loved reading comics.

CS: What was your relationship to other female cartoonists in the ’90s? I always think of you, Ariel Bourdeaux and Jessica Abel as a generation, the riot grrrls of comics.

MK: It’s intense. I started Girlhero and Ariel started Deep Girl and Jessica started Art Babe, but we didn’t know each other. There was this welling up of these ideas all over the place, and in a way, Ariel and Jessica and I were lucky that there was that connection. Because there was the sense of, “Wow, this is a thing that’s happening.” Not just in music but in comics. In a lot of ways it just had to do with what we named our comics, but it was more than that. We were all trying to get at some similar ideas in different ways.

CS: Are you in touch with them?

MK: Am I in touch? Well, social media, everybody’s in touch. Back then we all found each other through the mail. Adrian [Tomine] actually introduced me to Ariel through the mail. I got a comic from Ariel and she said, “My friend, Adrian, told me about your comics.” I can’t remember how I connected with Jessica, but again, it was somehow through the mail and then Ariel moved to Seattle, so I got to know Ariel quite well. We became quite good friends, in the years that we both were living in Seattle.

CS: Did you get support from older cartoonists, like Mary Fleener?

MK: Yes, again when I first started drawing comics, a lot of stuff was done through the mail. There was just sort of a protocol, almost. You would maybe send your mini-comic to someone you admired and very often you would hear back, get a little postcard or something. I remember sending stuff to Mary Fleener. I remember making contact with Trina Robbins. I remember them being very kind and encouraging.

CS: Shifting gears, can you talk about your creative process?

MK: Starting with “Cats In Service” [one of the stories in Who Will Make The Pancakes], I started working in a pretty different way than I used to, which involves a lot of extra drawing. I’m figuring out the story as I draw instead of writing a story and then drawing it.

CS: You don’t have a script? Risky.

MK: No script, no. I really just start drawing and then I figure out the story as I’m drawing. That entails a lot of drawing that you wouldn’t wind up using, like footage that you wouldn’t wind up using. Like, you can’t put every frame that you shoot into your film and I can’t put every panel that I draw into my comic. Luckily, I’m talking about really rough pencil drawings that aren’t that time-consuming. Then I did a lot of cutting them up and then reordering the panels and realizing I needed to draw some completely new stuff.

CS: What are your plans for the future?

MK: Well, I’m working on the book [Who Will Make The Pancakes]. I have stories that I want to tell. I do think they’ve been a little bit changed by the world that we’re in. Maybe not in an extreme way, but because I am a thinking person and I’m paying attention and I’m reading new stuff, I definitely think that things have shifted for me. I’m working on a story right now. It’s a story about sexual abuse but it’s not an extreme story. It’s more of the story that almost every woman has encountered and she wouldn’t necessarily think of herself as abused. Most of us have had some creepy gray area on most shit. That’s what it’s about. What am I trying to say?

I feel like those feelings and those experiences informed what I was doing 20 years ago but I couldn’t tackle it head-on. I feel like because of what’s happened in the culture, because of how feminism has moved, because of what younger women are doing, I feel like a permission of freedom to tackle this in a more direct way than I would have. To that extent, that’s the wonderful thing about youth. We had to be young once and break some barriers but it doesn’t end with us. They get to break more barriers and they make us feel like dinosaurs, but they also make the dinosaurs feel like they can try some new things.

Exclusive articles, podcasts, and more. Support Milwaukee Record on Patreon.

RELATED ARTICLES

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Eric Reynolds

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Peter Bagge

• 20 Years Later: Lion’s Tooth co-owner Cris Siqueira in conversation with Dame Darcy