Chicago’s Zelo Pro Wrestling has established a solid foothold in Milwaukee. The company will make its return to Turner Hall Ballroom on Sunday, February 27 for its “Level Up” show, featuring Zelo Pro champ GPA, Women’s champ Jordynne Grace, Laynie Luck, Oshkosh native Swoggle, and more. It’s no secret that Milwaukee has a rich pro wrestling history—we’ve talked about important WWE moments in Milwaukee before, and one only needs to turn their gaze toward South Milwaukee to the annual Crusherfest for a celebration of Milwaukee and Midwestern wrestling history. But the old school fans of The Crusher, or other classic larger-than-life icons like Hulk Hogan or Andre the Giant, would probably have loads to say about much of the Zelo Pro roster, which, compared to the 300-pound superhumans of yesterday, sometimes can look more like circus performers than wrestlers, what with their more slender builds and their occasionally flippy, high-flying hijinks.

Pro wrestling in the last 30 years certainly has begun to move away in part from swole, musclebound supermen (although guys like Brian Cage, Bobby Lashley, and of course, WWE Champ Brock Lesnar are certainly still attractions). One could point to a number of reasons for this: the steroid controversies of the 1990s (and the WWE’s subsequent emphasis on “smaller” talent like Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels), the ascent of MMA and the UFC (and with it, the realization among the general public that a 170-pound martial artist can be just as dangerous as any Charles Atlas type). But what we’re going to focus on today is the slow but steady ascent of high-flying, arial cruiserweight wrestling, a style that was an anomaly in ’80s/’90s pro wrestling, but began to gain a foothold in the industry thanks in part to a groundbreaking match that took place right here in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 30 years ago next week.

The night was February 29, 1992, and the show was WCW’s SuperBrawl II, live on pay-per-view from the building that we now know as the Miller High Life Theatre, but was then part of the MECCA complex. (Why the show wasn’t held in the MECCA Arena itself is a question whose answer is perhaps lost to history, although perhaps the crowd of 5,000 looked better on camera selling out the smaller theater as opposed to only half-filling the former home base of the Bucks.) Opening a show headlined by bodybuilding sensations Lex Luger and Sting was an opening match for the recently created WCW World Light Heavyweight Title, in which champion Jushin “Thunder” Liger defended his title against gravity-defying sensation “Flyin'” Brian Pillman.

In the early days of Ted Turner’s ownership of WCW, there was a lot of experimentation with importing talent from Tokyo-based New Japan Pro Wrestling, as well as a desire to find ways to differentiate the product from the juggernaut that was 1980s WWE (then the WWF). Enter Jushin Liger, an anime character come to life (no, really) who wrestled in a full body suit and mask that made him look like the offspring of Jet Jaguar and the Predator, and who also happened to be doing stuff off the top rope that no one had seen before. WCW brought him to the states, immediately booked him to beat WCW’s own high-flying sensation Pillman for their new junior championship, and set up a rematch in Milwaukee, a city that hadn’t exactly seen wrestling quite like this in person before. Pillman himself came into WCW with some hype as a Cincinnati kid who had a cup of coffee with his hometown Bengals before getting trained in Calgary in Stu Hart’s dungeon, so the stage was set for a match that was less babyface vs. heel than it was a match where two phenoms simply set out to one-up each other.

It’s definitely a match worth watching, if for no other reason than to see how the then-Milwaukee Theater was set up for a wrestling show. It’s kind of weird! A horizontal entrance ramp connects the stage to the ring, set up in the center of the theater floor and surrounded by a hot, rowdy crowd of certainly well-lubricated Brew City fans. The crowd goes nuts early when Jesse “The Body” Ventura is announced as one of the pay-per-view’s commentators, playing to the crowd by riding a Harley to ringside and referring to Milwaukee as “Crusher Country.” (Pairing him with announcing legend Jim Ross is an inspired choice.) The crowd is also hyped for a show featuring some familiar ex-WWF talent in “Ravishing” Rick Rude and Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat. Pillman/Liger is slotted into the curtain-jerker slot, kicking things off in the hopes of hyping up the crowd early with death-defying feats of danger. Who doesn’t love danger?

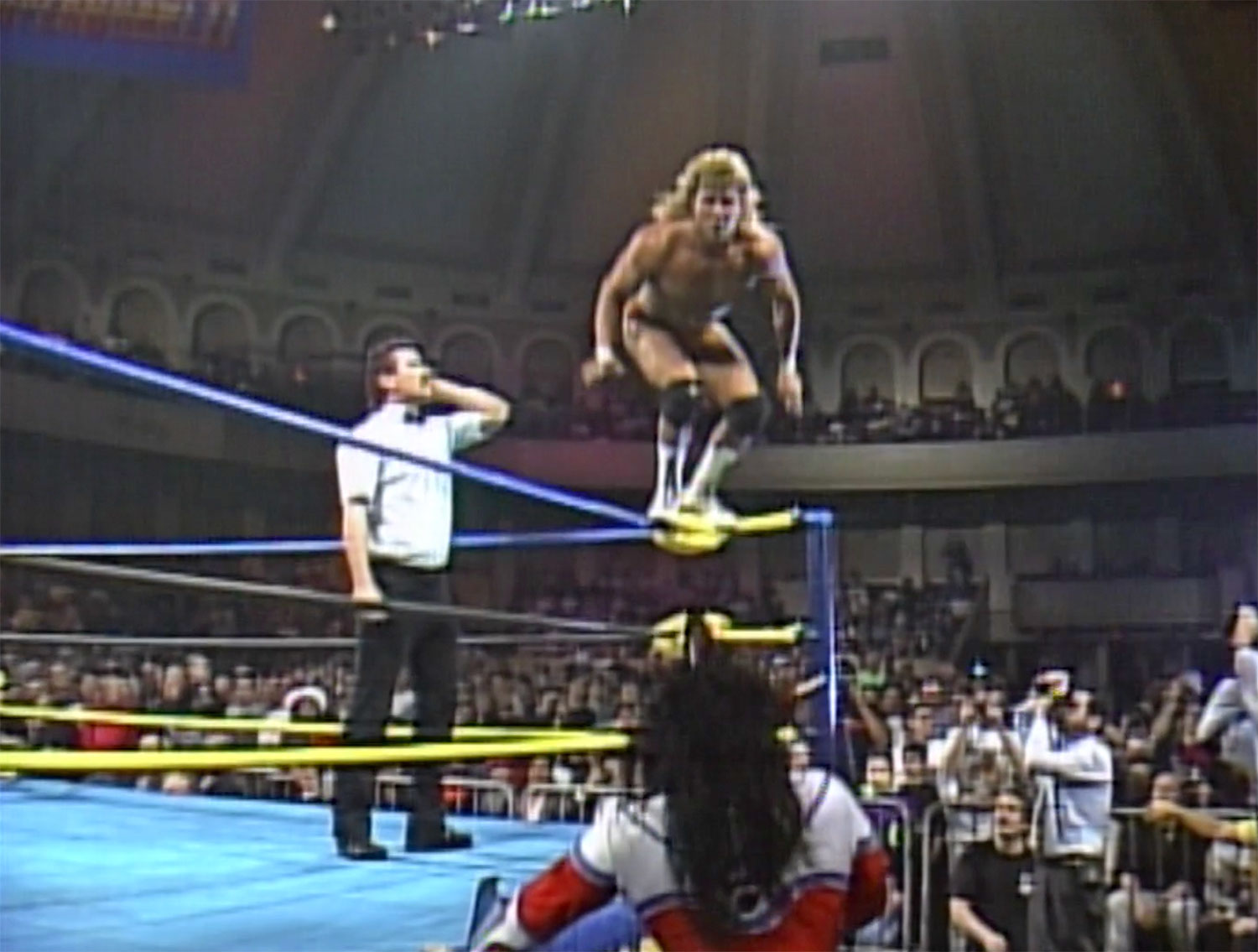

The story of the match is established early as Pillman tries to negate Liger’s arial attack by wrestling him on the mat, but an early sequence of moves ends with both men trying a dropkick at the same time and ending in a standoff. (Indeed, the match often features spots where the two men try the same risky move at the same time, with results varying from double-whiffage to cracking skulls in midair.) Liger actually out-wrestles Pillman early, locking in a figure-four and sending Pillman into the ropes to break the hold before his legs are rendered ineffective. Of course, this would be a boring match if Pillman’s legs were really hurt, so he guts through the damage to climb the ropes several times in the contest.

Wrestlers flying off the top rope wasn’t an uncommon occurrence in 1992—Randy Savage was hitting top rope elbow drops and axehandles against Ricky Steamboat back at WrestleMania III in ’87—but when Liger launches himself upside-down into Pillman’s face with a somersault senton off the top rope down to the arena floor, Jim Ross is so unfamiliar with the move that in his excitement he mislabels it a moonsault (a move Liger already hit earlier in the match). Come on, JR, get with it!

Eventually Pillman rallies and starts throwing his body at Liger, abandoning his original plan and connecting with a series of high cross-bodyblocks off the top. Like any good 20-minute PPV-quality bout, the action crescendoes to a fever pitch as both men eventually begin trading moves at a lightning-quick pace, thrilling the crowd with multiple leaps and near-falls. Liger eventually tries to one-up Pillman with a flying headbutt from the top, but when Pillman rolls out of the way, Liger crashes to the mat, giving Brian the opening he needs to roll Liger into a bridging cradle for the pin and the championship. Liger goaded Pillman into the air, but outwrestling Liger on the ground ended up winning the match after all! The Cincinnati native is awarded the title as the Milwaukee crowd celebrates, and Liger congratulates his conqueror as the two shake hands and hug in a rare display of sportsmanship in this era of North American wrestling.

It was a level of flippy grappling that many North American fans hadn’t seen yet in 1992, and while the rest of the show had plenty of entertaining moments (the Steamboat/Rude US Title match was a perfectly cromulent affair, with Ventura working in plenty more Milwaukee references throughout the show—including a distinctly heel remark about how “it’s not over until the fat lady sings, and if there’s one thing Milwaukee knows about, it’s fat women.” BOO, Jesse! BOOOOO!), the Light Heavyweight title tilt was by far the best match of the night. The Wrestling Observer’s Dave Meltzer gave the match a 4 ¾ star rating, which no other match on the show comes close to. In fact, it ended up being the second-highest rated match of the year for WCW. Surely, this kicked the door open for other smaller, more arial-based wrestlers to gain an audience in America, right?

Eh, not so much. Despite the enthusiastic reception for Pillman vs. Liger, WCW head booker Bill Watts, an old school Southern wrestling vet with a more conservative take on the good ol’ days of rasslin’, made the boneheaded decision to outlaw moves from the top rope in fall ’92, making most of Pillman and Liger’s offense grounds for disqualification in his new regime, and rendering the Light Heavyweight title useless. (The belt was eventually phased out that autumn, less than a year after it was introduced.) This move was seen by WCW fans as a generous load of crap, and when crowd response started to tank, the decision was reversed. But the damage had still been done, and WCW’s nascent cruiserweight scene was more or less put on ice until the company launched WCW Monday Nitro in 1995, and again looked for ways to differentiate the product from the WWF, recruiting even smaller workers, like the 5’6″, 150-pound Rey Mysterio.

Even then, the new WCW Cruiserweight Title, launched in 1996, didn’t really come into its own until Mysterio won it from Eddie Guerrero in a classic contest at Halloween Havoc ’97 that is held alongside the Pillman/Liger bout as a match that changed the game in pro wrestling. (WCW’s main-event roster remained the realm of giants who often punked out the cruiserweights for comic relief, including a classic moment where 6’10”, 320-pound Kevin Nash lawn darted Mysterio into the side of a production truck.)

The smaller flippy guys still have their share of detractors, but in 2022, wrestling fans accept them like they never have before. The downright normal-sized Darby Allin and Jungle Boy routinely headline episodes of AEW Dynamite and Rampage, and even Rey Mysterio ended up a multi-time world heavyweight champion in WWE. (We would be remiss if we didn’t mention the crazy acrobatics delivered to sold-out Turner Hall crowds by the Mondo Lucha roster once a year!) It can be reasonably argued that part of the groundwork for these wrestlers’ success and acceptance into pro wrestling’s mainstream was laid in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, just down the street from Turner Hall, almost thirty years ago.

Exclusive articles, podcasts, and more. Support Milwaukee Record on Patreon.

RELATED ARTICLES

• 6 behind the scenes stories from WWE Milwaukee

• If you go to WWE Smackdown at the Bradley Center, don’t flip off the talent: A cautionary tale

• Since Road To WrestleMania is canceled, enjoy some of WWE’s best Milwaukee matches