Dan Shafer is the founder of The Recombobulation Area, an award-winning, reader-supported weekly column and online publication. Click HERE to subscribe.

It’s the Local Debate Topic du jour. When we’re not arguing about the streetcar for the 800 gajillionth time, the hot new discussion is the proposed removal of the lakefront spur of this freeway, between the Hoan Bridge and the Marquette Interchange. One way or another, Milwaukee’s insatiable lust to have grating conversations about complicated downtown infrastructure projects must be satisfied.

It is kind of a confusing potential project, though, since most people associate 794 with the Hoan Bridge. But the Hoan Bridge is not part of the proposed teardown. I repeat: The Hoan Bridge is not part of the push to tear down 794. But that confusion only adds to the ubiquity of the argument.

This topic is a timely one this week, as well. The deadline for public comment on this project is Friday, September 1. If you, loyal Milwaukee Record and Recombobulation Area reader, have things to say, it’s last call over at the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT)’s online public comment form, so get on over there and have your say. Participation is power.

REMINDER: You have until the end of this week to provide feedback on the Lake Interchange Study. These comments will help shape the future of the corridor. You can find a comment form here ➡️ https://t.co/8HrNxrqxwg pic.twitter.com/QoVaaB36OW

— WisDOT Southeast Region (@WisDOTsoutheast) August 28, 2023

WisDOT is listening to feedback more than they have in the past over there, multiple sources say. What’s said on these forms is part of public record. What’s said in various comments sections or on X, formerly known as Twitter, is not. WisDOT has previously cited the percentage of public comments on a certain side of the issue in making a decision—and lobbyists will often flood these comment pages by engaging with their members—so you making your voice heard here is incredibly important.

Here’s that link directly to the comment page, once again.

Truthfully, though, this isn’t even the most interesting freeway removal proposal being discussed in Milwaukee right now. That honor belongs to the Stadium Freeway, a potential highway-to-boulevard project that is currently being studied by WisDOT. It has support from leaders at the city, county, and state level, and it would go much further to address core underlying issues of segregation and underinvestment in diverse neighborhoods that are plaguing Milwaukee.

It’s not lost on me that a recent public involvement meeting on the Stadium Freeway got sparse media coverage while the 794 hearings blanketed the local market and drew hundreds of attendees. Things happening east of I-43 in this town sure do seem to get more attention. Wonder why that might be! It even seems like the 794 debate is getting more attention than the billion-dollar I-94 East-West widening and expansion mega-project that continues to move forward. But you’ve already heard a whole lot from me on I-94 and the Stadium Freeway—and you’ll certainly be hearing more once designs for a reimagined 175 are unveiled (as soon as this fall, perhaps?). But at the moment, the matter at hand is 794.

Why now? Well, in late 2021, WisDOT proposed a $300 million reconstruction and replacement of many of the ramps and bridges connecting 794 to the Hoan Bridge. Kevin Muhs, city engineer in Milwaukee, explained to me why this all came about as part of this “Lakefront Interchange Study.”

“Basically,” he said, “between the (Milwaukee) River and the Hoan (Bridge), some of the bridges, ramps and mainline have not been redone since they were originally constructed, and that is the impetus for all the work WisDOT is doing. They do need to replace parts of the mainline and the ramps because they are nearing the end of their useful life.”

So, with that bridge and ramp replacement proposal from WisDOT—which, it should be noted, is a dollar figure more than double the cost of the streetcar system with the lakefront line, characterized for decades as the greatest boondoggle in the history of time—that opened the door for some to think differently about how best to approach a reconstruction project on this very valuable piece of land.

Enter 1000 Friends of Wisconsin, a transit advocacy and environmental protection organization that has been heavily involved in the opposition to the expansion of I-94 (they put forth the “Fix at Six” plan). Last year, they introduced the “Rethink 794” proposal, with splashy renderings and big, creative ideas for ways to remove the lake spur of the freeway, reconnect disconnected neighborhoods, open up space for new development on some of the most valuable real estate in the state of Wisconsin, and make it much safer to bike and walk in these neighborhoods.

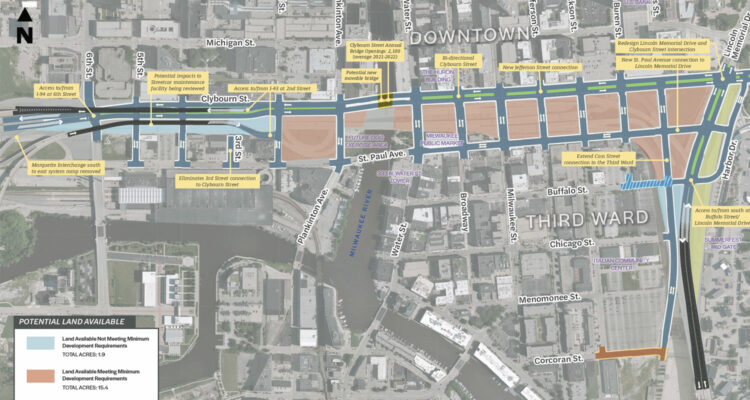

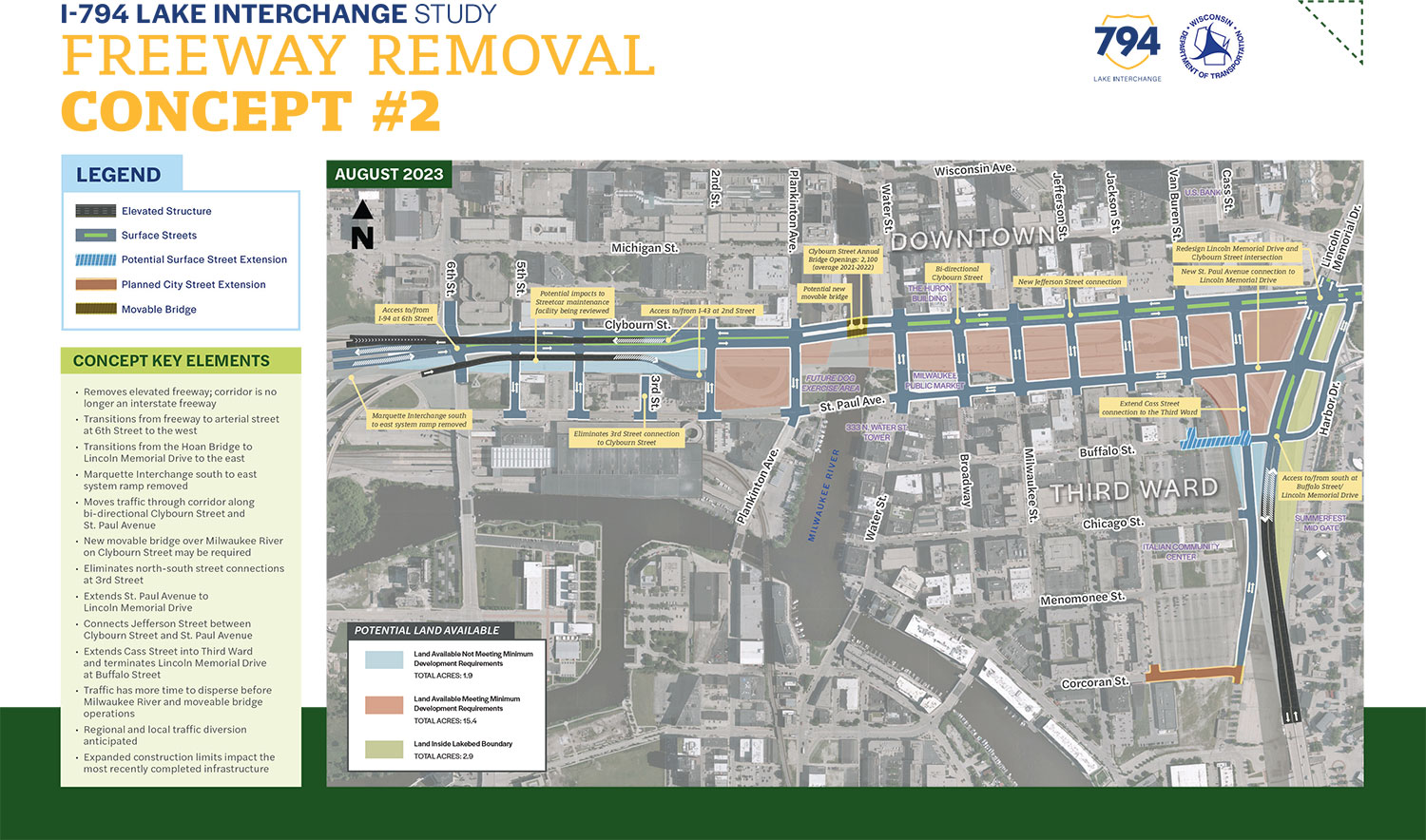

The idea gained traction, and less than a year later, two “Freeway Removal Concept” options were included in the Lakefront Interchange Study, put forth at two public involvement meetings in Milwaukee, which drew more than 700 people to attend.

“We support the removal of 794,” said Carl Glasemeyer, transportation policy analyst at 1000 Friends of Wisconsin, who specifically identified “Concept #2” among WisDOT’s publicly presented options as the one the group favors. “(We support this option) so that we can see all of the opportunities that open up for reconnecting the downtown of Milwaukee,” including parts of the central business district, the Third Ward, Westown, Walker’s Point, the Intermodal Station, and “making better connections from the river to the lake.” That favored concept removes the freeway all the way to 6th Street, and would remove the largest amount of the freeway of any option presented.

Those options presented by WisDOT include everything from a “Replace in Kind” concept to six different “Freeway Improvement Concept” options to two “Freeway Removal Concept” options. They represent a spectrum of what’s being considered, including various versions of more slimmed down replacements, where the elevated freeway connection between the Hoan and the Marquette Interchange is maintained, but with fewer connected ramps and a smaller overall footprint.

A few of these concepts will essentially be voted off the island as the process unfolds, perhaps in the not-too-distant future. While the decision over what is eliminated and what advances will ultimately be a decision made by WisDOT, the City of Milwaukee wants to see at least one of the removal concepts advance to be studied more thoroughly.

“Our main perspective at this point is that a full removal alternative does need to make it to the next stage and be fully vetted and considered as part of that stage,” said Muhs.

Lafayette Crump, the commissioner of the Department of City Development, said freeway removal or a “significant reduction to the freeway footprint” would be #1 and #1a on the City of Milwaukee’s list of preferred options for 794.

“The idea of a removal of that section of highway is very attractive, certainly,” he said, adding that there are a number of other methods for people to get to and through downtown if this spur were to be removed. “And so we look at what that would mean if it were to be removed. It would…open up quite a bit of land, it has the potential to facilitate greater connection between downtown and the Third Ward, make the area more walkable, and create more public space.”

While Crump said there are many issues he and the city would like to be properly studied as part of a full removal if that option advances in WisDOT’s process—what is not preferred at the moment is a continuation of the status quo.

“Frankly, we don’t want any kind of ‘replacement in kind,'” he said. “We want a better replacement than what exists at the moment.”

To be sure, there are concerns with a full removal that would need to be properly evaluated, Crump said—namely, access to the Port of Milwaukee, impacts on city streets, and building new bridges over the Milwaukee River. What’s not as concerning, he said, is saving a few minutes of commute time.

“All of those other things are real issues that have to be studied to avoid unintended consequences,” he said. “Now, people have talked about commute time increasing by 10% to 20% because you lose the speed on the freeway. That is a concern that we’re cognizant of, but we all know that Milwaukee as a metro area has some of the lowest commute times in the nation…So we do not believe that adding just a hair to those commute times is a significant concern, but nonetheless, we want that to be a part of the evaluation as well.”

A point Crump referenced several times in our interview is the new Downtown Area Plan, recently passed by the Common Council and signed by Mayor Cavalier Johnson, which advocates for reimagining the 794 corridor. This much is clear: The city is very much on board with change at 794—and change, in general.

The conversation about removing or replacing 794 might have as much symbolic meaning as logistical one, considering the spotlight it’s under. There are projects of greater importance within the city, to be sure. Addressing safety issues on streets like Capitol Drive, recently named the city’s most dangerous street, is a higher priority. Reworking the clusterfuck of an intersection of 27th Street, Center Street, and Fond du Lac Avenue is of greater importance. There are bigger fish to fry than 794.

But under Mayor Johnson’s leadership, the city of Milwaukee is taking a different approach toward its built environment, with an urbanist vision and a goal to grow. This debate over the future of 794 is an inflection point for the city. How do we want to build this city for its next generation? Are we going to keep prioritizing quick vehicle access in and out of downtown, or actually start building streets for people?

In a way, we already have our answer. Freeway removal is an issue on which Milwaukee is actually ahead of the curve. We’ve done this before. We can do it again.

“Milwaukee is at the forefront of replacing freeways,” said Peter Park, the former city planner at the city of Milwaukee, who championed the removal of the Park East Freeway, at a recent conference and panel discussion on I-794 and downtown at Marquette University. “This is not a new thing for Milwaukee. Milwaukee started a trend that is influencing how urbanists, how city leaders and how even our federal DOT is thinking.”

It’s a reminder that we don’t have to look far to see a successful example of downtown freeway removal leading to a development boom. The removal of the Park East Freeway led to the eventual construction of Fiserv Forum and the Deer District, as well as a host of developments in nearby neighborhoods. Bob Monnat, senior partner at the Mandel Group, even said during that panel discussion of one of their more successful developments, “The North End may not have ever happened with the Park East Freeway up.”

“The City of Milwaukee has been great at compromising,” developer Tim Gokhman said at that panel discussion. “And good enough is not good enough.”

So we know freeway removal can work, we know it can work here, and we know Milwaukee can lead the way.

Some might scoff at the type of development this might invite, with the type of trendy “luxury apartment” vibe that’s happening all over downtown and is immensely easy to ridicule. But that type of development creates a huge amount of property tax revenue, and Milwaukee as a city is more reliant on property tax revenue to fund its budget than any other revenue source (and that’ll be true even when the sales tax kicks in), so those types of developments end up going to fund libraries and the health department and public safety and snow removal and trash pickup and all the other things that make the city tick.

So, TL;DR: Because of how reliant we are on property taxes, development anywhere helps Milwaukee everywhere.

The city recognizes this connection, too. “This is also—to be as candid and real about this as possible—this is also a strong commercial development play,” said Crump. “We need to increase our tax base and this is an incredible opportunity to have more land available that increases the tax base, adds population to the city, creates more space for more of the kinds of incredible development we’ve seen in the city. So, residential, office, hotel are all strong components for what we would (like to) see in that area.”

And if the city is serious about this urbanist vision being put forth by Mayor Johnson—and I genuinely think they are—there are ways to be proactive about the new space to augment and improve the overall development: building connections with parks or transit; incentivizing affordable housing; creating new bike lanes and walking paths; etc. There are a lot of potential options to consider—certainly moreso than figuring out which freeway onramp could fit a parking lot under it and hoping people don’t get run over because there’s nowhere to walk.

One important piece to this that people I’ve been talking to and interviewing on this subject continue to reiterate: Leaders are listening on this issue in ways they hadn’t before. The urbanist crowd might be loud on Twitter (guilty), but they’re also showing up to public meetings and contacting their representatives and getting into the weeds to do the work. That stuff matters.

“I think a piece that cannot be understated is public pressure from the kind of urbanists that are out there, not just shouting into what some call the void on social media, but truly putting together their own preliminary analyses and talking about these issues,” said Crump. “And so there’s been pressure on the city and on WisDOT to do a real evaluation here.”

The next part of the process needs to include a real evaluation of a freeway removal option for 794. WisDOT needs to do its part, for once, and recognize Milwaukee’s needs and vision in ways they did not throughout their decision-making on the I-94 East-West corridor.

There is opposition to a freeway removal option, particularly from a number of south side suburbs. Republican State Sen. Duey Stroebel also voiced opposition to change. There is some simmering trepidation about freeway removal from downtown businesses, particularly at the C-suite level, even if they’re not being vocal about it. And outside of developers, downtown businesses, organizations and entertainment groups have not shown public support for change.

But in seeking change, Milwaukee can both draw on its history as a freeway removal pioneer and stay ahead of the curve in building its urbanist vision for the future.

Highways are best used going to a city, not through a city. Blasting lanes and lanes of concrete through dense neighborhoods does not improve the city. Period.

I recently posted a Twitter thread about a drive through Minocqua, and reaching a slowdown in traffic. Should we build a massive freeway through its downtown, residents and businesses and preservation of a charming downtown be damned? Obviously not. But this is the same logic that those wanting to keep the status quo are bringing to the 794 debate.

On our trip Up North this weekend, I drove through Minocqua, a place I've always enjoyed. But we ran into some traffic driving through. Slowed to a stop. And I know this might impact people and businesses, but we should really expand the highway there to eliminate any congestion.

— Dan Shafer (@DanRShafer) August 1, 2023

The best option on the board right now for 794 – with hundreds of millions of dollars in ramp replacement likely going forward regardless—is to choose a new path at this fork in the road. It’s time to give Milwaukee the chance to do something new. It’s time to tear down 794.

Now, go fill this out and tell them what you want the future of your city to be.

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation did not respond to a request for an interview for this story.