The message from my wife popped into my inbox during work a few weeks back. “We just got a mysterious wrestling VHS tape from [her co-worker and our friend] Eric! He says it’s the MWA?”

We immediately agreed that he must have misread. He must have meant the NWA, right? Who’s ever heard of an MWA? Obviously this was a bootleg tape of some old Mid-South or Mid-Atlantic Jim Crockett stuff or something. The tape itself offered no clues—there was no label whatsoever, and the sleeve was plain white. (If you looked closely at the spine you could see the word “wrestling” indented, like the ghost of a long-gone label.) And it was handed off to us simply because Eric knew that we’re into wrestling, he had it in his possession for who knows how long (he told my wife he got it at an estate sale or something—who knows), and he thought we’d get a kick out of it. But what the hell was the MWA? Like we said earlier, that had to be a mistake. We were going to pop this in and find some lost Magnum T.A. classic, certainly.

That night, we fired up our VHS player (stacked between our Blu-ray player and our double-cassette deck, as one does when putting together a state-of-the-art entertainment system), and hit play.

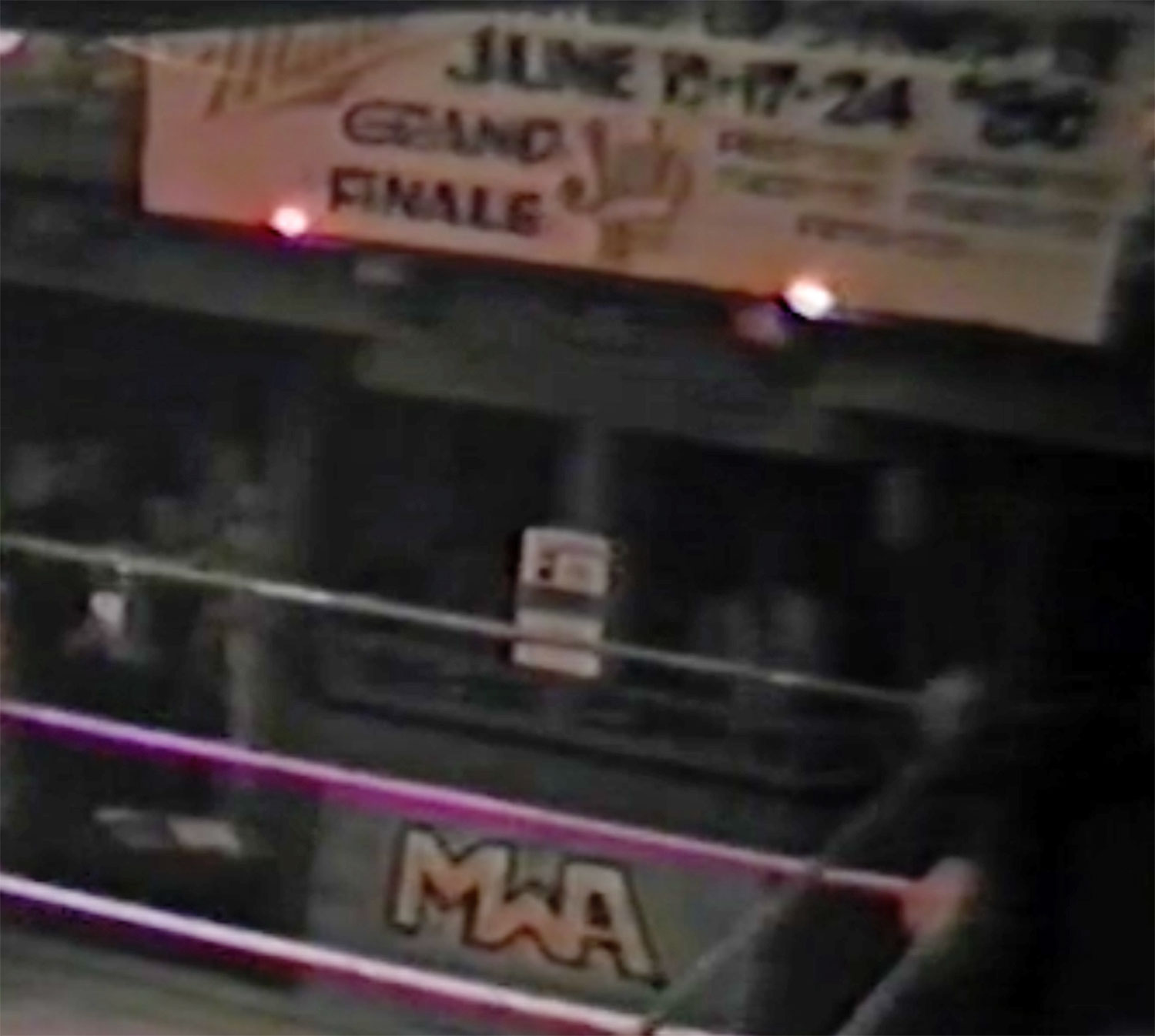

It wasn’t a mistake. As the tracking buzzed into place, a spartan, white wrestling ring popped into view, with the letters “MWA” clearly emblazoned on the mat in basic, plain blue text. A mustachioed, tuxedo-clad ring announcer read from a clipboard while two unnamed professional wrestlers, one of them completely jacked to the gills, paced the ring. I say they were unnamed because the video had no title graphics and, weirdly, no sound. Why the hell does this video have no sound? Who are these guys? Where was this taking place?

The show seemed to be held in a bar, or a tiny VFW hall. Dimly lit fans sat right up against the ring, which took up almost the entire continuous, single-camera shot. At some point, the camera moved enough to reveal a banner above the ring advertising the mystery venue’s lip-sync contest finals, happening June 10, 17, and 24, in the year of our Lord 1986 (this completely tracks, as lip-sync was all the rage in the decade of Star Search with Ed McMahon). Eventually a wrestler dressed up as a Sheik entered the ring, complete with a rug with which to bow toward Mecca. Was he actually facing East? Difficult to say, but I’m guessing not. He didn’t look Middle Eastern, that was for sure, but that didn’t exactly stop pro wrestlers in the 1980s. Hell, most of that decade’s ‘Russian” villains were from Minnesota. Whoever he was, he was apparently in the main event, as his opponent wore a shiny slab of tin around his waist. The MWA Champion, I suppose!

My wife and I were gripped by this tape. Blank label. No sound. Hell, it even appeared to be dubbed over someone’s old little league baseball game, to really up the randomness. Where did this come from? Was this local? What the hell did the “M” in “MWA” stand for, anyway? Milwaukee? Midwest? Missouri? Minnesota? Certainly not Michigan—if the Original Sheik, Lansing native Ed Farhat, saw this other guy pinching his gimmick, there would have been a ruckus. This was like stumbling across an unlabeled record from a mysterious, no-name local band from another era and finding out that it fucking rips. We had to learn more.

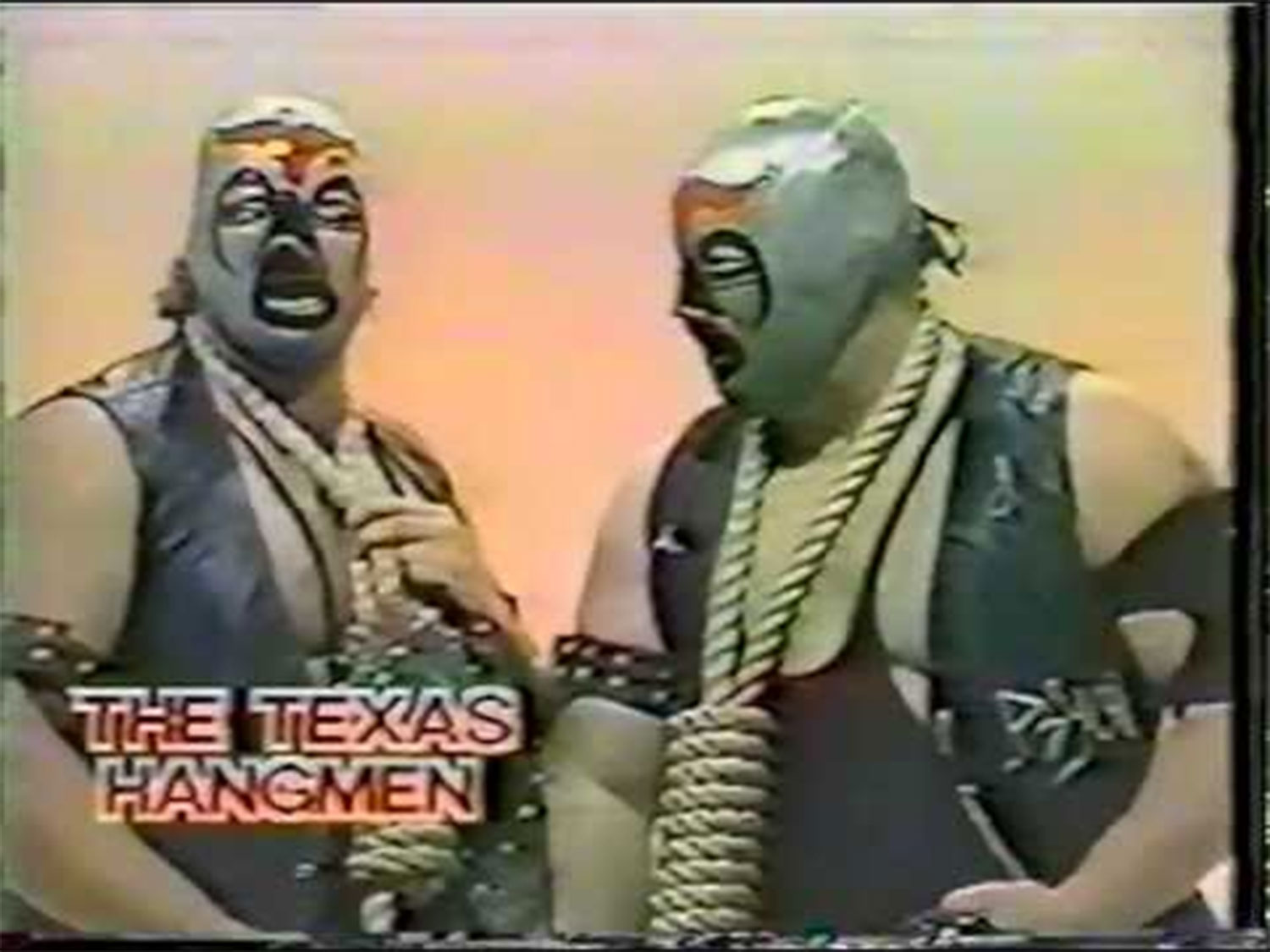

It was time to call in some reinforcements to see if we could solve the mystery of the soundless indie wrestling tape. I sent a message with some screen shots to my close personal friend Daryck St. Holmes, Esq.—local wrestler, historian, and my broadcast commentary partner in Mondo Lucha’s DVD enterprise—to see if he had ever heard of this mystery promotion. He had not—but he had some friends who had, and he was happy to put me in touch with them. Before too much longer, Daryck had looped me into a conversation with Tom “Rocky” Stone and one half of the notorious AWA tag team the Texas Hangmen.

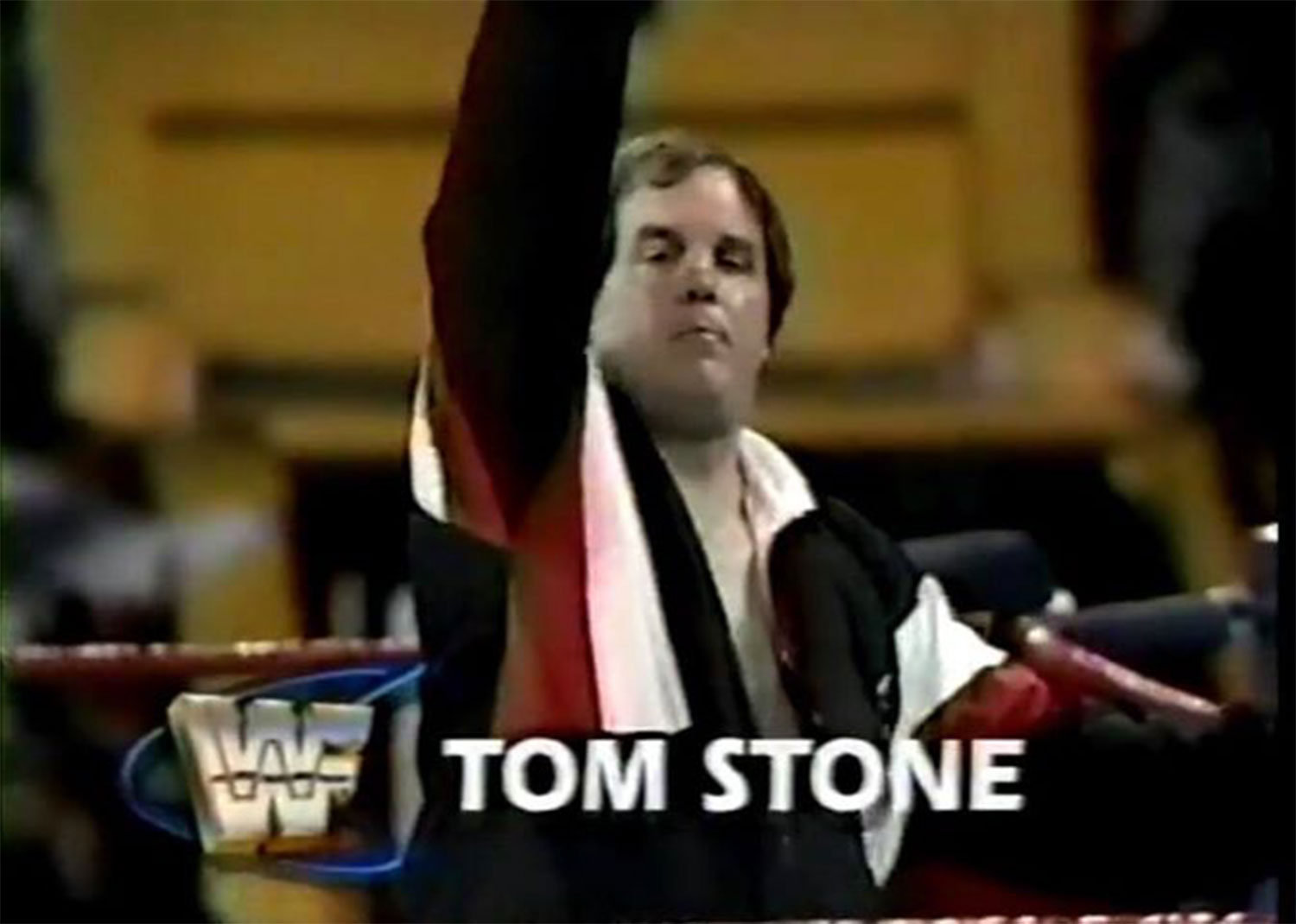

Tom “Rocky” Stone was a Milwaukee-based jobber, working TV tapings for the WWF and AWA in the 1980s. In pro wrestling parlance, a “jobber” is a lower-tier wrestler that “does the job” for the more established stars higher up the card. In other words, the “job” is to let the stars kick the shit out of them, making them look like, well, stars.

Tom Stone existed on the same level as Barry Horowitz, Reno Riggins, or “Iron” Mike Sharpe—guys I regularly saw getting their asses handed to them by “Ravishing” Rick Rude or The Honky Tonk Man on WWF Superstars Of Wrestling. But when he wasn’t on TV, Stone was one of the central figures of Milwaukee independent wrestling, booking local shows and using his worldly wrestling experience to train many of the local wrestlers of the day, including an AWA jobber named Mike Richards, the man who eventually became “Killer,” one of The Texas Hangmen, and the second man Daryck introduced me to. Mike Richards also happened to work under a third name: Mike Madigan, who, as it turns out, was the MWA Champion featured in our mystery video tape. (The guys in the first match? Chris Curtis and Lance Atlas. I’m guessing Atlas was the super-jacked dude. Dynamic TensionTM, baby!)

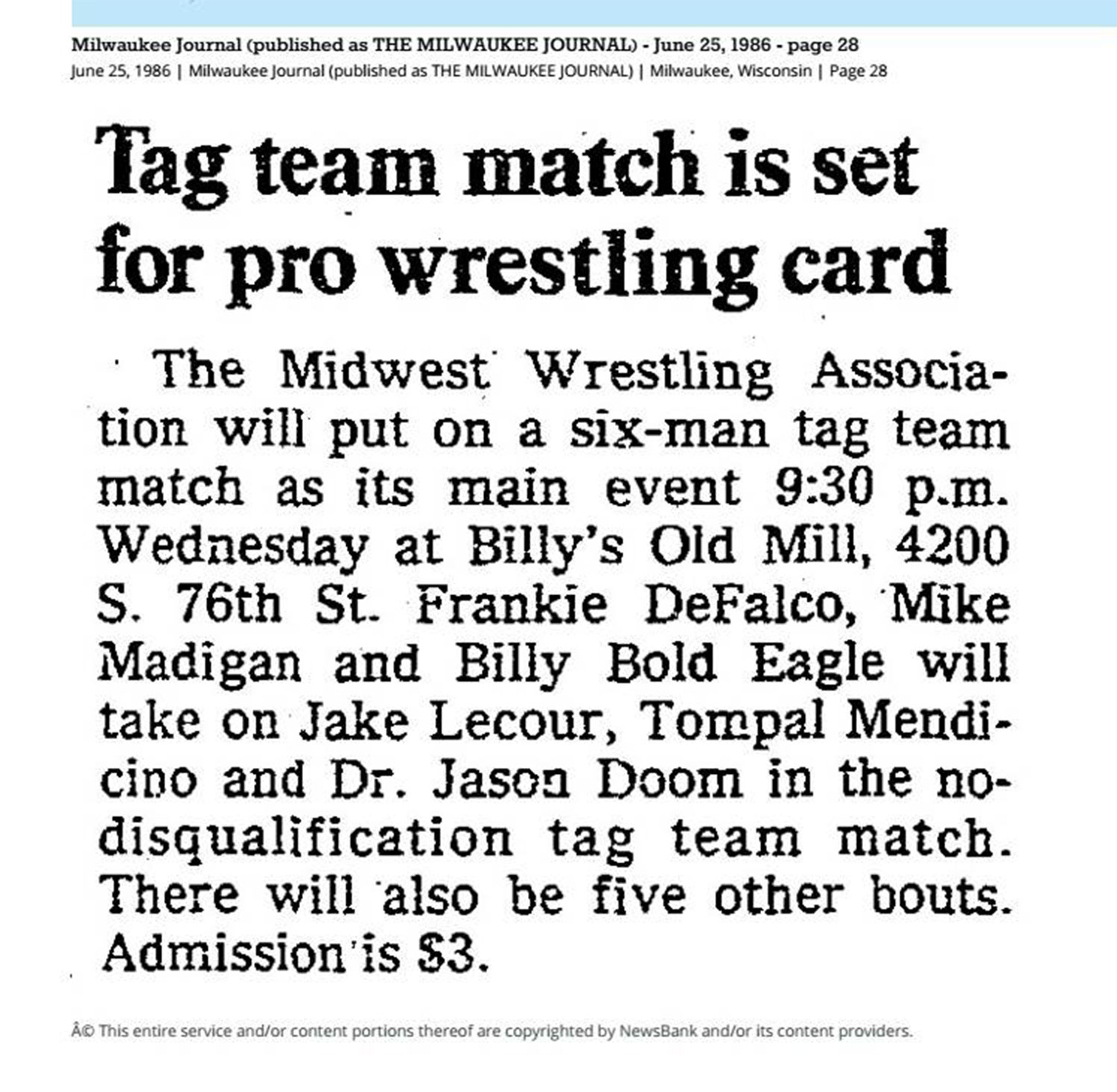

Stone clarified for Daryck and me that “MWA” stood for “Midwest Wrestling Association.” The promotion, such as it was, was bankrolled by Dale “Rev” Prochnow, a local promoter of monster trucks and Jell-O or mud wrestling, and the ring announcer in our mystery video. The shows traveled a circuit around various Milwaukee bars, halls, and bowling alleys, the centerpiece being Federation Hall on 13th and Lincoln. The show in the video? Red Carpet Lanes/Rooters in Waukesha.

“They ran at Billy’s Old Mill in Milwaukee,” Hangman told me. “Zivkos in Hatford. Wylers in Port Washington. Vance’s in Racine. Those were the four I recall that were somewhat regular, as well as Red Carpet in Waukesha. Rev would also book random high schools and fairs in the summer.”

Courtesy of History Of Rasslin In Wisconsin

According to Stone, Prochnow would secure the money from the venue, give Stone a budget, and let him book the talent. Stone would end up putting together lineups full of local workers that he would also occasionally send to the AWA or take along to a WWF taping if he thought they were good enough for TV. Since Stone was training lots of these guys, too, he had a good handle on who he thought was worthy of a push to the “big time”—getting beaten up on TV.

But make no mistake: According to Hangman, if you were wrestling for the MWA, you weren’t exactly doing it for the money or any promise of eventual fame.

Hangman gave me as much background as he could recall about his time in the Midwest Wrestling Association. It was early in his career; his pro debut as Mike Madigan was in 1982, and he estimated that the MWA existed for a blip on the cosmic calendar, from ’85-’87.

To hear Hangman and Stone tell it, the MWA was one of a number of wrestling “feds” in the area—a real “alphabet soup” of promotions, in Daryck’s words. Three-letter names would come and go based on who was writing the checks, but with Milwaukee being a smaller, close-knit scene, it was usually the same talent on the various shows, with a lot of the same 200 or so fans filling up the bars. In fact, once local wrestler, Trevor Adonis, bought his own belt and started IAW—the International Alliance of Wrestling. Both Stone and Hangman agreed that was around the time the “MWA” letters stopped being used.

Still, no matter who was bankrolling at any given time, there was a solid loop of bars and some loyal fans hitting all the shows to keep things relatively viable. Not, like, overly profitable, but viable. Hangman remarked that at many shows the talent would be lucky to get $25 apiece, but they weren’t doing these shows for the money—this was strictly a “love of the game” scenario. Any money these guys were making was getting doled out by whatever companies let them do jobs on TV, were they lucky enough to get those gigs. And fame? Well, fame was hard to come by when you were required to change your name to work the local shows.

That’s right: MWA Champion Mike Madigan was required to be Mike Richards when working for Verne Gagne’s AWA. Another local worker who went by Jake LaCour became better known on AWA television as Jake “The Milkman” Milliman. (Google “AWA Team Challenge Series” to learn about ol’ Jake’s bizarre claim to fame in the rasslin’ biz). According to Hangman, if Gagne found out that his jobbers were being presented as legitimate talent elsewhere, they’d be fired, so they all worked under different names on the local shows. God forbid that anyone find out that MWA champ Mike Madigan was the same guy getting squashed by Jerry “Crusher” Blackwell on AWA TV! (Of course, the so-called “Sheik” on the video tape ended up being another notable and distinctly non-Middle Eastern jobber named Pete Sanchez, who appeared on the Saturday morning WWF shows a lot.)

By the time the MWA was about to morph into IAW, Mike Madigan was ready to move on up. Having done solid work for the AWA in his jobber role, Gagne wanted to give him a bigger push, but back then, jobbers didn’t really move up the ladder, as promoters didn’t see it as very credible. (“That guy lost to Blackwell last month, and he’s beating Jim Brunzell now? This shit has to be rigged.”) To work around this, Gagne teamed Madigan with another jobber, Rick Gantner, and put them both under masks as a mysterious heel tag team. And thus, The Texas Hangmen were born.

The gimmick had legs, eventually taking the renamed “Killer” and “Psycho” to Puerto Rico, where they were involved in a fairly profitable storyline with Invader I (a.k.a. the guy who stabbed Bruiser Brody in the shower, but that’s another story). Madigan even eventually had a brief run with another partner in WCW as the team Disorderly Conduct before returning to the indies and eventually retiring in 2012.

But the MWA was one of the places where Hangman/Madigan got his start, and for this, he gives heaps of credit to Tom Stone, his trainer and, in Hangman’s words, “the godfather of Wisconsin pro wrestling.” When talking to Stone, it was clear that he took a lot of pride in the way he trained nearly every key player in the Milwaukee wrestling scene of the time. After starting his career in ’78 and ’79 in Wisconsin, Stone spent about a year in the Mid-South territory, which promoted out of Oklahoma and a few surrounding states, learning what he referred to as “the theory of wrestling.”

“When I came back to Wisconsin, I taught guys the theory of wrestling—how to actually put a match together, not just how to do the moves,” Stone told me. When I asked if that was part of why he was able to get Milwaukee guys booked for TV, he seemed to agree. “We produced the best jobbers in the country right here in Milwaukee.” (Stone tells a lot more tales from his career, including more Milwaukee stories, in his book, Professional Wrestling – The Theatre Of The Absurd: I Never Wanted To Be A Big Star, in stock at Amazon!)

As I absorbed the stories from Stone and the Hangman, it occurred to me that they were reinforcing something I have long held as true: local pro wrestling is a lot like the local music scene. Both are full of talented folks participating in a subculture for, hopefully, the pure love of it. A band getting $100 out of the door on a good night isn’t much different than a local pro wrestler getting paid $25, a hot dog, and a handshake. As Hangman himself said, “I probably wrestled in front of, I’d say my biggest crowd was around 20,000, but I gave just as much effort in front of 200.”

And isn’t that a quality of some of the best local musicians you see on any given night across town? Local musicians who put in time on local stages not for a shot at the big time, but for the love of the craft, and who occasionally might get a shot on an opening bill for a bigger act, not unlike the jobbers who get to support the bigger stars by making them look good. And both professions have to deal with confused outsiders wondering how long it will take them to quit once they realize they’re not going to “make it.”

I should point out here that we’ve been talking about “jobbers” a lot in this piece. The term “jobber” tends to be used derisively in the fantasy world of pro wrestling storylines—after all, a guy who gets his ass kicked on the regular can’t be very good, right? But in pro wrestling, where the matches are scripted, that’s never necessarily the case. It’s the jobber’s role to make the star look good, and in a scripted sport with choreographed move sets, a jobber needs to know what they’re doing in order to make the star look like, well, a star. Not every top-shelf WWE superstar is necessarily a good wrestler, per se—the less said about The Ultimate Warrior, the better—but the jobber that makes The Ultimate Warrior look like a godlike streak of pure energy absolutely has to be. That jobber better know some moves, and they better know the “theory,” as Tom Stone put it.

And yeah, I agree with the use of that word. There’s music theory, and there’s wrestling theory. Stone broke it down for me on the phone—there’s a formula that basically every wrestling match adheres to. There’s an opening period where the babyface gets his shine by hitting big moves early to excite the crowd. Eventually the heel takes over and starts drawing “heat” (hatred and boos) from the fans. The babyface teases a comeback, but gets cut off by the heel, whetting the audience’s appetite for a big babyface flurry. The babyface finally turns things around, getting the crowd hyped to a fever pitch. And then comes the ending—a well-earned and noble victory for the good guy, or a dirty win stolen by a dastardly, cheating heel. All matches follow this formula with obvious variations to make each bout unique, and if that isn’t verse/chorus/verse/chorus/bridge/chorus in the context of sweaty men or women in tights flying around a squared circle, I don’t know what else to call it. If you’re good at music theory, maybe at some point you do get a chance to earn some real money at this weird gig. If you’re good at building a match, maybe at some point you get to earn some money in an even weirder gig.

Hitting “play” on that tape and hearing Stone’s words—”We had the best jobbers in the country”—fills me with a weird sense of local pride now that I know the story of the MWA, this hiccup in pro wrestling history. Hundreds of small-time promotions come and go, as do thousands of local bands, full of local “jobber” guitarists, drummers, accordionists, etc. But in 1986, Milwaukee was part of the bedrock of something that was expanding into a billion-dollar industry. While Andre the Giant and Hulk Hogan were about to sell out the Pontiac Silverdome, Pete Sanchez, Mike Richards, and Tom “Rocky” Stone were holding down the fort on Saturday mornings with the WWF, and on ESPN with the AWA. They bumped around the ring for the top guys so they could draw top houses. Knowing they were getting their reps in during a weekend loop of bars around the Milwaukee area makes me smile. Of course blue-collar Milwaukee would be ground zero for some of the better jobbers of the day. Locals get shit done, even if their “jobs” are sometimes lost to the ages, only bubbling to the surface in the bargain bin of a local record store, or on weird, unlabeled bootleg video tapes with no audio.

Exclusive articles, podcasts, and more. Support Milwaukee Record on Patreon.

RELATED ARTICLES

• 30 years ago, a WCW PPV at the Milwaukee Theater changed pro wrestling