Christopher Porterfield loves America. And he loves the Milwaukee Bucks. So when the organization invited him to perform the national anthem on the season’s opening night, Field Report’s frontman was excited. But he had some reservations. Anthem protests are sweeping through the sports world, with athletes controversially taking a knee for “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Porterfield wanted to be sensitive to those feelings while performing.

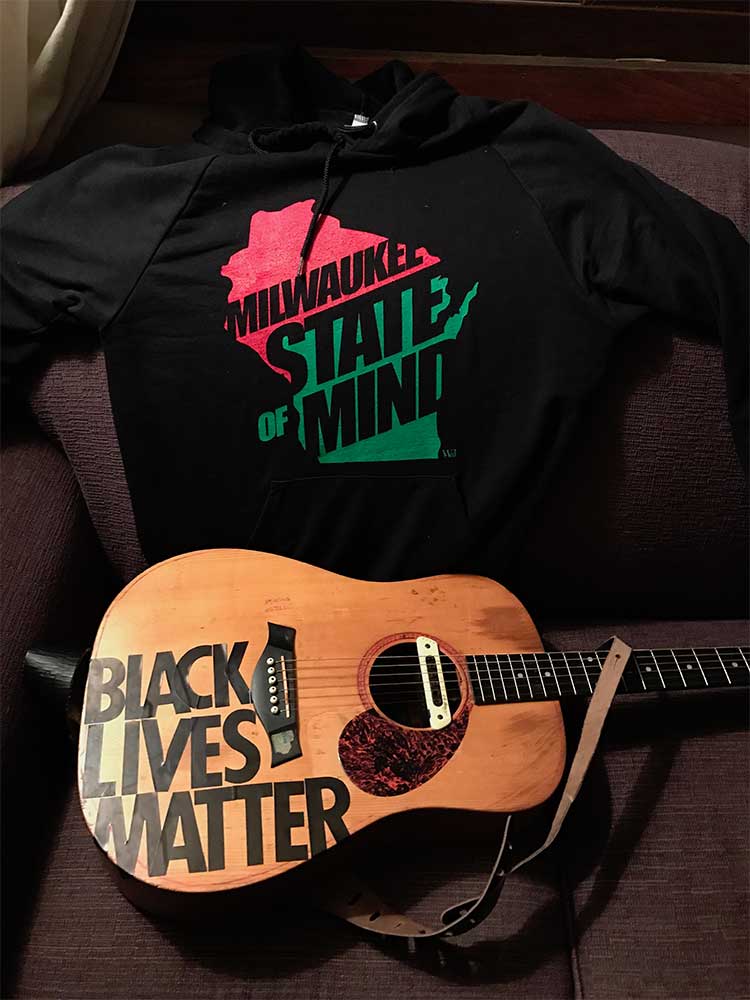

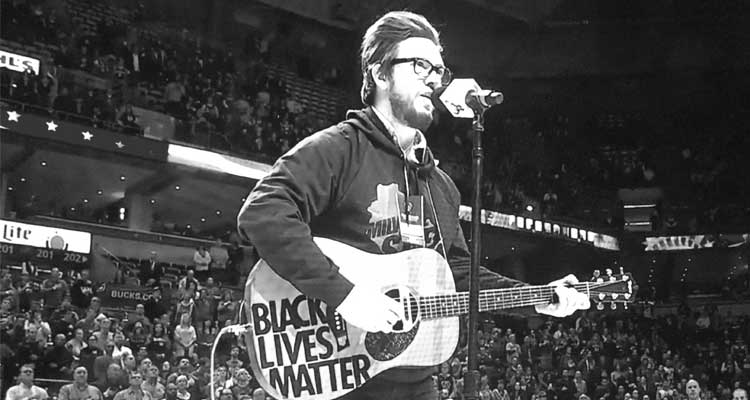

The solution was to adhere stickers to his guitar that spelled out “BLACK LIVES MATTER.” And he played and sang while sporting a sweatshirt by Terrell Harris of Words & Images that read, “Milwaukee State of Mind” in traditional African colors.

Just last night, the Philadelphia 76ers prevented a young black woman from performing the anthem because she was wearing a “We Matter” T-shirt. So while local AM talk radio hosts clutched their collective pearls over Porterfield’s audacity, Milwaukee Record caught up with the man himself to ask where the idea originated, how the Bucks reacted, and what he’d hoped to accomplish with his actions.

Milwaukee Record: In today’s climate, that took some bravery to make such a statement while performing the anthem. Did you give the Bucks a heads-up ahead of time?

Christopher Porterfield: The Bucks did not know ahead of time, but I did intentionally show up at soundcheck in the afternoon with that guitar and that sweatshirt. No one said anything to me, one way or the other. Even after it was over, no one from the Bucks organization said anything. But they deserve thanks and praise and respect for allowing me to express the message.

MR: Did you have any qualms about performing the anthem at a professional sports event given everything that’s been going on?

CP: I had reservations about doing the anthem at all. Suddenly, it became a political choice that people feel deeply about, which speaks to the power of it all. The Bucks reached out in August. I wanted to continue to work with a team and an organization that has been good to me and I am a fan of. I like singing the anthem—I’ve done it before for charity softball games and the like. I struggled with it. Ultimately, as a barely-but-a-little-bit known figure in a city with a deep racial wound running through it, I wanted to be a conducting material for the energy, not a stop. But I didn’t want to make it about me. It’s only about amplifying the message on a different frequency.

MR: How did you approach what you could do to make a statement?

MR: How did you approach what you could do to make a statement?

CP: I reached out to a few friends for advice: Simon Balto, an old friend and a history professor at Ball State, and Rep. Mandela Barnes. Rep. Barnes connected me with Terrell Harris, owner of Words & Images. I spoke with Terrell about a custom shirt, but we decided on the “Milwaukee State of Mind” in African colors. I put the stickers on the guitar for the anthem. They won’t be coming off. It’s a tiny piece of my white skin to put in the game.

MR: Did any of the Bucks players react?

CP: I was standing at the scorer’s table before the anthem with the guitar strapped on and Jabari Parker [who has been demonstrative in his support of Colin Kaepernick – ed.] came over to me and gave me a hug and said thanks. That was a generous and reassuring gesture. I know that in the NBA there are very specific guidelines for player conduct during the anthem. Part of what I did was for them, knowing that they weren’t allowed to express the message.

MR: Did you think about taking a knee?

CP: I was uniquely positioned to amplify a signal. I wrestled with it. I didn’t take a knee. But I had a moral responsibility to conduct the energy. The best way that I can see for our society to improve is if people who look like me try, every day, like brushing our teeth, to be conductors and not insulators. To listen to other voices.

I didn’t take a knee because I respect the people who have served our country deeply. I love America, but I love it because we are aiming at a more perfect union. We can do better. We have to.