“Being existentially lost has a smell; the room is drowning in it. Like grease and beer and sourness. I breathe out of my mouth, get closer. Hakol le’tova, I remind myself. Everything happens for a reason.”

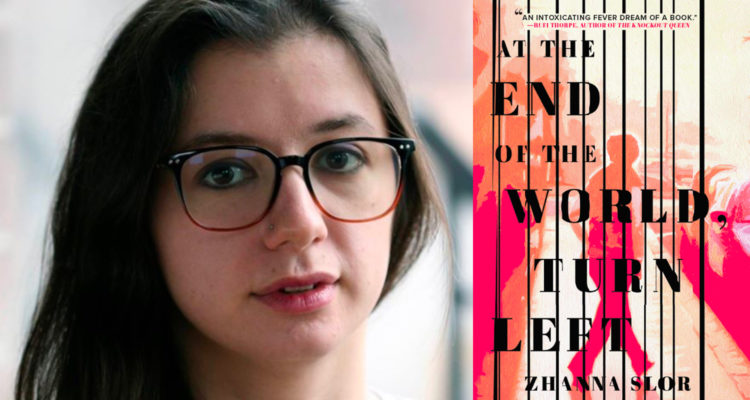

So goes a typically sensorial passage in Zhanna Slor‘s debut novel, At The End Of The World, Turn Left. (Pre-order it HERE.) The book tells the story of Masha, a young Jewish-Russian woman who returns to her old American stomping grounds in search of her younger sister Anna. Sinister friends, family secrets, cryptic messages, and questions of identity all figure into a shaggy-dog coming-of-age mystery that progresses like a half-remembered dream. “Lying is supposed to be a thing of the past, like all the drugs and sleeping around I’d done during that brief time of flailing around in the abyss of adulthood,” Masha tells herself at one point. “One day in Milwaukee is already turning me into a bad Jew. A bad person.”

But it’s the particulars of At The End Of The World, Turn Left that set it apart: Masha’s old American neighborhood is Milwaukee’s own Riverwest, and the action takes place in late 2007 and early 2008. Slor, who lived in Riverwest at the time (she now calls Bay View home), perfectly captures the neighborhood’s sights, sounds, and smells, all the while struggling with what it all means. Any Milwaukee reader familiar with the time and place will surely come across something (or someone) that rings a bell.

Before a Lion’s Tooth-organized launch party April 20 at the Sugar Maple, Milwaukee Record spoke to Slor via email about Riverwest, her characters’ Jewish-Russian backgrounds, and a work in progress described as “Buffy meets Gilmore Girls with a Russian, magical twist.”

Milwaukee Record: More than simply being set in Riverwest, your book seems to be a reckoning with Riverwest. Masha returns to find she’s perhaps outgrown the neighborhood and what it represents. Can you talk about your history with Riverwest and how it informed your book? Why the decision to set it in 2008?

Zhanna Slor: There were a few reasons to set it in 2007-2008—one is that I remember that time period really well. It was my last year in the college bubble and a very transformative and emotional time for me. Two is that it’s before smartphones became popular. I didn’t want to write about a bunch of people sitting at a bar just checking their Facebook and posting Insta stories the entire time, which is a more accurate description of modern times. Before iPhones, you would constantly be talking to strangers (or friends) when you were out and about in Riverwest and it wasn’t weird at all. I know not everyone is attached to their phones now either, but it changed the dynamic of social interactions a lot, and therefore it would have changed the setting a lot as well. In 2008, lots of my friends didn’t even have a phone—I’d have to just go walking around Riverwest to find them or run into them at Fuel.

You’re also right that Masha had a sort of reckoning with Riverwest. Masha is not based on me at all, but when I was in my mid-twenties and living in Chicago, I definitely shared some of her mixed feelings towards Riverwest. I had to come back to Milwaukee pretty frequently because my mother was ill at the time, and I remember being very frustrated with my former friends and the Riverwest community in general—this frustration only went away because I stayed in Chicago for so long. Riverwest eventually became just some place I lived once. When you’re young, the friendships you make can feel like these train wrecks that you will never be able to unravel yourself from—which can be both good and bad—but then as you get older, people change a lot. It’s not necessarily the case that your college best friend remains your best friend into your thirties. It took a long time for me to understand that it’s just a natural part of growing up. I think I wanted to blame Riverwest, or the people I knew in Riverwest, but it was much more complicated than that, which is sort of what I wanted to portray through Masha’s POV in the book.

MR: The book is also a multi-generational exploration of the characters’ Jewish-Russian identities. Masha and Anna, as well as their parents and grandparents, all relate to their backgrounds differently. How did your own background inform this aspect of the book?

ZS: The questions surrounding their Russian-Jewish identity are ones that I’ve had for basically my entire life, so it was very important to keep some of those aspects autobiographical. I really struggled with being Russian and Jewish growing up, especially when I was in my pre-teen and teen years, because by that point we had left Milwaukee and lived far away from the rest of our family and the rest of the Russian/Jewish community. That said, I didn’t really feel like I belonged in that community anyway, being a very artistic and angsty young person. Nor did I fit with my peers in the middle of nowhere Wisconsin, who were all much better off financially and had vastly different interests. I felt like I didn’t really belong to any culture, until I moved to Riverwest. As much as Masha makes fun of Riverwest, it was also a place she loved; in some ways, like she says in the first couple chapters, seeing Riverwest is like seeing an ex-boyfriend.

I think the places we live are so important to our sense of belonging and identity. As someone who has moved around so much, I’m still not entirely sure what “home” means, and that’s another theme I wanted to explore in the book. In some ways, Masha and Anna have too many homes; in other ways, they don’t have enough. They also act a little bit differently depending on where they are and what community they’re in. Masha was really into punk, but you don’t see that when she’s talking about her life in Israel, for example. Anna is an artist, but she barely talks about art with her family. They are very separate identities. As for her parents, they didn’t really have these problems with identity, because they were so much older when they arrived in the U.S., and entirely focused on finding work and raising their children. And the grandparents, who were holocaust survivors, were just happy to be alive and out of the USSR. Identity is more an issue for younger people to tackle, at least those who have the time to think about it.

MR: Finally, the book is also a mystery novel, with some unexpected (and exciting) dashes of crime. Was it always your intent to write your debut novel in these genres?

ZS: No, not at all. It started as an essay collection, actually, and I had sold it to a different publisher as an essay collection. The editor and I spent a whole year turning it into a memoir before realizing it just didn’t have a good plot arc for that—my life was just not that exciting! So then I threw it out and started over, using my 19-year-old self as a launching point for the character of Anna (she is much more likable than I was, though), but making up a whole new plot for her. Only when I met my current editor did I turn it into a crime book. Until then it was pretty literary, and the plot was far less tense. But my publisher only does crime/thrillers, and my editor kept telling me: this is great, but we are a crime publisher, we need more crime! Those parts were the hardest for me to write because I got so stressed out for my characters. But I love how it turned out, and I am so glad my editor pushed it in that direction.

MR: The book begins with Masha searching for her sister. One of the earliest surprises is when it jumps to Anna’s point of view a few months earlier. Was it always your plan to tell the story from both perspectives? How did you settle on the overall structure of the book?

ZS: No, for a long time the entire book was just Anna, and it just didn’t work at all. Masha came into it a bit later, when Tim Hennessey asked me to write a story for the Milwaukee Noir book that was published a few years back. As I was writing it, I knew it had to be in Riverwest, and I wanted it to be the same time period as well. Only once I finished the story (which didn’t end up making it into the Milwaukee Noir book because it conflicted with my former publisher’s original pub date), did I realize it would really save this novel. I’m actually glad we didn’t publish the short story though, because it changed a LOT since then.

MR: There are plenty of Riverwest and Milwaukee locations that make appearances—Fuel, Bremen Cafe, Foundation, UWM, Landmark Lanes, etc.—and plenty of characters that seem to be based on real people. How did you decide what to include and what not to include?

ZS: Yes, lots of characters are based on real people, and I also wanted to use the real names of all the local bars and coffee shops, because Riverwest became almost a character in itself, and I wanted to portray it as authentically as possible. The places I chose for scenes just happened to be the ones I frequented the most often—to me, they really “make” Riverwest what it is. I also wanted to create this small snapshot of life in this tiny neighborhood in this particular time period. I have always wanted to write about Riverwest, and always the pre-2010 version of Riverwest, because that’s what I am familiar with—I moved to Chicago in 2010, and met my husband in 2011, and now, even though we recently moved back to Milwaukee, we have a 2-year-old, and I can’t remember the last time I went to a party or got too drunk at a bar. Even if I were to return to Riverwest, it would be a very different version of Riverwest. Instead of chain-smoking at punk shows, I’d probably be chasing my daughter around the park, or listening to an audiobook, which is how I get more of my reading done these days. I’ve actually been avoiding Riverwest since I heard Fuel closed—that makes me sad.

MR: What’s next?

ZS: I’m currently finishing up a draft of this supernatural YA book that I started writing around the same time as At The End Of

The World, Turn Left. It’s about a set of orphaned Ukrainian twins living in Buffalo with their uncle. Lena, the main character, works for him at his monument company, where she engraves portraits into tombstones; then the portraits start talking to her, leading her into this fun (but dark) teenage adventure to find out what really happened to her family in Ukraine. It’s kind of like Buffy meets Gilmore Girls with a Russian, magical twist.

I can’t work on just one book at a time, because I get really sick of it after a while, so I also recently started another YA book—it’s a modern retelling of Sleeping Beauty, but it’s set in 2046. That’s been really fun so far.

Listen to a Spotify playlist inspired by At The End Of The World, Turn Left, and Riverwest circa 2007-08.