Summer in Milwaukee is the best; summer in the Midwest is even better. Join Milwaukee Record and Miller High Life as we search the city and beyond for the Spirit Of Summer.

To explore the Horicon Marsh is to explore an awesome natural resource rich with history, beauty, and contradiction. It’s the largest freshwater cattail marsh in the United States, a 33,000-acre glacial formation located on the border of Dodge and Fond du Lac counties. It’s a natural wonder marked by man’s folly and its late-in-the-game benevolence. It’s a wildlife refuge split in two, managed by both the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the northern two-thirds) and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (the southern third). It’s a paradise for hunters, hikers, anglers, and kayakers, yet the bulk of it remains remote and mysterious. To explore the Horicon Marsh—to really explore it—is to explore a place both tightly controlled and wonderfully wild. It really is something.

It’s easy to get sentimental about the Marsh. I grew up in Mayville, population 5,000-ish, and the Marsh was almost literally in my backyard. (Horicon is the namesake, but Mayville is still known as the “Gateway to the Marsh.”) Thinking about it now brings back a rush of memories: fishing at my grandfather’s hunting cabin with buckets full of bullheads, building ridiculously elaborate forts with my friends, sitting on my father’s lap and steering the car as he took our family for a drive. Growing up, the Marsh was a simple fact of life, a place where generations of my family lived and played. It’s still there today, as vast and immovable as ever.

And yet it’s easy to take the Marsh for granted. I did just that throughout my teens and 20s, electing to ignore my hometown wonder and instead focus on geeky pursuits (teens) and drunken idiocy (20s). But in recent years I’ve dipped my toes back into its peat-filled waters. I’ve started to fish there, hunt there, spend time with my family there. I’ve started to make up for lost time.

The Horicon Marsh is only 60-some miles from Milwaukee, making it easily accessible for even the most hardened city dweller. If you’ve never visited and you’re so inclined, you can make up for lost time, too. Here a quick look at its two sides:

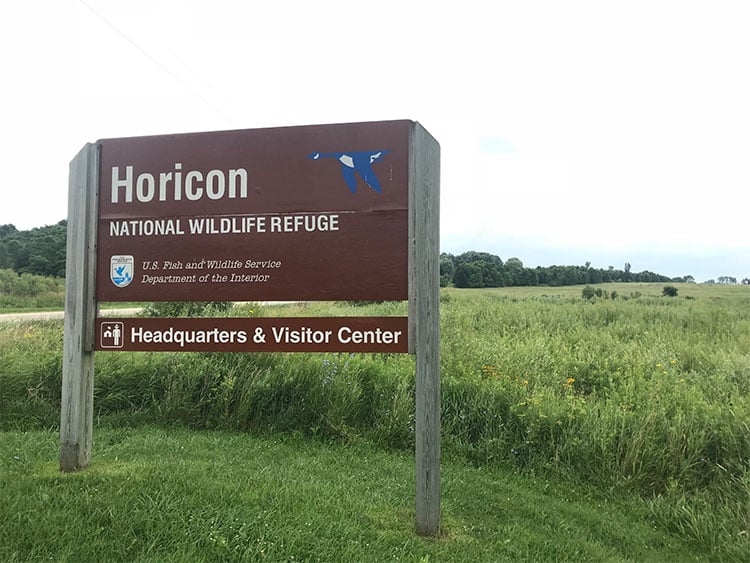

The northern portion of the Horicon Marsh—the Horicon National Wildlife Refuge—checks in at a sprawling 22,000 acres. It was established on July 16, 1941. If you’re looking for wide open vistas and picturesque hiking trails, as well as bird watching opportunities and oodles of waterfowl, the federal chunk of the Marsh is your jam.

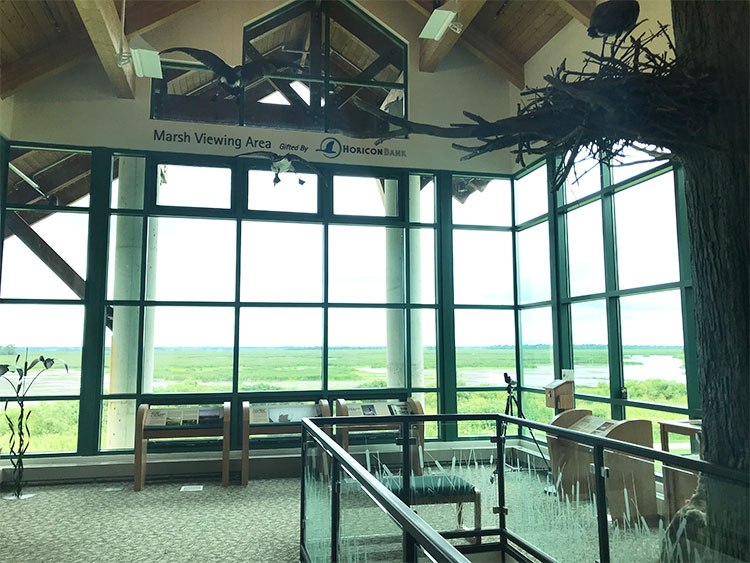

You’ll find a small visitor’s center on the east edge of the refuge. A lovely nature center—complete with a terrific auto tour route, a hiking route, and a bike path—is located on the northwest corner. An observation deck at the visitor’s center gives a thumbnail sketch of just what the Marsh is:

Horicon Marsh is a shallow, peat-filled lake bed scoured out of limestone by the Green Bay lobe of the massive Wisconsin glacier. The glacier entered this area about 70,000 years ago and receded about 12,000 years ago. The same layer of rock that forms the gentle hills to the east of the marsh extends 500 miles to the east and is the same rock layer over which the Niagara River plunges at Niagara Falls. This Niagara Escarpment bordering the marsh, commonly referred to as “The Ledge” extends for 230 miles in the state of Wisconsin alone. The marsh itself is approximately 14 miles long and ranges from 3-5 miles in width.

Curiously, the bird most commonly associated with the Marsh—the Canada goose—wasn’t the area’s original star. The Marsh wasn’t managed for Canada geese until the late 1940s and early 1950s. Restoration and intensive agriculture in the surrounding area helped the bird thrive. Now, every fall (usually around mid-September), tens of thousands of geese stop over in the Marsh as they migrate south. The DNR explains:

The geese that stop here in migration are part of the Mississippi Valley Population (MVP) of Canada geese. This is a mid-sized goose ranging from 7 to 10 pounds. In North America, there are several million Canada geese, consisting of 12 distinct subspecies. There are more than 1 million Canada geese in the MVP, with about 100,000 to 200,000 stopping at Horicon Marsh each fall. Another race, or subspecies, nests on the marsh and throughout Wisconsin, called the giant Canada goose.

Elsewhere, a terrific off-the-beaten-path viewing spot is Blackbird Hill, so named because that’s what my dad always called it and because that’s where he used to take me to shoot blackbirds with a shotgun. There’s a small parking lot and an observation deck on top of the hill, and the view is beautiful. It’s perfect for photographing unwitting children as a storm rolls in overhead.

The Main Dike Road is another highlight of the federal portion of the Marsh. Cars can drive the gravel road for seemingly ever, spotting herons, ducks, and dozens of other critters along the way. This is where my family would often “go for a drive.” This is where my father would let me and my younger brothers sit on his lap and take the wheel. This is where the Marsh is at its most generous, its most abundant, its most wild.

Though roughly half the size of its northern counterpart, the Horicon Marsh State Wildlife Area is where the action’s at. This is the place to go for canoeing, kayaking, and fishing (all along the Rock River), as well as hiking, cross country skiing, and hunting. There are public boat landings near Green Head Road and in Horicon itself. A pair grandfathered-in hunting clubs make their homes here; down river, remnants of even older structures remain.

The Horicon Marsh Education and Visitor Center is located on the southeast corner of the wildlife area, just a stone’s throw from Horicon itself. It’s a large and modern facility and it’s absolutely worth the visit.

In the basement of the Education and Visitor Center is the Horicon Marsh Explorium, an absurdly state-of-the-art interactive museum dedicated to the history and preservation of the Marsh. Built in 2015 for a cool $3.7 million, the Explorium tells the story of the Marsh’s prehistoric beginnings, its Native American years, and its role in state and federal wildlife conservation today. And in a wonderfully WTF wrinkle, the Explorium does all this by following the journey of a rock—a rock voiced by a rather convincing Morgan Freeman sound-alike. The $6 admission fee seems a bit low for this unique pleasure.

There’s a book called Wild Goose Marsh: Horicon Stopover, published in 1972, written by Robert E. Gard and featuring photographs by Edgar G. Mueller. My aunt gave it to me years ago, and it bears an inscription from Gard to my grandparents: “To Dooly and Ida. For helping me out so many times when I was in need.”

Mueller, meanwhile, is something of a Mayville legend. He diligently photographed the city and the Marsh for 65 years, until his death in 2001. On the final page of Wild Goose Marsh, he shows his talent as a writer, too:

If you’ve never been on the Great Marsh in the evening, Ed says, you may be missing life’s finest hour.

And if you have, you may find it difficult to describe that experience.

Inspired by the call of Spring, Dorothy and I trekked out to Townline ditch near the Ernie Bleifuss farms shortly after sundown to see and hear the sights and sounds of budding nature.

Horicon Marsh is probably the best place in America to do this.

An almost complete absence of breeze permitted greening willows to reflect in quiet waters like a huge image in a man-made mirror. Unlike the imperfections in man-made objects, this was nature-perfect, complete with sound effects.

A symphony amplified by Marsh creatures. Millions of crickets, frogs, egrets…thousands of small birds, many varieties chirping lustily, and mallards and teal drifting serenely.

In the distance a V takes shape on the quiet water temporarily distorting the willowy images reflected by the clear sky overhead. Still enough light for eyes now adjusting to night vision, but hardly sufficient for available light photography.

Not more than 30 feet before us emerged the maker of that V. I’ll call this muskrat Tom. Tom entertained us for a quarter hour as he silently worked over one clump of sod after another along the fenced shoreline.

Then, as quietly as he had come, Tom disappeared.

There were no dull moments.

Overhead a quintet of Canada geese announced their arrival with loud honking, while a loon in the far distance uttered his wild cry.

Seconds later the geese set their wings for a perfect landing on the mirrored surface.

Just like in the time of creation, commented Dorothy so softly I hardly heard what she said. I was too busy just feeling.

That about sums it up. You can write as many words as you like about the Marsh, take as many pictures as you like. But the only way to truly experience it is to go there and simply watch. Simply feel. It’s easy to make up for lost time when time stands still.