Jim Abbott’s Major League career lasted a decade. It began in California and ended in Milwaukee. Along the way, he totaled 87 wins, a 4.25 ERA, 888 strikeouts, and a no-hitter. He began his journey as a rookie for the Angels in 1989, tossed that no-no as a member of the Yankees, continued to beat the odds with the White Sox, and for a curtain call, he tallied both his career hits and knocked in all three of his career RBI as a member of the ’99 Milwaukee Brewers—roughly a month before his remarkable career ended.

But before he could bask in those achievements, Abbott had to battle great adversity. Doing so required an even greater work ethic, as well as the drive to overcome doubts, including the most potent of its kind: Self-doubt.

The southpaw was born in Flint, Michigan in 1967. His left arm was longer than his right, which ended in a wrist that resembled a balled-up fist to which no fingers were attached. He became more aware of the limb difference in grade school, when he endured teasing on the playground and awkward glances in class. Undaunted, he was thrilled when his dad bought him his first glove—a cheap plastic one from the drug store, but still, a baseball glove. Father and son set about playing catch, with a bit of problem-solving involved.

“We just tried to figure out how I could twirl the glove towards my body and cradle the ball in the glove, and then take it out and throw, and then be able to slip the glove back on,” Abbott said in an interview.

He practiced by firing a ball against a brick wall and making the transfer of his glove quicker than the return of the Spalding as it ricocheted to the spot where it was thrown. Abbott did this routine countless times. Eventually, he could catch his hardest heat when it caromed with vengeance off the hard surface.

While investing so much time and effort into this routine, he also needed to master the art of pitching: Mechanics, location, command, velocity, psychology, changing arm angles and speeds and bends. Jim Abbott might have outworked every other hurler who made it to The Show.

With practice came confidence, and by high school, he was a rising star at Flint Central—where, no big deal, he was also a standout quarterback. As a senior, he dominated on the mound, throwing four no-hitters and boasting an ERA of 0.76. Next, he was drafted by the Blue Jays, but instead, he opted to play college ball for the Michigan Wolverines. His record was a sterling 26-8 in three seasons, and in 1987, he became the first baseball player to earn the James E. Sullivan Award for the country’s best amateur athlete.

Abbott was on the verge of his Major League debut when he realized it would be sweet to win a gold medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul—so he did that, too. Though baseball was deemed “unofficial” at the time, he went the distance in the decisive game and brought home some cool hardware.

He remains the last ballplayer to skip the minors altogether, debuting as a starter for the California Angels in 1989. As a rookie, he was 12-12, and he kept his ERA a shade under 4.00. Two seasons later, he was brilliant, finishing with a record of 18-11, an ERA of 2.89, and placing third in American League Cy Young voting.

His ERA improved in ’92, but he was hampered by another misfortune: Poor run support. His record of 7-15 must have made him expendable to the Angels. The lefty was traded to the Yankees in the offseason. New York was the site of Abbott’s best day as a pro.

On September 4, 1993, the fans at Yankee Stadium were treated to one of the most awe-inspiring triumphs in sports history. Abbott bested a potent Indians lineup that featured Kenny Lofton, Carlos Baerga, Albert Belle, and Manny Ramirez, and surrendered no hits over nine historic innings. His masterpiece remains and inspiration today.

In 1995, he signed with the Chicago White Sox, who fell out of contention and then sent him back to the Angels. Abbott finished the year with a 3.70 ERA and a mark of 11-8, stats many of his pitching counterparts with two hands would’ve been happy to have.

Unfortunately, in 1996, his ERA exploded to 7.48. It was ugly. His record was an uglier 2-18. Even the dreamers get bruised and beaten. Abbott sat out the ’97 season. But true to his determination, he came back strong in an abbreviated 1998 showing. After retaking the mound with the White Sox and winning all five of his starts, Abbott joined the Brewers in 1999. It was the team’s second year in the National League, which posed a problem. He had to hit.

Throughout his career, teams had always tried bunting on him, but Jim Abbott shut that weak stuff down. Fielding was never an issue, but hitting with one hand was a new challenge.

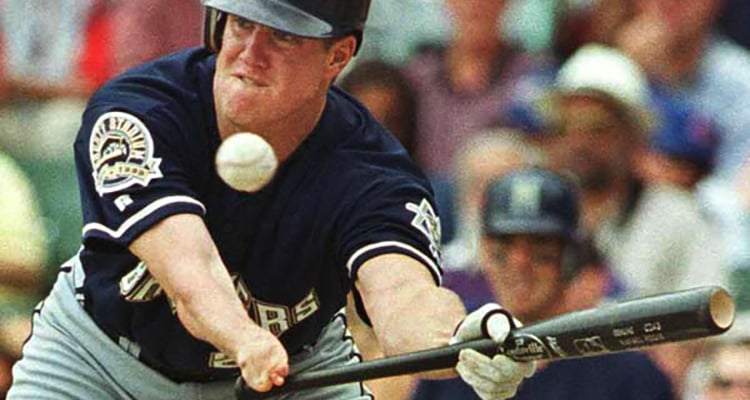

In the twilight of his career, with his pitching stats trending the wrong way on a fifth-place team, Abbott still found ways to amaze. It was June 15 of the year Prince (The Artist Formerly Known As…not Fielder) made famous and the Brewers hosted the Chicago Cubs. With two outs and runners on first and second, Cubs hurler Jon Lieber was eager to get out of a jam with Abbott, the number nine hitter, at the plate. With his left hand squeezing the bat and the end of his right wrist pressed against the handle, Abbott cracked the first pitch and hit a liner into shallow center to drive in a run. It took close to 10 years, but this underdog story now features some offensive accolades as well.

You’d think Lieber would’ve learned to never underestimate the pride of Flint, Michigan—especially when runners were in scoring position. Think again. Abbott connected on a two-RBI single against Lieber on June 30, 1999—exactly 18 years ago today.

The hero of our story retired before the new millennium. In fact, his last Major League appearance came just three weeks after his final hit. He’s a motivational speaker now. One might think he was driven to greatness by the naysayers and bullies, but the opposite was true.

“At every level, I remember having self-doubt. Moments of uncertainty,” Abbott said in an interview. “And every time, there was always somebody there who told me that I could do it.”

There will never be another Jim Abbott. This unlikely sports hero was an Olympic medalist, a member of the no-hitter club, and a (mostly) effective professional athlete for a decade. Metaphorically speaking, he accomplished all these amazing things with one hand tied behind his back. And he saved his last great baseball moment for the Brewers.