On December 1, 1934, Beatrice Blake called for help. Her husband, Arthur, had been ill for several weeks, and his condition was worsening. What started out as a severe cold quickly led to a fever, chills, and significant chest pains. Now Arthur was coughing up bright red gobs of blood.

Arthur hadn’t been well for a long time. He was never the same after his bout with pneumonia a year ago, which had led to him spending three weeks at Milwaukee County General Hospital. Arthur had lost a lot of weight in the last year—he was now gaunt and frail, looking far older than his age of 38 years. But he hadn’t seen a doctor since he was discharged from the hospital. After all, doctors cost money, and Arthur and Beatrice were broke.

Truth be told, Arthur hadn’t been well ever since he lost his job a few years ago. His job was everything to him. It brought him joy. It brought other people joy. And it had given Arthur—a blind man—the chance to be self-sufficient when so many other blind people in America eked out a living by begging in the streets. But the company that employed him had gone out of business, and no one else seemed to have any use for his talents.

It was just after midnight when authorities arrived at the Blake home. Arthur’s condition was dire—his body was in clear distress, and his skin was turning purple due to lack of oxygen. Arthur was brought to Milwaukee County Emergency Hospital, just across from the Eagles Club on Wisconsin Avenue. But it was too late. By the time Arthur reached the hospital, he was dead.

A coroner’s autopsy confirmed that Arthur Blake had died of complications from tuberculosis. With Beatrice unable to afford a proper burial, Milwaukee County provided burial assistance and took some of Arthur’s organs as “donations” to offset the cost. Arthur was buried on December 5, 1934, in an unmarked grave at the far edge of Evergreen Cemetery near Highway 57. No Milwaukee newspaper made any mention of his death, funeral, or burial.

It’s especially heartbreaking to ponder Arthur Blake’s untimely and tragic death given what we know now: Arthur Blake, better known by his stage name Blind Blake, was one of the greatest American musicians of the 20th century. His guitar playing was breathtaking in its intricacies, earning him the posthumous moniker “King of Ragtime Guitar.” But he was also a brilliant songwriter and dynamic showman, and even his later recordings show him continuously working to innovate. On this 87th anniversary of his sad death, the time has come for Milwaukee to acknowledge and embrace Blind Blake as an important part of our city’s history.

Though so much of Arthur Blake’s story remains a mystery, recent research suggests that he was born in Newport News, Virginia, to Winter and Alice Blake. We don’t know if Blake was born blind, but we do know that his disability would have made his life especially hard in early 20th century America. Busking—or playing music on street corners for tips—was often taken up by many a blind musician as an alternative to begging. Whether or not this is how Arthur got his start, his obvious talents proved adept at earning a living playing live music.

Additional research suggests that Arthur lived a traveling musician’s life, with stories of him playing around Atlanta, Detroit, and even Bristol, Tennessee. But Blake’s main hub was Jacksonville, Florida, where he kept an apartment and learned to improvise his repertoire to wherever he was playing. Eventually, a talent scout recommended Blake to Wisconsin’s Paramount Records, where he would become one of the company’s biggest recording stars.

Paramount Records was a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company in Port Washington. These records, cheaply made and recorded on a tight budget, existed solely to encourage sales of the Chair Company’s phonograph cabinets (somewhat like how iTunes was created to encourage sales of iPods). Paramount was able to find a niche in marketing to Black record buyers, and Blind Blake’s 1926 instrumental “West Coast Blues” became a massive hit that catapulted him to the top tier of Paramount artists. In this tune, we hear Blake calling out dance steps and cracking jokes to a joyful ragtime beat. “I got something that’ll make ya feel good!” Blake laughs as he barrels into a killer guitar lick. “I know it’s good. I made it good.”

Blake took up a residence in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, where he would have had easy access to both Paramount’s downtown recording studio and Bronzeville’s array of concert halls and dance clubs. Paramount utilized Blake as a go-to session musician for several Paramount performers, but he remained an incredibly prolific solo artist. In addition to his guitar playing, Blake was also a charismatic singer and skilled lyricist, and several of his songs were no doubt popular with Bronzeville’s late night music scene. Blake seemed especially at home with the sexually suggestive hokum music, as proven by songs like “Diddie Wah Diddie” and “Too Tight Blues.”

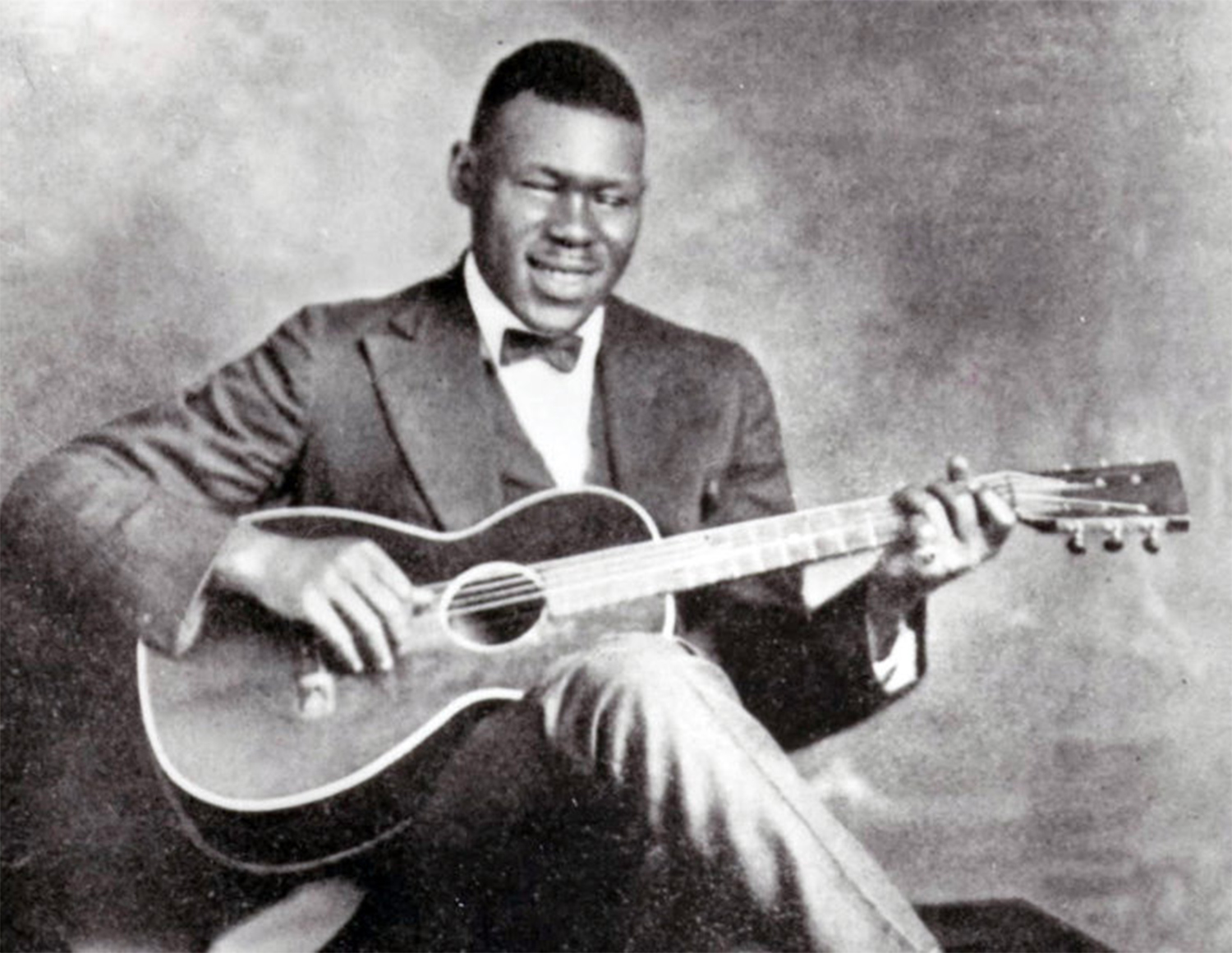

Blake soon became a fixture of Paramount’s promotion machine, with his name and likeness being used in several ads in the Chicago Defender newspaper. In 1927, Paramount featured Blake in their souvenir songbook The Paramount Book Of Blues. The songbook even included a short biography, in which Paramount’s marketers wrote: “[Blake] could not see the things that others saw—but he had a better gift. A gift of an inner vision, that allowed him to see things more beautiful.” Their descriptions of Blake’s demeanor seem to be apt—Blake was remembered by his friends as good-humored and jovial, and fellow musician Big Bill Broonzy called him “the jolliest fellow you ever seen in your life.”

While there is an undeniable sense of joy in much of Blake’s music, he seems just as comfortable performing darker subject matter. In “Rope Stretching Blues,” Blake’s narrator kills an intruder and awaits an inevitable death sentence. In “Third Degree Blues,” Blake is detained and forced to confess to an unknown crime in rather Kafkaesque fashion. And there’s an unsettling grimness within such songs as “Early Morning Blues,” in which Blake sneers, “The day you dare to quit me, baby, that’s the day you die.” Yet Blake’s charm remains front and center throughout, giving these songs an eerie and ironic quality.

Blake’s pièce de résistance may very well be his euphoric boogie woogie instrumental “Hastings Street,” recorded in 1929 with Detroit piano legend Charlie Spand. Blake’s guitar effortlessly compliments Spand’s rolling piano, with Blake gleefully name-dropping streets from Detroit’s red light district.

Altogether, Blake would make about 80 recordings for Paramount, but the recording industry was in serious trouble following the stock market crash of 1929. Records were increasingly seen as a luxury, especially when radio provided hours of music for free. To save on costs, Paramount moved its main recording studio from Chicago to their record pressing plant in Grafton, Wisconsin, where artists would record just a short distance from Paramount’s Port Washington headquarters.

Blake moved to the north side of Milwaukee, presumably to be closer to the new Grafton recording studio. He married Beatrice McGee in 1931, and the Blakes lived at 621 W. Brown St. (today the site of Beckum Park). But Paramount’s sales continued to plummet, and in this era we hear Blake experimenting with new sounds and styles, seemingly throwing whatever he could to the wall to see what might stick. Sometimes this meant recording formulaic retreads of his earlier output or derivatives of other pop songs, but there were still glimpses of his brilliance. On his record “Miss Emma Liza,” (considered lost until a copy was found at a flea market in 2012), Blake channels Dixieland jazz and sings in a hilarious falsetto. On the record’s flip side, “Dissatisfied Blues,” he thunders out a “rapping” beat on his guitar. And in a recorded duet with Papa Charlie Jackson, we hear more of Blake’s trademark wit: “My name is Arthur Blake,” he smirks, “and I’m the Arthur of many things.”

But no recording at Paramount—no matter how transcendent—could stop what the Great Depression had wrought. Paramount closed its doors for good in 1932. The top brass in Port Washington went back to focusing on making furniture. And Arthur Blake’s career as a recording musician was over.

When Paramount closed, it seemed that was the last anyone ever heard of Blind Blake. As the years passed and his recordings were rediscovered, rumors abounded about what ever became of this unique visionary. Reverend Gary Davis had said he heard Blake was killed after being run over by a streetcar. Others swore they saw him playing in the streets of Jacksonville years later. It wasn’t until 2011 when researchers discovered what we should have known all along: Arthur Blake had spent his final years in Milwaukee. And it is in Milwaukee where he spends eternity.

In 2012, Blake’s unmarked grave finally received a memorial headstone. The marker shows Blake’s smiling promotional portrait—the same image that graced so many Paramount ads nearly a century ago. Fans and admirers from around the world now make their pilgrimage to Milwaukee’s Glen Oaks (formerly Evergreen) Cemetery to pay their respects. And one need only look up Blind Blake on YouTube to see many a skilled guitarist trying to crack Blake’s secret code, striving to recreate what Blake made seem easy. Yet, when Milwaukee locals consider our city’s musical history, Arthur Blake is almost always overlooked.

This needs to change.

How shall we properly honor a man so respected in his heyday, but whose memory and story have been so neglected within the city where he spent his final years? Clearly, it is not up to me to decide how best to honor Arthur Blake, nor should it be. But I am heartened to think about what mysteries could still be solved by local researchers, historians, and others who might shine a light on a corner of Blake’s life where others didn’t think to look. Hopefully additional research on Arthur Blake will bring a renewed focus on the communities where he resided, which, like Blake himself, are often left out of Milwaukee’s narrative. (At the time of this writing, the grave of Beatrice Blake remains unmarked.)

I personally choose to honor Arthur Blake by celebrating the music he left behind. But there’s still an important fact to consider: In Blake’s time, records were often seen as a novelty and as flawed reproductions of what was always meant to be heard live. And that’s especially true of Blake’s recorded output—however brilliant his records, they are mere hints of who he really was. Arthur Blake’s music was never meant to be listened to alone on a phonograph, let alone a laptop or smartphone. Blake’s music was meant to be heard in a public setting, for it is in such settings where music ceases being private and becomes a social experience. And this is where the exuberant magic of Blind Blake truly manifests, nearly a century after he made his legendary recordings for an unassuming Wisconsin furniture company.

I choose to honor Arthur Blake by cranking his music loud, singing along, and hopefully getting my friends to join in with me so we all feel a bit less scared and alone. This is Arthur Blake’s legacy, his gift to anyone who cares to listen. And when he calls out “Swing your partner and promenade!” we’d be absolute fools to not take his hand and meet him across a space of Milwaukee’s history that spans more than 90 years and counting.

Exclusive articles, podcasts, and more. Support Milwaukee Record on Patreon.