Paul Dorobialski saw the light. The blaring white light from a city utility pole, to be precise, the one that had been burned out or smashed or painted over since the early 1990s. The existence of this light meant Dorobialski could not go on with his theater in the true spirit of “showmanship.” No matter that Dorobialski’s theater was a half-paved outdoor alley with a few rows of folding chairs and a film rear-projected onto a slat of discarded screen hung from a loading dock. A fresh city light bulb: such a flimsy thing to end this theater’s run, Dorobialski thought, mulling the discovery during caretaker rounds at the warehouse next door.

“I came out to do my janitorials, then out to the loading dock, and I looked up and said, ‘Where the hell did all that light come from? Oh no!’ And there it was, bright as could be,” Dorobialski says. “Oh shit.”

Dorobialski had no reasonable way to provide shade that countered this unexpected reemergence of the light for a proper showing of the movie on that week’s handbill, The Maltese Falcon—or anything else. Paul’s Alley Cinema (170 S. 2nd St.), Dorobialski’s shifting and nerdy and self-driven project of a technician’s passion for nearly two decades in Walker’s Point (and much longer if you count Burnham St. backyards and basement water heaters) was closed. Probably.

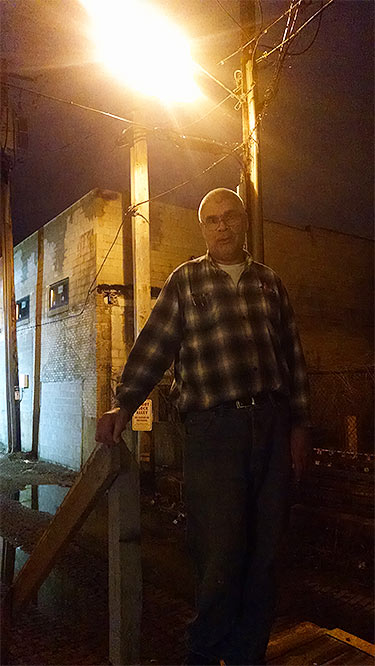

Photo: Paul Dorobialski

Somehow, Dorobialski seems like he should be taking care of a warehouse. On a midweek day in early April, he’s wearing a flannel long-sleeve and worn jeans and a curious number of pens and gauges in his pockets. He has multiple keys and does rounds like a doctor. If—when?—there’s an apocalyptic battle between humans and buildings, Dorobialski will be the quirky scientist who somehow makes it to the White House with a plan destroy all buildings.

In real life, he has a trick knee, soft bulbous knuckles, and, in Technicolor style, a face like Harrison Ford, if that actor had a twin brother who only ate mashed potatoes and didn’t wear an earring to sneak around his age. More pertinently, Dorobialski’s voice and cadence are studies of Sout’ Muhwaukey. By day he works as a mechanic at the Milwaukee Public Museum. He’s a ham radio enthusiast, which in parallel ways explains precisely and absolutely nothing about the guy. When not looking after storage facilities, he’s collecting, tweaking, and selling anything from jukebox equipment to—there’s no other way to say it—lights. Different lights from those found in insulting city alley posts, though he’s meticulous on their variations.

This technical prowess overlaps with a minor encyclopedic brilliance. As Boston’s “More Than a Feeling” rings through cavernous storage floors via speakers he rigged, Dorobialski will outline to you the history of an industrial furnace operator’s former quarters, closing with the related phrase “I’ve seen every type of church pew,” and then give a two-line anecdote that ends with a fart noise emphasis.

On the tour of the warehouse, you meander through his stories to the spots connected to the theater. The basement, for one, includes his personal storage den, a hearty portion of which holds the unused projector, speaker, screen, and movies that comprise Paul’s Alley Cinema. They look useless here rather than out on the loading dock, a.k.a. the theater itself, where viewers watch from waiting room chairs and passersby wonder why parking their Audi so far from the wine bar brought them in view of Back To The Future.

Then, on the tour, you come to the light itself, innocent enough, a funnel of creamy visibility in a nowhere alley. This light cancels whatever is projected on a nearby screen, and will thus keep away the cinema’s audience, whoever that audience could be. The audience is perpetually Dorobialski. His drive is that of an obsessed tradesman, the welder who signs his kid’s names into skyscraper I-beams.

As far as who shows up for the movies since 2001, it tends to be, plainly, the people who show up for the movies. Dorobialski’s cinephile and technician daydreams are fulfilled by purely showing the movies, though he relishes the attention of the random or interested. How many people that may be, he’s not sure. Has it been tens of people? Hundreds? Thousands after that one Jim Stingl article during Summerfest?

You could be excused for missing it. Counter to your non-stop entertainment options as an American, the cinema can be tricky to find, off the 100 block of 2nd St. The line-up is erratic: The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, West Side Story, Three Stooges shorts. Promotion mainly involves a single, neon green photocopied flier taped onto the side of a 2nd St. building, though a friend recently set up a Facebook page. It’s outside the bounds of the city’s typical theater and film festival circuit, though a movie times website listing for Paul’s Alley Cinema alongside those of Marcus Corp. is jokingly printed out and tacked to a corkboard in the warehouse. The movies are free, but there remains more formality and production than your inflatable screen movie nights and event showings. For seven months a clip over the last 15 years, regardless of audience but unless it rained, the movies at Paul’s Alley Cinema would be there. Unless there’s a tactically placed light, and then they don’t.

There could be a dumb solution—throw a rock at the light—but that defies Dorobialski’s appreciation of the neighborhood and search for an inventor’s solution. With no answer discussed directly with the city, Dorobialski has already crafted an ineffectual shade and a type of swinging plate locked into bricks. (These creations are not to be confused with the anti-sway brace—a stick—used to steady the cinema during drafts.)

There could be a dumb solution—throw a rock at the light—but that defies Dorobialski’s appreciation of the neighborhood and search for an inventor’s solution. With no answer discussed directly with the city, Dorobialski has already crafted an ineffectual shade and a type of swinging plate locked into bricks. (These creations are not to be confused with the anti-sway brace—a stick—used to steady the cinema during drafts.)

An aw-shucks defeatism sets in. All the while blaming the light itself, Dorobialski floats a conspiracy that his cinema doesn’t have a place in this next phase of the neighborhood. He’s worked and/or lived here since Bostrom hawked furniture, during Dahmer’s reign of fear, and amid Milwaukee’s “first rave party” (he marveled at the amount of waste in the Oregon St. rave’s port-o-potties). He backtracks himself, with the light as the glaring point of blame rather than tapas restaurants or high-end homes.

“I get along with a lot of people. I don’t run late shows, dusk-to-dawn shows. I’m off the screen before midnight,” he says. Later, on that same train of thought that has changed tracks once or twice, he punctuates it all, inwardly: “Kublai Kahn’s pleasure palace in the new Xanadu has been interrupted!”

Dorobialski’s mechanical acumen and knack for historical detail are the longhand of never forgetting. Although he lives in West Allis now, Dorobialski was raised on 19th and Burnham streets. For his 12th birthday, his parents gave him a hand-cranked 8-millimeter projector. He soon found a way to automate the crank with D batteries. More importantly, he was “movie bound.”

“I used to go over to my neighbor’s house down the block and give movies on the hot water heater because that was the only white surface down in the basement. You watch on that [water heater] as the cowboy trots uphill, downhill, uphill. Reverse CinemaScope.”

During much of the ’70s, he filed, stored, and clerked at Roa’s Films, the feature and educational reel center that once occupied the current Glorioso’s (and Brady Street Pharmacy, with a theater of sorts, in between). For nearly seven years, he was the main projectionist at the Paradise, but he filled in plenty before, during, and after at Ruby Isle, the Uptown, the Oriental, and the Strand, where the projectionist’s booth had a shower in it. (“I imagine the audience could hear you” washing during movies, he concedes.) In early years, he was also an usher at the Modjeska. In the ’80s he fixed the speakers at the Avalon.

During much of the ’70s, he filed, stored, and clerked at Roa’s Films, the feature and educational reel center that once occupied the current Glorioso’s (and Brady Street Pharmacy, with a theater of sorts, in between). For nearly seven years, he was the main projectionist at the Paradise, but he filled in plenty before, during, and after at Ruby Isle, the Uptown, the Oriental, and the Strand, where the projectionist’s booth had a shower in it. (“I imagine the audience could hear you” washing during movies, he concedes.) In early years, he was also an usher at the Modjeska. In the ’80s he fixed the speakers at the Avalon.

Dorobialski also found his first outdoor theater, though not in Walker’s Point. A closeness to film and projection equipment, and a nice new partly white paint job on his parents’ house allowed Dorobialski to air films for the neighborhood. His mother would cook a pot of chicken soup. Coincidentally, he once aired Julie Andrews’s Thoroughly Modern Millie 30 minutes ahead of that night’s CBS broadcast, denting Nielsen statistics in a one-block square. In the theaters or outside, Dorobialski developed a professional approach to timing and presentation, based on the bygone film masters.

“Years ago, that was called showmanship,” he says. “The [theater] manager had to program what short was going to play, if a cartoon was going to play, if there was an orchestra, any vaudeville acts. The stagehands put everything into position and then the organ played a solo before the feature picture. Then, you opened up with your feature film.”

Dorobialski worked the city’s expanse of theaters and earned his Projectionist Union Local No. 164 card. However, when he moved out on his own, his parents gave up on the theater. Come 1998, Dorobialski began work at a different Walker’s Point warehouse. One tedious night, he positioned a military-grade movie projector out an office window and onto a truck trailer moored into a lot off 2nd St. Half-hammered art gallery wanderers paused to watch. Later, Dorobialski discreetly painted a screen onto a Woodrow Wilson-era bridge and wedged speakers where pigeons usually perched. This was the first version of Paul’s unanticipated cinema in Walker’s Point. It lasted three years with a small lull before he assumed oversight of another warehouse and took with him a refined cinema in a changing neighborhood.

Walker’s Point, where both of Paul’s recent theaters have projected, and the abutting Third Ward have had the most drastic commercial and residential activity in any area of Milwaukee proper since the early ’90s. For all the condos, boutiques, and open plan offices put up in that time, there are currently at least six of the same in some phase of development, plus your occasional world-class freshwater research facility. The other hulls of yesterday’s light industrial demands wear “FOR SALE” signs like necklaces.

Slowly but surely, this is a part of town that gets potholes fixed more quickly and cop calls answered immediately. The replacement of the offending alley light, that unending house light, is no intentional thorn against the theater, according to city leaders. Alderman Jose Perez has represented the area since 2012. It was late in the summer last year when Perez says he and city workers made note of the dead bulb in an annual patrol of nuisances large (“hot spots” of drugs or suspicious activity) and small (the alley light). While there was no complaint lodged on the darkness of the alley that housed the theater, Perez says not replacing it could have created a safety risk. Only after the replacement was screwed in did Perez hear about the theater’s existence, when calls by one of Dorobialski’s friends made their way up the chain to him from the Department of Public Works lighting division. There could be issues with permits or rights-of-way, but Perez says there may be a way for the lightbulb and the cinema to “coexist.” Frankly, Perez sounds charmed by the initiative behind an alleyway theater.

“Unless someone complains [about the theater], I’m not going to look into it,” Perez says. “I don’t want to be that guy.”

The typical first show of Paul’s season is the weekend of Good Friday. The last is Halloween. Jesus Christ Superstar and Rocky Horror Picture Show, respectively. These are both during optimal years, without the light pollution and creep of progress.

This week, the City of Milwaukee Department of Public Works released a statement on the matter with this offering, which is vague yet in the vein of what Dorobialski says he’s been seeking: “Because public safety is our number one concern, Ald. Perez and DPW representatives are willing to meet with Mr. Dorobialski to discuss his cinematic activities and any options going forward.”

There may be another solution, as per a separate update from Dorobialski. It’s not a message via Facebook—that’s run by his buddy and co-worker Mario, “The Sicilian,” as Dorobialski puts it in some Old World way. Dorobialski’s email is proud, with all the joy of a heisted MacGuffin:

“It caught everybody by surprise. Passersby didn’t know what to think. Someone I know put a reflector in the alley light, so no more ‘light spill’ where I didn’t need it. I ran The Maltese Falcon on Saturday night. One of the younger guys that stopped by asked if this was a ‘special event.’ I told him Paul’s Alley Cinema is special. He looked it up on Facebook [and] complimented on how I use rear screen projection. A young woman with her group complimented me on continuing to do the movies, that it adds to the neighborhood.”

The light situation may be resolved minus the bureaucracy. The city grumblings may still return or move on to another alley in the refreshed memory of urban development. As an outsider, you’d be excused for forgetting about the cinema, if you’d ever heard of it, given your other considerations of Netflix and chilly weather, of gallery nights and daylong pub crawls. All the same, Paul Dorobialski, the city’s last renegade cinema showman, sounds like he might be back on the big screen, projecting whatever seems right, just to get away with it, on a slab of lost city theater screen draped in an alley begging to give in to time.

Paul’s Alley Cinema will screen 1963’s Gypsy this Friday, at dusk.