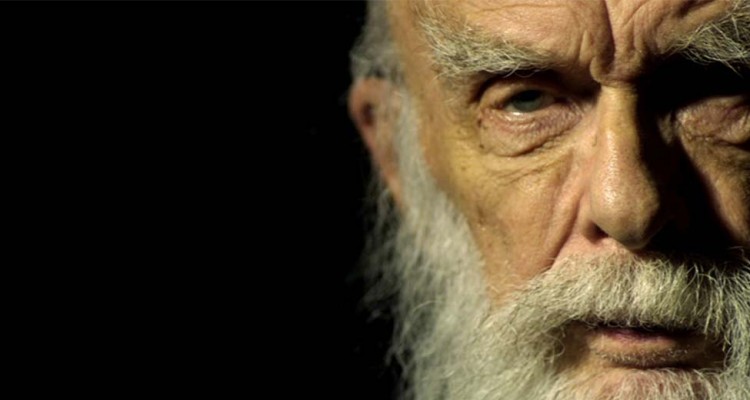

James Randi originally chose “The Amazing Randi” as a stage name back when he was plying his trade as a magician and escape artist; little did he know it would nicely sum up his entire seven-decade-and-counting career. After dropping out of school at 17 to join the carnival, Randi began modeling his life on his idol, Harry Houdini. International success soon followed, but it was Randi’s second act as a dogged debunker of all things supernatural and paranormal that truly made him a star. His protracted and public battle with “psychic” spoon-bender Uri Geller was as eye-opening as it was entertaining, and his takedown of slimy faith healer Peter Popoff was an example of gonzo investigative journalism at its finest. (With the help of an undercover electronics expert, Randi discovered Popoff’s direct link to God was actually a radio-equipped earpiece, with his wife feeding him information on the other end.) In more recent years, he has become something of a patron saint, if you will, of the skeptical community, and has inspired the likes of Penn & Teller and MythBusters’ Adam Savage, among many others. All that and more are covered in the highly entertaining documentary An Honest Liar, a fleet-footed primer on Randi’s life, and an unexpected document of a deception at the heart of his personal life.

At 86, it would be easy to forgive Randi for slowing down and taking things easy in his Florida home, but he remains as busy, lively, and irascible as ever, continuing to oversee his James Randi Educational Foundation, prepping for the next “Amazing Meeting,” and touring in support of An Honest Liar. Before Randi and co-director Tyler Measom visit the Milwaukee Film Festival for a screening of the film Sunday, October 5, 4:15 p.m. at the Downer Theater (the film also screens Friday, October 3, 7:15 p.m. at the Downer), Milwaukee Record spoke to the pair about the fine art of deception, handwritten letters from Johnny Carson, and mud wrestling with Uri Geller.

Milwaukee Record: Randi, in the film you describe a moment early in your career when you realized you could use your skills as a magician to become a con artist, or use them for good. What is it about your background that makes you qualified for the path you ultimately chose?

James Randi: As a magician, I have a handle on secrets and confidences of various kinds, because that’s what the whole profession is based on: we’re doing tricks, we’re deceiving people. But we’re doing it for purposes of entertainment. By the exact same qualifications, anyone who acts and does Shakespeare, for example, and plays the part of Hamlet, is also lying to the audience. That’s not really the Prince of Denmark with the blond wig onstage. So it’s not too unusual in the entertainment business to have people who are lying to you. They do it for purposes of entertainment and your delight, and we hope for your information as well. So as a magician, I’m very well experienced in keeping secrets and using secrets in such a way that nobody will be able to solve how I’m actually doing what I’m performing on stage.

MR: Do you still see yourself as a magician today?

JR: That’s my profession, my discipline. I try to use it nowadays as a way to inform people and to wean them away from dependence on people out there who are going to take their money, and their sanity in many cases. And certainly their futures if they will allow them to do that by lying to them, and by telling them they have actual magical powers. I know how these things are done. I recognize what they are, and I’ve always recognized them ever since I saw them as a teenager. I’ve always resented people who will stand before people and tell them that they’ve got real supernatural powers. I don’t believe in it.

MR: One of your most famous investigations was when you revealed Peter Popoff to be a fraud. He went into bankruptcy soon after that, but he’s still around today, doing the same shtick. Is it discouraging when people like Popoff or Gellar don’t simply disappear after you expose them?

JR: To a certain extent, yes. I’m disappointed that people out there don’t really watch and listen and think about the facts that they’re presented with. When it came to Popoff, it seems that no one who followed him before gave him up at all. There were a few people who located me somehow and told me, “Oh yes, I will NOT go to Peter Popoff…but there’s this fellow, Reverend so-and-so, and I’m going to give my money to HIM now!” So all they were doing was transferring their gifts over to the exact same kind of rascal as Popoff. They won’t learn, they don’t want to learn. They need the fantasy. They need some magic in their lives, and I was trying to take it away from them, so they felt.

MR: That brings up an interesting parallel to your Project Alpha hoax. (In 1979, Randi planted two amateur magicians, Steve Shaw and Michael Edwards, into a paranormal research lab and billed them as real psychics. Before it was publicly revealed to be a hoax, the investigators were fooled.) In the film, Shaw and Edwards express some guilt about pulling one over on people who so desperately wanted to believe. How do you grapple with the ethics of that?

JR: Well, something has developed since the film was made, as a matter of fact. The professor who had been taken in by a bit of a scam…Well, what we tried to do was send a couple of people to a lab disguised as psychics. They were clever kids, they knew how to fool the professors and whatnot, and they did exactly that. The plan all along was that we would eventually reveal the scam in order to teach the parapsychology community—and it’s very vast in this country and around the world—that they can be fooled. And they were fooled in this particular case. It was a good experiment. It worked very well.

Now you would think that the gentleman in the charge of the lab who had been taken in by it, you would think that he would have recognized that fact. But we found out just recently that he’s made statements to the effect that the boys really were psychics, and they really could do these things. You cannot convince somebody who has so much hanging on a premise or an infatuation that is important to them.

MR: Tyler, how did you first become involved in this project? Were you a fan of Randi going in?

Tyler Measom: A few years ago, I had finished my other film, Sons Of Perdition, and of course you’re always looking for the next project. Everyone’s always asking you, “What are you going to do next? What are you going to do next?” And then, instead of asking me, somebody said to me, “You know who would make a good subject? This man James Randi.” I was vaguely familiar with him, but it took me about an hour-and-a-half of research before I thought, “Oh my God, I can’t believe no one has made a feature-length film about James ‘The Amazing’ Randi!”

So I reached out to the James Randi Educational Foundation, and after a couple of months of convincing, they said, “Yes, we want you to make the film.” So I flew out to Florida and met with Randi. And then my partner Justin [Weinstein] and I, whom I met at a film festival, we dove right in headfirst. That was June of 2011, so we’ve been going for more than three years.

MR: Speaking to that length of time, An Honest Liar takes an unexpected personal turn midway through the film. How did you deal with that as filmmakers?

TM: Our intent was always to use the medium of documentary in a way to fool the audience, much like Randi does with magic. We always wanted to go into it with a little bit of, “How can we pull the wool over the eyes of the viewer?” One of the motifs of the film is “Be careful.” Don’t trust everyone. Don’t trust the media. Don’t trust psychics. And maybe you shouldn’t trust documentaries all the time, either.

What happened was that Randi’s partner, Deyvi [Pena], was involved in an incident that really turned the film into a different kind of movie. Not only did that extend the filming of it, but it also made the story a bit more interesting, and in some ways more difficult to tell.

MR: Randi, after that incident comes to light, there’s a scene in the film where you seem hesitant to continue. Were you really thinking about pulling the plug on the project?

JR: At the point I had made that comment, I was quite sincere, but I had just recently been exposed to the problem that had arisen. I hadn’t really thought it out and I was wrestling with it. It was quite serious, as you’ll know after seeing the film. I reacted badly, I must say. I had made an agreement with the boys that it was going to be warts and all, as Oliver Cromwell said to his portraitist. I had to go back to that. It was a matter of a day or so. It wasn’t very long, I can assure you. I called back and said, “Okay, let’s go with it. We have to do it that way. That’s my agreement with you, and let’s handle it.” And we did. And I think we handled it very well.

MR: Tyler, I know running time is always a concern, but how did you decide what to include and what not to include in the film? There are fairly significant episodes in Randi’s life—the One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge, his spats with Sylvia Browne—that are barely mentioned.

TM: Obviously it wasn’t easy. It was a very difficult process. It was about a year—16, 17 months—of editing around the clock with our full-time editor, Greg O’Toole. When you start a film, you want to try and put as much in as you can, and then you realize some things have to get cut down. We’ve got 86 years of an amazing life. We’ve got hundreds of hours of archival footage. We’ve got at least 100-plus hours of footage of us following James Randi around. So it really became a question of what would the audience not know about. But more so it’s about telling a story. What is the best three-act structure? And within the film and the three-act structure itself, there are certain episodes: the Alpha Project, Popoff. Episodes that in and of themselves are stories.

JR: And of course hanging over the whole thing is the possibility that there can be sequels! You still have lots of material that hasn’t been developed.

TM: Yes we do! There were a lot of things that you wish you could include that were just small, little moments that we had to end up taking out.

MR: It’s great that you included as much archival footage as you did. Clips of Randi talking to Barbara Walters and Larry King, clips of him on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Randi, you had an interesting relationship with Johnny Carson, who himself was an amateur magician. Could you talk about that?

JR: It’s quite a complicated situation. I did a lot of shows over the years with him, and it seemed that every time I turned around I was being invited to do it again and again and again. There were many repeats of the shows that I did as well. There was a period for a couple of years where on weekends they would play another Carson show, so I got a lot more showings than I might have deserved.

But I must say that John was very, very generous with me. We hit it off very well. We were kindred souls in some ways, I’m sure. The proof of it was that John never wanted to meet any of the guests on the show before he met them on camera, out on stage in front of the audience. That was a standing rule with him. He was adamant about it. But the last four or five times I appeared on the show, he would come to my dressing room and tap on the door, and I’d open the door and the whole staff would be standing with their mouths open saying “But he doesn’t want to meet people!” He would just come in and quietly close the door and say, “Is there anything I should mention for you? Anything coming up that you want to announce?” He thought of me very much differently than he thought of a lot of other folks, I’m sure.

MR: The footage of Uri Geller completely choking on The Tonight Show because of changes you made to his psychic demonstration is incredible. I’m glad it made the final cut.

JR: Oh yes. We couldn’t have resisted that one. I think I would have had to wrestle the guys in the mud if they had tried to take it out!

TM: [Laughs] Uri Geller?

JR: No, I don’t wrestle with Uri Geller. I stay as far away as I can. [Laughs]

TM: We treated the Uri Geller and Randi storyline in the film much like a superhero and villain, if you will. Most protagonists and antagonists in a narrative are very similar. Every good superhero has a villain: Superman has a Lex Luthor, Indiana Jones has a Belloq. They’re both similar in many ways with their powers. They just have a slightly different way of using those powers. So I used that as a through-line in the film, that these two use the same powers, and came, for the most part, from the same place. But one chose the path of good, and the other chose the path of…I don’t want to go as far as “evil,” but chose the path of deception.

JR: I like that word, “evil.” What’s wrong with it?

TM: [Laughs]

JR: Gentlemen, I’ve got something on the wall in front of me here. It’s a framed letter. I got a lot of letters from Johnny Carson over the years, but this one, I think, is rather special. It’s all handwritten by Johnny himself. It reads this way:

“Dear James. After watching John Edward on Larry King last night, I was reminded of Bacon’s admonition: ‘A credulous man is a deceiver.’ On the gullibility scale, Larry is second only to Montel Williams. I hope the enclosed will help to educate them both. With great affection, my best, Johnny Carson.”

…I have a hard time reading that, really. But I must say, when you get a handwritten letter like that from Johnny Carson…it gets to you. You know that you’ve got a really valuable friend there. By the way, when I read, “I hope the enclosed will help to educate them both,” that was a very, very large check from Johnny Carson. He helped our foundation get off the ground, and he kept it going for quite some time. I was always very much appreciative of that, of course. The Carson Foundation still maintains a contact with us, and every now and then we get donations from them in the name of Johnny Carson. It’s very welcome to us, of course.

MR: It should be noted that Uri Gellar is interviewed in the film. There’s a moment when he claims that belief in the supernatural and paranormal is more popular today than ever, which proves that you’ve failed. How do you respond to that?

JR: Well, first of all, he referred me to The National Enquirer, so I don’t think his standards are very high. In any case, it’s pretty evident to me that Geller has…well, he has all the money in the world, I’m sure of that. But he met a nemesis in me, and I think I won that encounter, and I just ignore it now. I’m not going after him still. What’s the point of it? People know how he does his tricks now. They’ve all been exposed. They’re not magic. He likes to be known now as a “mystifier.” He used to be known as a psychic, but he’s now known as a “mystifer.” What the hell is difference? Do you want to be known as the Count of Monte Cristo next? Give me some other thing I can get my teeth into, please!