Awful, awful news for fans of local public television and hypnotically watchable auctions: Milwaukee PBS plans to drop its long-running Great TV Auction, which has been a delightfully homegrown staple since 1969. This awful, awful news comes courtesy of a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article that details the station’s new strategic plan to create more local programming and get in on the sweet, sweet 2020 Democratic National Convention action.

But Milwaukee PBS’ strategic plan also includes some addition by subtraction — specifically, the Great TV Auction. The TV auction that aired in May will be Milwaukee public TV’s last.

[…]

“It’s the kind of activity that’s terrific” for connecting with viewers, [Milwaukee PBS General Manager Bohdan Zachary] said. “But at the end of the day, when the economics are showing something else, there’s no denying that.”

The piece notes that “a review of costs and revenues showed the auction generated a net loss.” Ugh.

In memoriam of the Great TV Auction, here’s a piece we published in 2017. Oh, and let us know when someone sets up a Change.org petition. R.I.P.

I WATCHED 8 HOURS OF THE MILWAUKEE PBS GREAT TV AUCTION

By Kevin Mueller

If you haven’t noticed, it’s springtime in Milwaukee. Trees have begun to blossom, the hardened blocks of snow pushed from plows into parking lots have finally thawed, and, at the moment, it won’t stop raining (oh, and there was a pretty awesome local music festival last weekend, too). But to me, this season of renewal has come to bring about only one thing: the finest event on the local television calendar, the Great TV Auction.

This annual tradition, now in its 49th year, serves as a fundraiser for Milwaukee PBS, a cash-generating campaign that helps bankroll the budget for national and local programming. Its cadre of syndicated cooking shows and small-town delights like Around The Corner With John McGivern couldn’t exist, as they say, without viewers like you.

While many people grumble when on-air benefits interrupt regularly scheduled programming, the Great TV Auction is actually one of the most watchable programs the station produces. In years past, I have become absolutely fascinated by the show, getting sucked into watching for hours at a time. I catch myself shouting “Overbid!” after a three-hour binge where my shirt is stained with Cheeto dust, an empty pizza box lays on the floor, and my ego has experienced irreparable damage.

To get a true understanding on the insatiable magnetism of the program, I set out to do something (not-at-all) brave (and actually quite pointless). I watched an entire eight-hour block of the Great TV Auction. Here’s what I learned.

“We’ll show you an item. You bid on it.” That’s the opening host explaining the straightforward rules of the auction. Viewers are encouraged to call in and place bids, starting at $10. An estimated value for each item is provided for perspective. The bidding closes on each table after about 10 minutes. By that time, they have already shown another table of goods.

Hosts cycle in and out every two hours or so. They’re in charge of keeping the action flowing but often find themselves mitigating some disaster—either trying to make sense of a mix-up in copy or figuring out what table to throw to next. “Table A is closing in three minutes,” a host says. “Table X!” is shouted from off-screen. “Oh, Table X is closing in three minutes. And now let’s see what’s at Table C,” the host corrects. “Table A!”

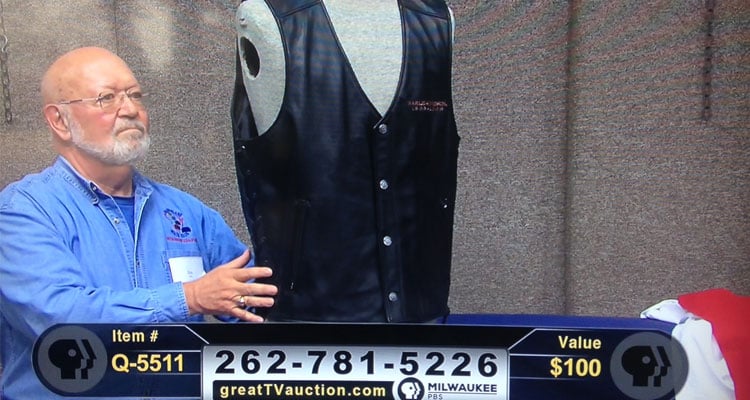

The auction itself moves quite swiftly, which most likely generates the constant confusion. The host throws to someone standing at a table full of biddable items and this person goes through these eight items with a guest “table captain”—usually a volunteer plucked from answering phones and put in front of the camera. While the former reads flowery pre-written copy on each item (the word “arresting” is invoked excessively here), the table captain models each offering, usually running their hands along the edges of the item. But sometimes the model engages in more cavalier gestures like caressing or pointing, and in extreme cases, accidentally knocking the item over.

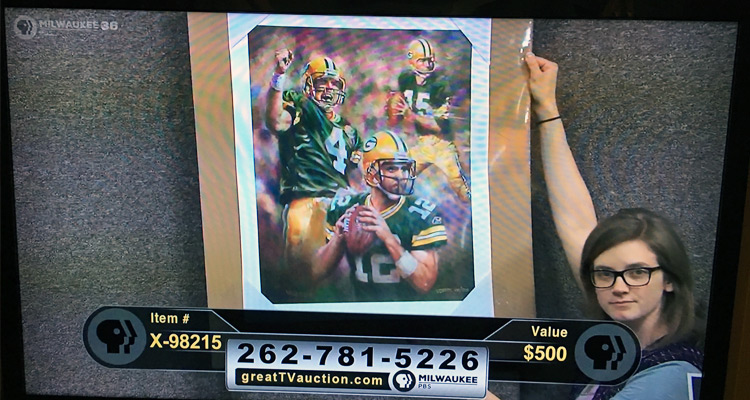

The options range from staid art prints to chiropractor sessions to Sprecher hard sodas to single episode DVDs of the aforementioned Around The Corner With John McGivern (estimated value: $15). “A trio of wolves, one of them is calling for more meats,” a table host sight-reads from a piece of paper, detailing the one of many wolf paintings seen throughout the day. But if there’s one category that keeps MPTV afloat throughout the year, it’s Green Bay Packers merch. About every other table features some gaudy print of Aaron Rodgers, Clay Matthews, and Jordy Nelson. It was created for the auction by a featured artist and each copy of the 100-made prints is given an estimated value north of $200. Almost every time the print appears on a table, it rakes in more than the assessed worth.

The show is an “arresting” showcase of eccentric characters, trite art pieces, and many, many blank, uncomfortable stares directly into the camera. It’s like watching something from the Found Footage Festival—except, of course, you’re watching all the madness unfold live.

Murphy’s Law cycles at a rapid-fire pace on the Great TV Auction. (Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong about every 15 minutes). That’s really what keeps you going after watching eight straight hours of this perpetual process. When you can’t stand looking at this glowing screen for one more table, a crew member is too eager to pull down a print, the camera lingers on the mishap, and it’s the funniest shit ever.

I had to stop watching at some point—the show only airs from 3-11 p.m., thankfully. At the end, I was exhausted and relieved and somewhat surprised that I made it from sign-on to sign-off. The following day I tried but couldn’t bear to watch more than a couple hours. Even though I was burnt out, I got the feeling that I was missing something extraordinary. Was there an overenthusiastic and gaudily dressed table captain that I needed to see? Did a table accidentally fall over? How many times did they say “arresting”?

I couldn’t help but feel miserable about all of this. Here are nice people—volunteers, even—offering their time to save the untenable future of public television, trying with all their might to produce good live television. And all I cared about was finding humor in their disarray.

Somehow, watching this ungodly amount of the Great TV Auction forced me to discover the humanity in these people. I now find myself wanting them to create the greatest show possible, bereft of errors, in order to avoid the cynical laughter of viewers like me. I want the transitions to be smoother; I want the copy to be read more easily; I want the production to be pristine.

This all left me with one lasting conclusion: I’m going to volunteer next year.