Say what you will, Bob Dylan is a worker. After touring almost nonstop for more than 30 years as part of his “Never Ending Tour,” he announced a slew of dates named after his acclaimed 2020 album Rough And Rowdy Ways. “The Rough And Rowdy Ways Tour” first kicked off in Milwaukee in September 2021, and it’s set to continue through 2024. That’s a lot of performances for an 82-year-old who has never stopped rambling, never stopped restlessly exploring his art or the traditions that inform it.

There is no resting on laurels in Dylan’s career—hell, there isn’t much resting. With a Nobel Prize, another biopic about to be released, an ever-expanding cottage industry of critics, commentators, and speculators fixed on his varied oeuvre and mysterious persona, as well as the fairly recent opening of a Bob Dylan cultural center and museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, there have been plenty of laurels for Bob to avoid.

Bob Dylan might be a lot of things, but he is no mere legacy act. “I’m last of the best / You can bury the rest” he coyly snarls in “False Prophet,” a song performed with an off-kilter swagger at The Riverside Theater Thursday night, one of nine songs from this latest album of original material included in the hour-and-45-minute setlist. For Dylan to have such a range of classic songs in his back pocket—many of which have become universal cultural touchstones—and to still stick with populating half of the set with songs from his newest album demonstrates the degree to which he may have finally painted his masterpiece—or at least one of them, and he knows it.

The specter of Dylan’s 2021 shows loomed large over Thursday’s performance. Those shows featured unusually sparse arrangements for Dylan—the gentle swells of lap steel and a muted restraint from his band—that allowed his voice to carry the songs. It was as if after years of loud, raucous rock bands behind him, Dylan had refocused on the key to his connection with audiences: that singular, unique voice.

And while his voice was in excellent form Thursday night, both razor-sharp and dynamic in its sometimes almost be-bop phraseology, it was the arrangements themselves that gave the songs their anchor and their stately grandeur.

On the last tour, several Dylan fans seated nearby informed me, Dylan played primarily at the piano. But his playing was more in line with embellishment: rolls, frills, sparse chord clusters, single note melodies. This time around, Dylan had again re-framed even his new songs with a different emphasis of stylistic historical reference: barrel house, boogie-woogie, and early proto-rock ‘n’ roll. Dylan’s piano playing came even more to the fore in the excellent audio mix at The Riverside. The arrangements overall gave a more powerful rhythmic emphasis, more drive and force to contrast with the moments of hushed sublimity in songs like “Mother Of Muses.”

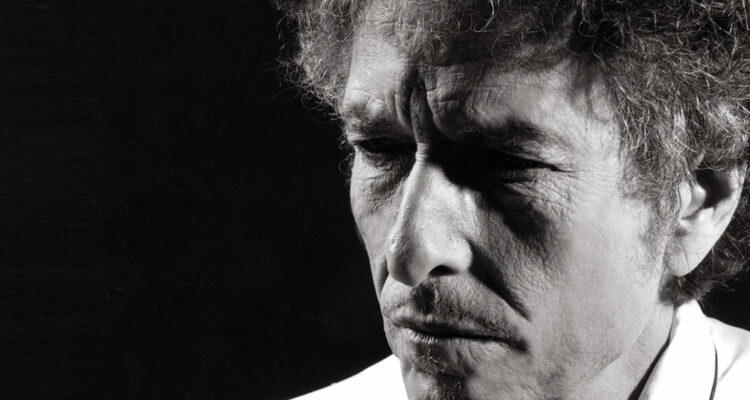

Dylan appeared at the piano in a white Stetson porkpie hat, a fitting prop, right out of the old folk standard “Stagolee.” The band opened by launching into “Watching The River Flow” with buoyancy and humor—one of a series of songs selected for the set, and played throughout this tour, that could scarcely be called one of the “heavyweights” in Dylan’s long songwriting career. At moments pounding the keys like Fats Domino (as on “You Go Your Way And I’ll Go Mine”), Dylan sometimes created a wall of cascading chords for the other musicians to bounce off with subtle rhythmic variation and interplay, with which he could ride the songs with a sense of ease and grace, allowing his voice to fluctuate in dynamics, to croon, then whisper, to say and do things that great lyrics alone can’t.

Bob Dylan was in Little White Hat Mode this evening in Milwaukee, Wisconsin pic.twitter.com/gt2FE63HW9

— Jokermen (@JokermenPodcast) October 13, 2023

Throughout the sets, both Wednesday and Thursday night, Bob turned to songs from his back catalogue that some critics might call “fluff,” at least, compared to the lyrics of songs like “It’s All Right, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” But hearing “To Be Alone With You,” or “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” played with such felicity, such conviction, one questions their slightness, and realizes that songs are vessels to inhabit, that these re-imaginings give them a weight and impact that self-consciously profound and dense lyricism can’t, and that, after all, Dylan’s stylistic range is startlingly wide, even if his vocal range isn’t in a conventional sense. These older songs emerged as relics from a honky-tonk after-hours, sung at times in the manner of a country crooner like Ray Price, but with Dylan’s particularly sensitive gift for nuanced phrasing, transforming them into yearning pleas for intimacy and security.

People heading to the lobby or restroom froze in the aisles at “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” another song that Dylan isn’t particularly famous for. But its stately grandeur, with notable touches of Appalachia in its tasteful guitar flourishes, and vocal phrasing made it feel like an Ars Poetica of sorts, a consistent song in Dylan’s recent sets that seems to sum up what his art is doing, what it is about.

As has often been enumerated, sometimes bemoaned, and in keeping with his mercurial, restless, and at times seemingly contrarian nature as an artist, Bob Dylan doesn’t treat his old songs as static, fixed set pieces. There have not been, for many years, sets of “greatest hits.” But what is particularly distinctive is that he doesn’t treat his newest material with fixed or static song-structures either.

That was the glaring distinction of Thursday’s show: the newest songs had also met that shifting template of traditional styles that has revealed itself to be a hallmark of Dylan’s amorphous artistry. Nothing sounded like the record, something Dylan fans have come to expect and celebrate, but to the casual listener, something to consider as a conscious element of Dylan’s craft. Altering arrangements might be something performers dabble in throughout their careers, but with relatively new material, and to this often drastic degree, it’s an anomaly.

As the set rolled on you started to get what is one of the most commonly overheard comments at Dylan shows for years and years: “Wait…is this….? Oh, I guess not.” But once this ingrained desire to hear a performance replicate the recording is let go, the songs open up to become something akin to archeological digs—but not for bones, maybe for the spirits of thinkers and dreamers, of artists and entertainers past. Pieces of a puzzle that fit, but a puzzle too big to see the whole picture.

In his performances as well as songwriting, everywhere is reference, everywhere is lexicon. Shades of Big Bill Broonzy, Otis Spann, and Muddy Waters, were recognizable in the arrangements. “Crossing The Rubicon” went from the start of an epic hero’s journey, framed within something of a John Lee Hooker homage, to an ominous juke joint downbeat. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” went from the deep Delta to hints of a Kansas City shuffle. A highlight from the previous legs of the tour, “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You,” went from being an intoxicating and moving doo-wop-inflected waltz about love, duty, and vocation to reminding one of the sweetness and earnestness of a swinging Sam Cooke number.

The band also strategically employed touches of that muted restraint that have made the 2021 leg of “The Rough And Rowdy Ways Tour” already legendary. A highlight that evoked this spectral quality and brought together disparate strengths of Dylan’s current band was the arrangement of a particularly foreboding “Black Rider,” both propulsive and vexing in its musical suggestiveness. It’s a song much like Dylan’s own “Man In The Long Black Coat” or the traditional “Black Jack Davey,” a song that engages with the misdeeds of a mysterious stranger in town and evokes the ever-present specter of death, loss, and evil. The narrator of this song can perceive the patterns of fate in the chaos that surrounds them. It’s a song that belongs to a tradition of balladry much older than the instruments that made it come so hauntingly alive Thursday night.

Consider “Key West (Pirate Philosopher),” a long dreamlike evocation of some palpable Elysium—not just a retirement, but a place where a scavenger narrator recites a collage of lines from cultural history. “McKinley hollered / McKinley moaned / Doctor said, McKinley, Death is on the wall / Say it to me, if you got something to confess…” “Key West” has been one of the new songs most drastically changed in arrangement, always feeling like it is attempting to arrive somewhere. Sometimes it does, with sublimity and mystery, sometimes it is simply an interesting journey. Its lyrics also mimic an aspect of Dylan’s overall artistry: “I’ve played both sides against the middle / Trying to pick up that radio signal.” It is a constant searching that the song enumerates and embodies, a search for its actualization. On Thursday, the arrangement and Dylan’s phrasing felt rushed, too quick in tempo for the vast sentiments it embodies, the expansiveness it suggests. But maybe it is headed somewhere. It feels like that could be, too.

Throughout the set, Donnie Herron’s fiddle and Bob Britt and Doug Lancio’s guitar interplay were not creating a sonic aether for Dylan’s voice to emerge from, at least not in the ways they have on other legs of the tour. Instead, they were employed with intentionality to give emphasis and lift to what are (one forgets) quite long songs. As always (and for decades now), bass player Tony Garnier was an anchor, obviously a musician of such skill and adroitness that he has become the de facto band leader who can anticipate the sudden changes and idiosyncrasies that make Dylan such a dynamic performer. But this time around it wasn’t just about Bob’s voice; this time it was about the structure and rhythm of the songs.

The band closed with “Every Grain Of Sand,” and the only appearance of Dylan’s iconic harmonica in the set. I’ve heard Dylan detractors refer to his harmonica as a “wailing space-filler,” but it was a captivating, melodic, and mournful harmonica solo. It ended the night with the sense of humanity and frailty behind the spirits that animate Dylan’s songs.

After the show, at a local pub, I sat in on something of an unofficial Dylan summit. I was accompanied by bonafide “BobCat” Sam Taffel, a filmmaker and performer. We sat down with two prominent Dylan fans, music writers, and podcast hosts who had never met in person before: Steven Hyden and Ian Grant, who along with Evan Laffer, together host a podcast focused on the nebulous world of unofficial live bootlegs of Dylan shows. Their podcast is called “Never Ending Stories: Bob Dylan & The Never Ending Tour,” and for a Dylan fan, even a casual one, the revelation of dissecting and examining the different permutations of songs in a live setting over several decades gives an entirely new dimension to what it is Bob does that’s “such a big deal.”

I asked Ian, who is also the host of “Jokermen,” a podcast that focuses often on Dylan’s later career work, about his standout impressions after having seen and listened to so many Bob Dylan shows. “He’s always doing something different, always experimenting, obviously,” he said. “But tonight’s show felt more, I don’t know, muscular, more forceful, than in 2021. It had more swing, more bounce, more rhythmic emphasis and variation. This might be partly because of the brand new drummer, Jerry Pentecost from Old Crow Medicine Show. He seems to really pick his players with intention.

“The songs felt solid, material. They were often groovy,” he continued. “Whereas I think in 2021 and 2022 they felt like they were materializing out of an ether. This feels like they’ve arrived, or maybe are still arriving.”

Hyden is something of a live bootleg connoisseur, and is the author of the liner notes for Dylan’s Fragments: Time Out Of Mind Sessions. For him, a highlight of the show was a nod to one of Bob’s beloved peers.

“‘The Rough And Rowdy Ways Tour’ band have been working Grateful Dead covers into their sets for a few years fairly consistently now,” Hyden said, “but it really warmed my heart to see him turn to Doug Lancio and say, off the cuff, ‘Let’s do “Truckin’.”‘ It was a beautiful version, and pitch-perfect for that spot in the set. I love seeing Bob suddenly inspired to do something, in real time, and then it works out just right.”

The breadth of the musical and lyrical reference in these songs isn’t always exactly the “hip” kind. These are songs, even when lighthearted, that seem aware of the historical dialogue they are having. And while the arrangements are dynamic and new, one realizes slowly they are watching “folk tradition” enacted in the songs’ constant evolutions, changing tempos, keys, even mood and meaning, through a succession of various permutations and styles. Granted this is something Dylan has done in varying degrees throughout his history as a performer, if not as a recording artist. He lets you observe him as an artist, real-time, while developing and learning, interpreting and reconstructing his art organically over the past several decades. There really hasn’t been anything quite like this in popular music history.

An artist who produces so much material is bound to be inconsistent, but Thursday night’s show at the majestic Riverside Theater was the perfect atmosphere for Dylan’s new sound, and the perfect atmosphere to revisit a constant revelation: that we are lucky to be alive to witness such an artist, in his autumn years, still this engaged with being new inside of traditions that are so ancient, so archaic. And we all concurred that we once again felt lucky to be able to watch Dylan still watching the river flow. What a wide and deep river it is.

Want more Milwaukee Record? Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter and/or support us on Patreon.

RELATED ARTICLES

• Bob Dylan will play two nights at Riverside Theater, October 11-12

• Some questions (and answers) for last night’s Bob Dylan show at Riverside Theater