It’s a rainy Thursday night on the long, commercially dilapidated stretch of highway that is Layton. I’m driving around in my black jeep, my rideshare app turned on. I’m cruising up on St. Luke’s Hospital when I get a ping. It’s from “Meccah.” No, it can’t be.

I pull up to the emergency room entrance and out he comes, walking with that confident hunched saunter of his. When I see the baggy military pants and timbos, I know its definitely him: Meccah Maloh. He gets in and I call him by his government name. He asks me “Does it say that name on the app? How did you know that?” I tell him who I am and he recognizes me, and we start catching up.

“Brooo, I thought I had the coronavirus!” he says through his medical mask.

Luckily he doesn’t have it, otherwise I might not be here. Our conversation steers towards pasties, dough pockets filled with a type of chunky ground beef and potatoes. I ask him about the pasty shop on the north side. Meccah, like many people who grew up on the north side, went their whole life eating the treats at Reynold’s Pasty Shop (3525 W. Burleigh St., 414-444-4490). I was also a north side kid, but my family spent most Sundays on the south side and we had our own famous treat spot, a custard place I would rather not name. He gives me a lot of information that isn’t on the website. They have frozen ones in the store, but there’s nothing like having one directly from the shop. This along with an important piece of advice: Always go for the gravy.

It’s 11 a.m. when my niece and I make the trek up Fond du Lac to 35th and Burleigh. The turnoff towards the shop is like being in a particularly difficult level of Sonic Spinball, but that’s okay. On a small block, above a heavy wood and glass door, sits a white sign with bold red lettering that just reads “THE PASTY SHOP.” There is bright neon in the windows. Between a Boost Mobile and a nondescript tan building with a metal shutter door, it is one of only three places you can enter on the small stretch of jutted concrete.

Immediately I am greeted by the smell of pepper, starchy dough, and beef stock. The lobby/ordering area can’t be more than 20-by-20 feet, and it looks like not much has changed or has been switched out since the place opened in 1956. There is wood siding on the inside, the kind you would find in any Midwest basement in the ’70s. Posters, local ads, and homemade flyers pleading with you to “Have a pasty and not some drugs” adorn the walls, peeling slightly at the corners.

The most modern part of the shop is the menu, a brightly colored light-up plexiglass box above the main ordering area. I have seen this same box in many of the cult eateries I have been to in America, mostly in barbecue shops in the South. They make ordering easy while not disrupting the essential character and spirit of the locale. They serve but one thing here: pasties and every stage of them.

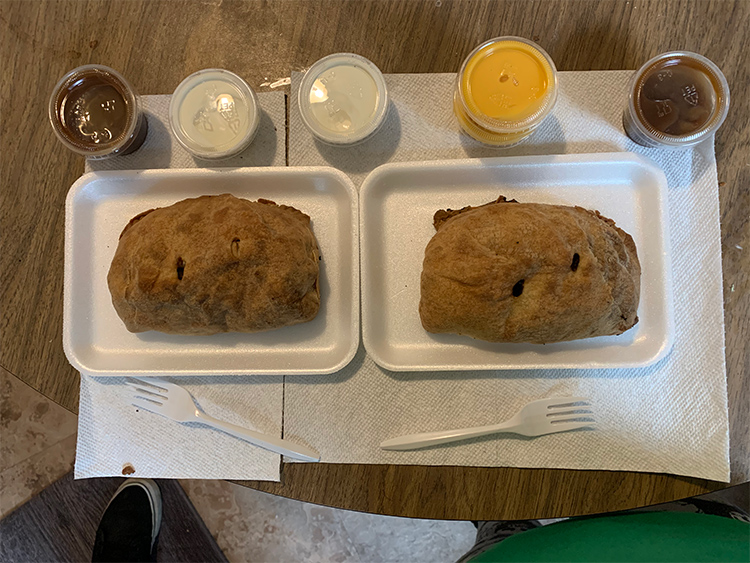

There are par-bakes, which you can take home and bake yourself. There are broken pasties, day-old pasties, and pasties by the dozen. The broken and day-olds cost slightly less but are all in the neighborhood of $4.50 and below. A fresh and unbroken one will be $4.65. They have sides that come in small plastic containers.

I ask for one of each. Hot nacho cheese, hot brown gravy, sour cream, and pickled jalapeños. I order two, and there is no place to sit and eat, so they give us plates and forks in our to-go bags. Latrice, the woman working the counter, tells me that it is a slow Saturday. “Usually we have sold about 100 pasties by now, but I think people are afraid to come out right now with the virus and all.” Indeed, but the man in front of me wasn’t afraid to come out to get his pasties and argue with one of the cooks about whether Diana Ross or Donna Summer was sexier in the ’70s.

To say this place has a charm to it is a criminal understatement. My friend Alicia tells me that it’s not just about the pasties, but how it is exactly the same as when she first came as a child in the 1990s. There are few places like this in Milwaukee. The ones that will not bend to new, fast-paced concepts. It is not about being stubborn or refusing to adapt, but if it’s not broken, why fix it?

[Editor’s note: A call to Reynold’s on March 25 confirmed that, yes, they are still open for takeout.]