Every Fourth of July, Americans take pause to recognize the selflessness and sacrifice of those who have put their life on the line for their country. Countless servicemen and servicewomen from Milwaukee have fought and given everything to uphold America’s independence, including a Bay View-born Air Force captain named Lance Peter Sijan.

Half a century after his death in a North Vietnamese prison camp following horrific injuries, unimaginable hardship, and unspeakable torture, Sijan’s name and heroics are still as remarkable and important as they were in 1968. For those who knew the Medal of Honor recipient during his brief-but-brilliant life, the love and legacy he left behind are just as special as his bravery in battle.

NOVEMBER 9, 1967 – JANUARY 22, 1968

On November 9, 1967, then-13-year-old Janine Sijan (now Janine Sijan Rozina) answered a knock at the door of her Bay View home and saw two men from the United States Air Force. Her life would never be the same.

“In a very naive state at 13 years old, I thought that was good news. I looked out and started to open the door. My mom had come to the staircase and I called up to her and said, ‘Mom, there’s two Air Force men here,'” Sijan Rozina says. “As soon as she heard that, of course, she knew that would not be good news. She caught herself on the banister and went down to her knees. I immediately knew that something was not right.”

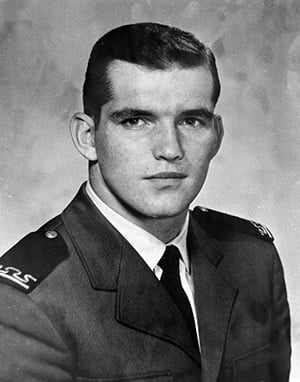

The family was informed that Janine’s 25-year-old brother Lance—a 1965 Air Force Academy graduate who had been stationed in Vietnam since July 1, 1967—was in an F-C4 Phantom II aircraft that went down. No beepers were heard and no voice contact was made. “That means they didn’t really know the outcome of his aircraft going down,” Sijan Rozina says.

The family was informed that Janine’s 25-year-old brother Lance—a 1965 Air Force Academy graduate who had been stationed in Vietnam since July 1, 1967—was in an F-C4 Phantom II aircraft that went down. No beepers were heard and no voice contact was made. “That means they didn’t really know the outcome of his aircraft going down,” Sijan Rozina says.

According to her, what followed was one of the largest rescue missions in the history of the Vietnam War. She says a total of 102 aircrafts were sent out to find the young Air Force captain and bring him back to safety.

“They made voice contact with him and they hovered in a helicopter above him for 33 minutes,” Sijan Rozina says. “They dropped down a line, and normally a [para-jumper] would jump down with it to go rescue him. [Lance] said, ‘Negative, I’m surrounded by bad guys.’ In essence, that statement condemned him.”

Unable to retrieve him, American forces left Lance. They returned the next day, but were unable to contact him. Unbeknownst to anyone, Lance had sustained serious injuries when his plane went down, including a skull fracture, a badly mangled hand, various cuts and contusions, and a fractured left tibia that protruded through his skin. Unable to walk, Lance crawled backwards, using his elbows to pull him along the jungle floor. He did so for 46 days, subsisting on—according to Malcolm McConnell’s biography about Sijan entitled Into The Mouth Of The Cat—plants and bugs, until he passed out on a road and was found by North Vietnamese forces on December 25, 1967.

“Forty-six days, he pulled himself through the jungle,” Sijan Rozina says of her brother. “He went in 220 pounds. By the time they captured him on Christmas Day, 46 days later, he was 80 pounds.”

Lance was brought to a temporary holding camp. He was emaciated, badly injured, and dealing with infection from leeches and rats, but he remained focused on getting home. Once left alone with a guard, he knocked out the lone man and escaped into the jungle once more. Though virtually immobile, he wasn’t found until hours later—at which point he was brought to a temporary holding camp in Vinh and tortured while awaiting transport to a Hanoi prison camp.

Lance was brought to a temporary holding camp. He was emaciated, badly injured, and dealing with infection from leeches and rats, but he remained focused on getting home. Once left alone with a guard, he knocked out the lone man and escaped into the jungle once more. Though virtually immobile, he wasn’t found until hours later—at which point he was brought to a temporary holding camp in Vinh and tortured while awaiting transport to a Hanoi prison camp.

On January 1, 1968, Lance and two other American prisoners of war, Guy Gruters and Bob Craner, were put in the back of a truck and sent out on a grueling five-day journey to the Hanoi prison camp—which became infamously known as “Hanoi Hilton.” Sijan Rozina says one P.O.W. would cradle her weakened brother as the other tried to manage the 55-gallon drums of gasoline that were rolling around the truck. “One guy would try to hold the barrels while the other held Lance,” Sijan Rozina says.

All three servicemen survived the arduous journey, but their struggles were just beginning. The young captain and his counterparts endured severe beatings and unthinkable torture. Though his body was diminished, Lance’s resolve was strong. He never gave up any information except name, rank, and serial number. Within days, he contracted pneumonia. Sijan Rozina says Lance lost consciousness on January 19 and died January 22, 1968.

LIFE WITHOUT LANCE

Of course, Lance’s little sister, his parents, nor anyone else knew anything about his whereabouts or his condition.

“The last thing we heard was that in 1967, they talked to him and then they left,” Sijan Rozina says. “We didn’t know. Is he a P.O.W.? Is he dead? Is he in the jungle? We didn’t know. From 1967 to 1973 when the war was over, we don’t know anything. We’re just trying to live.”

As the war waged on, Sijan Rozina was a teenager who “just wanted [her] family back.” With no knowledge of her brother’s death in early 1968, she and her family had no choice but to forge on and hope for the best in the years that followed.

“Your life just kind of gets put into a position that—you go between extremes of optimism and sheer desperation,” Sijan Rozina says. “Our family fell apart. We were all so devastated that we lost the brightest light in our family. Everybody goes through it differently, and you want remain hopeful that something’s going to happen and he’s going to come home.”

She says the family bought Christmas presents for Lance every year in hopes he’d return in time to open them. As instructed, they sent boxes to Hanoi on the off chance they’d reach him in a P.O.W. camp. Finally, in 1974—a year after the Vietnam War ended—they got some information.

“Once, we got a box that we had sent that had a cross [through Lance’s name] and said ‘deceased.’ We didn’t know what that meant,” Sijan Rozina says. “We still don’t know what happened. After the war was over, a list gets published by the North Vietnamese that says Lance was a P.O.W. and died in ’68.”

Sijan Rozina says that the North Vietnamese apparently had such a high level of respect for Lance that they buried him in a grave with a headstone that was engraved with his initials and the date he died. After the war, they agreed to send his remains and his headstone back to Milwaukee in 1974. A replica of that headstone can be seen at his new burial site in Arlington Park Cemetery in Greenfield. Along with his remains, the family also started to receive details of Lance’s final days from P.O.W.s who knew him and from others who’d come to learn about his courageous acts.

Sijan Rozina says that the North Vietnamese apparently had such a high level of respect for Lance that they buried him in a grave with a headstone that was engraved with his initials and the date he died. After the war, they agreed to send his remains and his headstone back to Milwaukee in 1974. A replica of that headstone can be seen at his new burial site in Arlington Park Cemetery in Greenfield. Along with his remains, the family also started to receive details of Lance’s final days from P.O.W.s who knew him and from others who’d come to learn about his courageous acts.

“The details of the story were more horrific than anything that we could’ve imagined, and the rest of your life is painted with horrible images of someone you love,” Sijan Rozina says. “Of course, a piece of you goes through a place of guilt. What was I doing when that was happening to him? What could I have done?”

Captain Lance Peter Sijan was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Gerald Ford in 1976. Janine and her parents attended the ceremony. That same year, the Air Force Academy renamed one of its dormitories “Sijan Hall.” In subsequent years, the Air Force decided to call its highest leadership accolade the “Lance P. Sijan Award.” Malcolm McConnell’s 1985 biography, Into The Mouth Of The Cat, helped tell the world Lance’s story. Streets have been named in his honor, monuments were erected, and California Field—where Lance practiced during his days as an All-City end for Bay View High School—was renamed “Sijan Park.”

“A MILLION LITTLE MOMENTS”

Janine has been present at many of the dedication ceremonies and has been the honorary recipient of many of her sibling’s awards and accolades through the years. However, she says she it wasn’t until around 15 years ago that she decided to “become very proactive in maintaining his legacy.”

She said she had a variety of goals for ways to properly honor her brother. The first goal was to move the airplane monument that was dedicated to Lance at the now-inactive 440th Air Force Reserve to a new home. Last May, that effort came to fruition with the opening of Lance P. Sijan Memorial Plaza near General Mitchell International Airport at 5500 S. Howell Avenue.

Nine years ago, Sijan Rozina started working on a documentary about Lance. Sijan has been in production for six years. The documentary was just completed, and Sijan Rozina plans to screen it at various film festivals and is hopeful it will be featured in this year’s Milwaukee Film Festival. Between festivals, corporate screenings, and university leadership programs, Sijan Rozina intends to tell her brother’s story all around the world.

“I realized that I had strong voice, and I realized that my life had been built and designed to do this,” Sijan Rozina says. “I knew the bigger picture, I knew the greater understanding. For decades, I was still the little sister. He’s frozen in time at 25, but I’ll forever have this relationship where he’s my big brother.”

More than 50 years after his death, Sijan Rozina says she recalls “a million little moments” with Lance. She remembers when her brother, the senior class president and football standout, got the lead role in his high school’s production of The King And I, then asked if she could play a little princess. There’s the time he rescued her from being stung by bees and when he asked her to be his date to the Academy’s Formal Christmas Ball. With their 12-year age difference and a father who worked long hours to provide for the family, Janine says Lance was a father figure and a mentor to her. He was her hero before he was America’s hero.

“He was bigger than life and he paid attention to me. He loved me and he listened to me,” Sijan Rozina says. “There was something unique about our relationship. He was the single most influential person in my life.”

Now that their parents have passed away, Janine is the lone acolyte left to carry her brother’s light and to preserve the life and legacy of Milwaukee’s greatest military hero. Fortunately, she’s willing to share it with others.

“In this time where individual pursuit is attempting to replace the values of family, commitment, service, integrity, and honor, this story must be told,” Sijan Rozina says. “He became a beacon of light to people as they connected with him in his life, and 50 years later, we’re still talking about him.”