Last week, I was shown a photograph of Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. She is near the end, seemingly lost in Molly Bloom’s punctuation-less, sensual reverie, immersed in the flows and throes of memory and pleasure that finally submit to sleep. This is the famous soliloquy that transforms “no” into “yes.” It is the chapter of the “mountain flower,” the “sea crimson,” of “breasts all perfume yes and his heart going like mad.” Those familiar with the passage may imagine it as a sort of mirror to Marilyn and the inscrutable world within her mythologized body. Others may find a mesmerizing dissonance. But there are more—many more—photographs of Marilyn Monroe reading. A Google search yields 1,490,000 results. She reads American classics, scripts, plays, magazines, newspapers, and a self-help book called How To Improve Your Thinking Ability.

Search “Susan Sontag reading,” and the results fall one million short of Marilyn’s. I only found one photograph of Sontag reading a book, which she authored (In America). A search for “Toni Morrison reading” yields 758,000 results. There is one picture of her in the act of writing, but none of her reading. But we know Morrison reads because she wrote a book about it (Playing In The Dark). Sontag has written diary entries on the “unique and enormous experience” of reading, in which her consciousness, her body, and the book become one. She would go on to assert interpretation as a creative act. She wrote a seminal book on photography. In photographs, she is more often sitting in front of a bookshelf; reading is implied, not documented.

“Reading Women,“ Carrie Schneider‘s multimedia exhibit at the Haggerty Museum (January 21-May 22, 2016) consists of a four-hour single-channel film installation of women reading, a selection of photographic portraits taken at the same sessions, and an artist book with two essays followed by photographs of each book held open by its reader. The subject matter is inescapably problematic. One cannot avoid the fetishizing implications of a woman portrayed in intimate union with an object: Women who bike. Women who smoke. Women who shred. Women who sew. Women who read. There is an inherent and alluring implication of artifice in portraits of women alone, engaging themselves, a trope echoed in advertisements, as well as in some of the most resonant approaches to self-representation by female artists and intellectuals.

There is a general thirst to know what and whether Marilyn Monroe read. Articles include, “The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?”; “Marilyn Monroe’s Books: 13 Titles That Were On Her Shelf”; “What Was On Marilyn Monroe’s Reading List?” They are littered with doubt and objectification: “Did she read them all? I don’t know. Have you read every single title on your shelves?” “Nerds everywhere have drooled over photos of her thumbing through books…”

Umberto Eco, who passed away this month, wrote in his debut novel, The Name Of The Rose, “Books are not meant to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means.” So when I read the museum placard that announced Schneider’s desire for us to “read” the women in her portraits, I felt a pang of reluctance. I’ve never fully accepted Susan Bordo’s arguments for the “body as a text,” yet Schneider makes the veracity of her subjects a starting point. We cannot read these women’s psychic and emotional events, and in most cases, cannot even see what book they’re reading, so we are left with little choice but to read their bodies. Are these bodies to be believed? How many inquisitions must women be subjected to? And indeed, these women are silent—they mean more than what they actually say.

Spending time with the film installation, however, I felt like something radical was happening. I walked into the screening room alone to find Susan, a middle aged woman, reading Jhumpa Lahir’s The Namesake. I watched her breath create soft crests and falls as I became aware of my own breath. Her glasses reflected the pages. I was immediately made aware of two simultaneous gazes, two experiences of reading. I felt engaged with Susan, connected to her, my physiology affected by hers. I was calmed and compelled to cheer her on.

Women are pioneers of durational performance work that is deeply physical, which is no surprise. Women have an intimate awareness of time: our bodies, which we are still fighting for, change in cycles; we are the site of new life, with a nine-month gestation full of physical challenges. While women are bound to time, we have been locked out of literature. A woman reading threatens the man-made Cult of Femininity and societal pressures to nurture others more than the self. Schneider’s film places all of these women within a subversive tradition, an implicit collaboration, and an ennobling demonstration of women’s relationship with both time and literature.

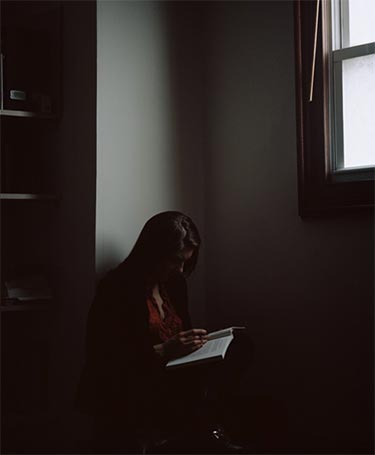

Schneider set consistent requirements for each portrait: All the books in “Reading Women” are written by women. Each woman reads in her home or studio, in a sitting, reclining, or otherwise resting position. She sits by a window, a familiar motif in Western portraiture, though Schneider’s floods of light and shadow most resemble Balthus or Vermeer, renowned for their formal technique and notorious for psychologically confounding depictions of female subjects. Each woman holds an actual book, and you almost forget that laptops, kindles, and smartphones exist. She can take notes, but she never utters those responses. She is alone, seemingly devoid of a partner, children, or roommates (save for LaToya and Abigail, who sit side by side on a couch but are photographed separately). Occasionally we see a small pet, like a rabbit or a black cat, nestled in the reader’s lap, bringing to mind pagan Goddesses and their animal daemons. Schneider creates worlds of timeless solitude and infinite reading.

Schneider set consistent requirements for each portrait: All the books in “Reading Women” are written by women. Each woman reads in her home or studio, in a sitting, reclining, or otherwise resting position. She sits by a window, a familiar motif in Western portraiture, though Schneider’s floods of light and shadow most resemble Balthus or Vermeer, renowned for their formal technique and notorious for psychologically confounding depictions of female subjects. Each woman holds an actual book, and you almost forget that laptops, kindles, and smartphones exist. She can take notes, but she never utters those responses. She is alone, seemingly devoid of a partner, children, or roommates (save for LaToya and Abigail, who sit side by side on a couch but are photographed separately). Occasionally we see a small pet, like a rabbit or a black cat, nestled in the reader’s lap, bringing to mind pagan Goddesses and their animal daemons. Schneider creates worlds of timeless solitude and infinite reading.

And each world is carefully staged. Susan’s body draws a diagonal, dividing the frame in a placid field of whites and beiges. Antonia’s stately torso pushes dramatically upward on the left side of the frame, her hair cascading down her orange chair onto her black cats, thunder clapping outside. Brett’s body curves, echoed within the frame by her curling hair, her printed dress, and the pattern of the chaise that supports her.

There is less depth and breadth in Schneider’s work than the title might let on. “Reading Women” sounds universal, but upon viewing its range of subjects, one could imagine mitigating parentheticals like, “Reading (Middle Class, Reasonably Educated, American) Women,” “Reading Women (Under 65 Who Live in Brooklyn),” “Reading (Normalized) Women,” or “Reading Women (Who Were Able to Secure A Safe Space To Be Their Authentic Selves).” When choosing subjects for her project, Schneider enlisted her own circle of friends, a relatively infinitesimal subset of Women. Therefore, we do not see elderly women; we do not see larger women; we do not see trans women (unless they are present but not identified as such); we do not see blind women reading with their fingertips or with visual aid apparatuses; we do not see women with glaring physical anomalies, disabilities, perceived behavioral disorders, or any intimation of an otherwise drastically transgressive view of “Women.” Certainly, a full throttle commitment to the title’s wide range would be difficult to achieve, but not impossible. I give Schneider the benefit of the doubt that her casting choices were not shortsighted, but necessarily limited to allow the real point of her piece to come to the fore. “Reading Women” is not an exercise in diversity, relevant as that would be today. This limited and controlled sample of bodies and spaces allows Schneider to assert other issues and experiences with more focus.

So we are forced, by design or circumstance, to make evaluations based on the categories available to us. These variances highlight race and ethnicity, style choices, environment and background noise, color scheme, and lighting. A game Schneider seems to play is a hide-and-seek of legible titles. In Schneider’s photographs, most of the books are positioned to obscure the cover or spine—but a select few place those in clear view: Cauleen reads Blacks by Gwendolyn Brooks. Sarah reads Every Tongue Got To Confess: Negro Folk-Tales From The Gulf States by Zora Neale Hurston. Bianca reads Ariel by Sylvia Plath. Cauleen and Sarah are black women. Bianca is pale and blonde. Schneider “matches” her books to their subjects as if to substitute a book for the mirror (another ubiquitous trope in female portraiture). Instead of gazing at her own reflection, Cauleen, Sarah, and Bianca seem to reflect on their cultural inheritances.

Does Schneider give us the opportunity to witness women creating, like Sontag, the texts before them? Are we creating the women as we witness them? And if so, are we not left where we began, projecting what Marilyn is thinking? We do not know if the women chose these books, if they finished them, or what they made of the text. Impulse and response are cut out of the portraits—we only get two pages with each book and body. We are confronted with the present, with our own act of reading the participants before us. Schneider succeeds in creating a compelling aesthetic experience which, watershed though it is not, engages a political movement and philosophical discourse. I am still torn between what Schneider asks us to do with “Reading Women,” and how it made me feel as a woman who cares about women who read deeply.

Carrie Schneider: “Reading Women” will be showing at Marquette University’s Haggerty Museum through May 22.