There’s a scene in the Coen brothers’ underrated 2016 film Hail, Caesar! when brassy 1950s starlet DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson) is shooting a synchronized swimming film. She rises from the water, crown perched on her head and staff clutched in her hand. She beams at the camera. Moments later, she drops her movie star veneer and gets down to brass tacks with the studio’s “fixer” (Josh Brolin), who is helping her with the pesky problem of a child conceived out of wedlock.

Squint and it’s easy to see where the Coens may have found inspiration for their scene: Thomas Hart Benton‘s painting “Hollywood”(c. 1937-38). Though Hail, Caesar!‘s fictitious Hollywood and Benton’s “Hollywood” are separated by several decades, both works share obvious visual cues and a deeply cynical (yet still reverent) insider view of Hollywood. Tinseltown’s glamour is only screen- and canvas-deep.

Benton is the subject of Milwaukee Art Museum’s engrossing “American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood,” the first major exhibition on the artist in more than 25 years. Benton was already one of the most famous artists in America by the time he made his way to Hollywood in 1937, on assignment from Life magazine, but his tricky relationship with the ascendant art (and machinery) of motion pictures is the main subject here. “I am not a Hollywood news column fan,” Benton wrote, “and I have not read any books about the place. I know it only through the direct experiences of an artist interested in making pictures of America and American things.”

“Self-Portrait With Rita” (c. 1922) sets the tone of the exhibition, with Benton, in a not-so-sly bit of self-promotion, depicted as a dark and dashing Hollywood heartthrob. It’s a perfect example of Benton’s Old Master painting traditions and his affinity for silver-screen flair. Overly dramatic compositions and exaggerated, often rubbery poses seem to mimic the heightened silent film acting styles of the era.

It’s not hard to see Benton’s subversive agenda in the epic-sized “Hollywood,” a firsthand behind-the-scenes peek at the 1937 film In Old Chicago. Dozens of workaday technicians and craftspeople surround a scantily clad actress, their presence pulling back the curtain and putting the “factory” in “dream factory.”

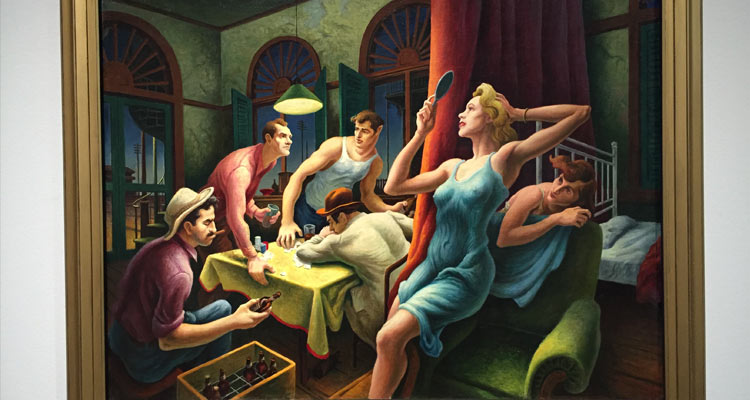

Benton may have been suspicious of the Hollywood machine, but he remained a sought-after artist within the industry. “Poker Night” (c. 1948) was commissioned by Hollywood producer David O. Selznick, and depicts a crucial scene in the film version of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire. Director John Ford, meanwhile, tasked Benton with creating promotional materials for the 1940 film adaptation of The Grapes Of Wrath. Later, in 1954, Benton painted the poster for The Kentuckian, starring Burt Lancaster. It’s telling of Benton’s standing as an artist that the poster depicts his illustration in a frame.

Elsewhere, “American Epics” covers other periods of Benton’s career. Four walls surround the open center of the exhibition hall, each containing multiple panels from the so-called “Indiana Murals.” These bold, pulpy depictions of Indiana life were created for the “Century of Progress” exposition at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, and generated a fair amount of controversy for their unflinching depictions of some of the more ugly moments in the state’s history, including Native American genocide, slavery, and more.

Benton wasn’t immune to his own ugliness. His depictions of African-Americans were often caricatured and stereotyped. Caught up in the patriotic fervor of World War II, he also created wildly racist and over-the-top paintings of Japanese soldiers; in one completely bat-shit piece, the Axis powers are seen spearing a crucified Christ while an enemy aircraft blasts him from above. The exhibit wisely includes these works, refusing to give Benton a pass.

Still, Benton’s love-hate relationship with Hollywood is the main draw of “American Epics.” Character studies, sketches, clay models, and spot-the-reference film clips are used to fill in that relationship. It all adds up to a portrait of an artist inspired by the movies, as well as a glimpse of how the movies were in turn inspired by him.

“American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood” is on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum June 10-September 5, 2016. Express Talks are scheduled for Friday, July 1 at noon and 5:30 p.m. A Film Series, “American Epics on the Silver Screen: A Streetcar Named Desire,” is scheduled for Friday, July 8 at 6:15 p.m.