The four-story, Cream City brick building on 4th Street known as Turner Hall is well known for hosting a wide variety of shows that range from concerts to comedians to live wrestling. Turner Hall also hosts garage sales and craft fairs, along with weddings and a wide variety of other events. However, Turner Hall also holds a gymnasium, complete with a two-story rock climbing wall. This Downtown Milwaukee landmark was built more than a century ago, spurned by an immigrant group that had revolutionary ideals that inspired change. Along with this new group came one of Milwaukee’s most notable women.

Turner Hall was built in 1882 by architect Henry H. Koch—a German immigrant—who also designed Milwaukee’s City Hall and the Pfister Hotel. The building was home to the Milwaukee Turners, or Turnverein, a group of German immigrants that encouraged the development of “a sound mind in a sound body” through education and physical fitness. Many of the Milwaukee Turners were members of a larger revolutionary group known as the Forty-Eighters, a group of political refugees that fled Germany following failed social and political reforms in 1848. Back in their homeland, the Turnverein groups were formed as early as 1811 and supported a unified Germany, a more democratic government, and increased human rights. The Turnvereins set themselves up as underground training groups, teaching gymnastics as a guise for military training in preparation for revolution. Along with physical fitness and sport, the Turnvereins discussed leftist social and political issues and ways to make progressive change in the clubs.

When the Forty-Eighters settled in Milwaukee, they brought many of their beliefs with them and found the United States to be a more hospitable environment for expression. One of these new residents, Mathilde Anneke, continued her work for social justice in Milwaukee and made a substantial mark in women’s history.

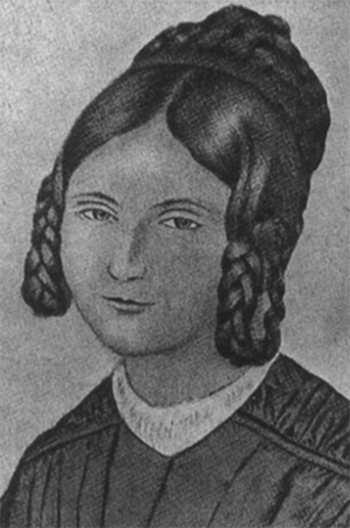

Anneke, birth name Mathilde Franziska Giesler, was born on April 3, 1817 in Lerchenhausen, Westphalia, a region of present day Germany. Her upbringing was one of nobility. She was raised on her grandfather’s estate and married a wealthy wine merchant named Alfred von Tabouillot. This marriage ended in divorce, allegedly due to her husband’s excessive drinking and abuse, which left Mathilde and her child alone.

As a wife and a mother, Mathilde had no rights compared to that of her ex-husband. She was granted custody of their child and left into poverty. She struggled to survive as a single mother and started writing short stories and dramas for almanacs and newspapers. It was through her newfound personal struggles that she began aligning herself with the efforts of the leftist liberal movement in Germany. Suddenly without status, income, or rights, she began to question the rights and roles of women in German society.

As a wife and a mother, Mathilde had no rights compared to that of her ex-husband. She was granted custody of their child and left into poverty. She struggled to survive as a single mother and started writing short stories and dramas for almanacs and newspapers. It was through her newfound personal struggles that she began aligning herself with the efforts of the leftist liberal movement in Germany. Suddenly without status, income, or rights, she began to question the rights and roles of women in German society.

Mathilde later married Captain Fritz Anneke, a former Prussian military officer with similar ideals. She moved with him to Cologne, where they started a daily political newspaper for working class families, soldiers, and farmers called Neue Kölnische Zeitung, in which they covered oppression, social justice, and equality. They published their newspaper with the adopted motto “Prosperity, Freedom and Education for Everyone!” Mathilde and Fritz ran and edited the newspaper, with Mathilde using a male pseudonym since radical women writers were not commonly accepted at the time. Soon after, Fritz was imprisoned for giving a revolutionary speech in Cologne in front of thousands of spectators. In his absence, Mathilde ran, wrote, and edited their newspaper. But it was not long until their publication was shut down by the authorities. In response, Mathilde printed a new leftist publication supporting the revolution and women’s rights titled Frauen-Zeitung, Germany’s first feminist newspaper.

After his release, Fritz joined the uprisings during the German Revolutions of 1848-49 and fought in the Palatinate against Prussian forces. These uprisings challenged repressive regimes and supported democracy. Mathilde, trained in horsemanship, went to the battlefield on horseback with her husband as his orderly. She also continued her writing and kept a diary of her firsthand experiences. Mathilde was even so brazen that she volunteered to deliver messages to and from command posts, despite the negative attention she received as a woman on the battlefield. However, the revolutionary forces were weak and the Prussian military crushed the uprisings in the Palatinate and Baden, putting an end to the revolts in 1849.

Like many other Forty-Eighters, the Annekes and their two children emigrated to the United States and settled in Milwaukee. Mathilde continued her writing and became heavily involved in equality for women in America and the suffrage movement. An avid Union supporters, Fritz fought with 34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment and earned the rank of Colonel. During this time in Milwaukee, Mathilde published the first feminist journal in America, Die Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung, translated to English as German Women’s Times. The first edition of her newspaper was published by a local printer that employed all males. Women did not often work outside the home during the mid-19th century, and in line with her beliefs, Mathilde hired women (including her daughter) to be the typesetters during the printing of her newspaper. The men at the press soon felt threatened with women working by their side and quickly organized and all-male typographers’ union to safeguard their jobs.

The eventual shutting down of Mathilde’s newspaper only increased her drive to fight for women’s rights. In search of funding to create her own press and print shop, she set off on a national lecture tour to raise money. Sponsored by the Milwaukee Turners and a few other groups, she lectured across the Midwest and East Coast addressing equality for women under the law and the suffrage movement. Eventually, she received funding in New York City to continue publishing her newspaper. Through these tours, she met Susan B. Anthony and Cady Stanton, and even lobbied in Washington D.C. for their cause.

Upon her return to Milwaukee, Mathilde founded a girl’s academy called the Milwaukee Tochter Institut. Her school, unlike others in the area, held no ties to any specific religious organization. Mathilde wanted her school to teach liberal arts with a humanistic education. Rather than memorization of numbers and facts that was common practice in education at the time, she wanted her students to develop critical thinking skills. At the academy students were taught a variety of courses—all in German—that included traditional subjects such as grammar, spelling, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, and natural sciences. However, special courses allowed students to diversify their already extensive education with English, French, Latin, music, and drawing. It was at this school that Mathilde would educate youth for 18 years until her death in 1884. She is buried in Milwaukee’s Forest Home Cemetery.

The fight for women’s rights continues across the United States and the globe. Bold beyond her years, Mathilde Anneke supported a revolution in Europe in hopes of advancing the daily lives of women and the working class, which later forced her and her family into exile. Rather than be content in her new homeland, she continued to fight against injustices towards men and women alike, while providing educational materials and schooling for Milwaukee’s future. It is because of these endeavors that Mathilde Anneke is a prominent part of Milwaukee history.