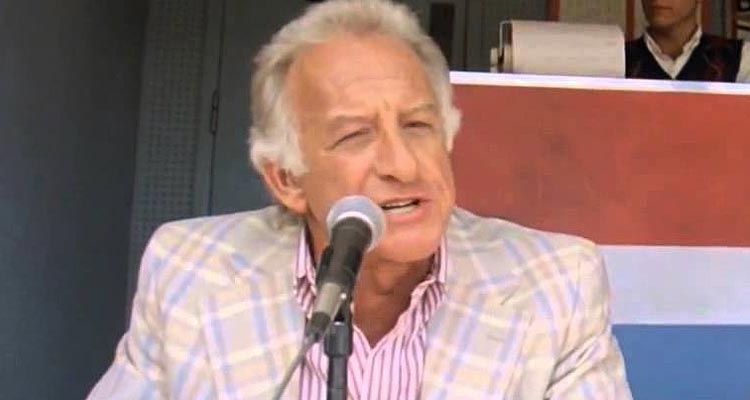

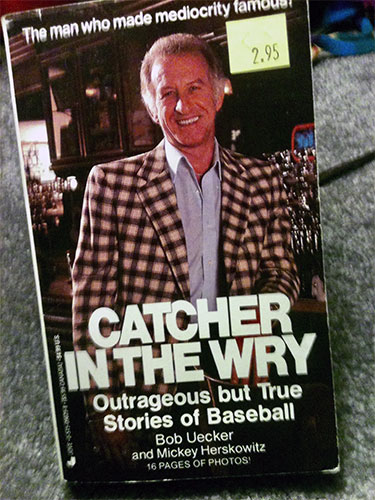

It may have been lost in the glory of Harvey’s Wallbangers and a charge to the World Series, but on August 24, 1982, incomparable Brewers’ play-by-play man Bob Uecker published his autobiography: Catcher In The Wry. His book was overshadowed by the feats of Rollie Fingers, Robin Yount, and Paul Molitor. It was all for the best, though. Nobody excels at getting lost in the glory quite like Bob Uecker.

Pronounced the same as J.D. Salinger’s iconic Catcher In The Rye, the Milwaukee native’s titular pun was so sharp it could’ve spiked a shortstop blocking second base. The main character from that other Catcher book, Holden Caulfield, isn’t entirely different from Bob Uecker. Maybe that seems like stretching farther than Jake Taylor did to leg out that bunt single in Major League, but it’s true. Both Holden and Bob are misfits who struggled in school and cut loose with booze benders. Each stood as individuals in the ’50s, a decade known for conformity. They shared cognizance of the absurdity of life, but they diverged in how they handled the storm. Holden sulked alone and charged his fellow humans with crimes of being phony. By contrast, Bob embraced absurdity, befriended it as though it was a kooky teammate.

From Uecker’s puckish adolescence to the unlikely rise of the Bob Uecker Fan Club to his ascendance to the broadcast booth, Wry is filled with stories that make us grateful for the misfits.

Bob delights with tales of sabotage, like when he had a prickly manager who forbade his lowly players from eating his “gourmet” chili. Bob bristled at the cold elitism. When the coast was clear, he would spike the vat on the stove with matches and cigarette butts, then watch from afar, snickering and high-fiving as coaches and members of the press as the skipper scarfed down the new, tar-enhanced recipe.

When a callous pitcher insulted him during a visit to the mound, Bob shrugged, returned to the plate, and told the batter which pitch was coming next.

Bob also made a mockery of the tuba. He was like an overgrown Bart Simpson, except with curls instead of spikes.

Honesty is vital to a good memoir, and Uke is astutely self-aware throughout Wry. Beneath his deadpan humor is a truthful man with no delusions. During his stint in “the show,” Ueck wisely preferred to be a benchwarmer. He writes: “The less I played the more likely I was to stay in the big leagues.”

Catcher features an array of other choice Ueckerisms:

Catcher features an array of other choice Ueckerisms:

“My father wanted me to learn a trade. I did. By the end of my first semester I could hot-wire a car.”

“Fans often ask me how the players were able to stay up, stay ready, when it was August and the sun was blazing and your team was out of the race? I can only answer for myself. I would just go out and get likkered (sic) up.”

“You have to be lucky. It isn’t enough just to be crazy.”

But an especially telling line comes when the author describes waking up the morning after a night of brawling and binge drinking: “I felt like I had the hangover they were saving for Judas.”

It’s an exemplary sentence on life in Wisconsin, with the wonder and the punishment of religion and alcohol found in the same concise passage. And of course, there’s a wild story behind it.

Ueck had gotten rowdy and thrown punches at the Cock ‘n’ Bull restaurant in West Palm Beach during spring training, along with two fellow Braves, both starters in the lineup. The snarky backup catcher was clinging to a roster spot, with his broken throwing arm in a sling (which didn’t stop him from jabbing with his left), and when news of the brouhaha broke on the radio, a hungover Uecker sensed trouble. Sure enough, two of the players wound up keeping their jobs. Neither was named Bob.

That donnybrook marked the end of his playing career, but the great ones know how to adapt. Mr. Baseball was only getting to the midpoint in the memoir he penned 35 years ago.

Sometime after the fracas, the brass in Atlanta threw him a life preserver. Acknowledging his wit, charm, uncanny blend of swagger and humility, and the fact that nobody wanted him to play baseball anymore, the Braves gave Uecker a job in public relations. He thrived. The gig led to public speaking, announcing, and a seat beside the desk of Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, where Ueck captivated and slayed without cracking a smile. Hollywood awaited him—and so did Milwaukee.

Three years before Mr. Belvedere started writing him paychecks, and seven prior to his hysterical role in Major League, Uecker and collaborator Mickey Herskowitz wrote a wickedly funny depiction of the man who made mediocrity famous. A follow-up was printed in 1992. Punning the classics again, Ueck titled the sequel Catch 222. It didn’t fare well. The book is harder to find than a Cardinals fan who’s worth talking to. Thus, Catcher In The Wry is Uecker’s magnum opus.

Milwaukee holds the highest esteem for the voice of the Brewers, and today, we tip our caps to his prose.