One enduring horror character that refuses to die is Norman Bates, former star of Psycho (as well as various sequels and remakes), and current star of reboot prequel show Bates Motel (which has a series finale May 11 on A&E). The character was created by horror writer Robert Bloch, who spent his formative years living on Milwaukee’s East Side.

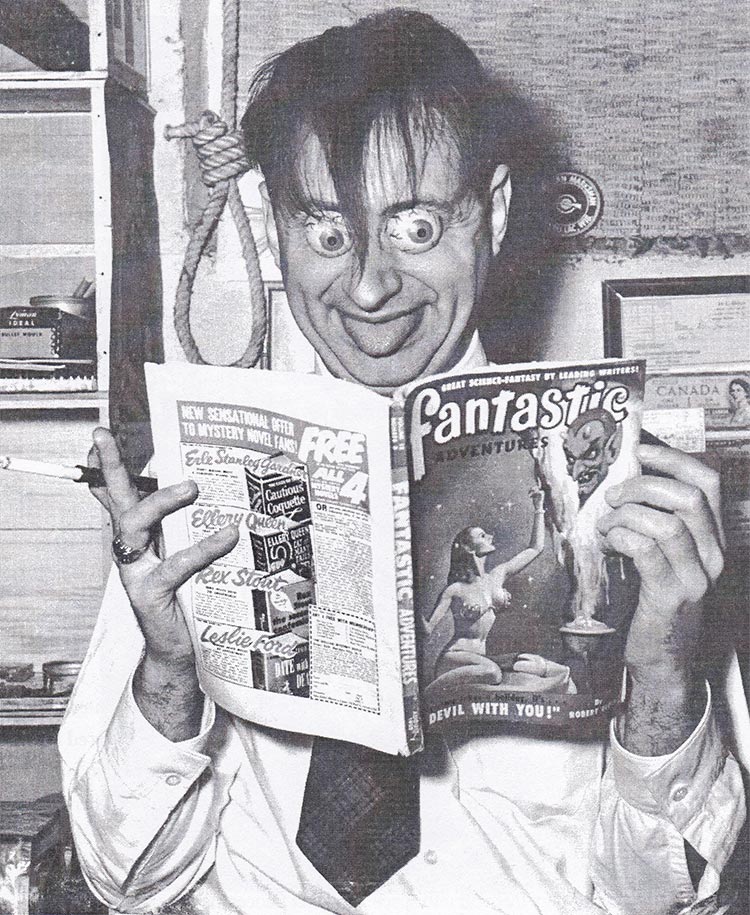

Bloch’s early work was derivative of his favorite writer, horror legend H.P. Lovecraft, but as time went on, he developed his own voice. Bloch specialized in stories of psychological horror, often with a healthy dose of morbid, goofy humor. Think Mel Brooks meets Stephen King. One of his stories was named “Time Wounds All Heels,” and he titled another collection of short stories Stuff Such As Screams Are Made Of.

Bloch lived in Milwaukee from 1929-1953. During that period, he left an interesting mark on the city, and not just for his ghoulish stories.

H.P. Lovecraft encouraged Bloch to be a writer

Robert Bloch was born in Chicago, but his parents moved to Milwaukee in 1929, when Bloch was 12 years old, to pursue new work opportunities. The Bloch family settled into an apartment on East Knapp Street. Bloch recalled in his pun-filled 1993 autobiography Once Around The Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography that his biggest youthful thrill was reading a monthly pulp magazine named Weird Tales. On the first of each month he would wake up at the crack of dawn so he could run down the street to the Ogden Smoke Shop. There he would plunk down a quarter, one-quarter of his monthly allowance, for a copy of the magazine.

Bloch’s favorite Weird Tales writer was a man from Providence, Rhode Island, named Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Although he is regarded today as one of the most important figures in American horror writing, he was little known at the time except to avid readers of the magazine. Eager to read more of his work, Bloch sent him a letter care of Weird Tales, asking where he might be able to find more of his stories. To his surprise and delight, Lovecraft not only wrote back, but gave a detailed listing of his magazine stories and offered to send him some tear sheets to borrow and read.

“The notion that a full-fledged adult literary celebrity would make such an offer to a half-fledged teenage non-entity was as astounding to me as it was commonplace to Lovecraft,” Bloch wrote.

The two began a correspondence and the writer introduced Bloch to the “Lovecraft Circle,” a group of pulp writers who developed friendships through frequent letters. Lovecraft encouraged Bloch to try his hand at writing and after a couple failed attempts, Bloch sold his first story—“The Secret Of The Tomb”—to Weird Tales in 1934.

Although the two writers never met, their friendship grew so much that Bloch paid tribute to Lovecraft by featuring him as a character in a Weird Tales story he titled “The Shambler From The Stars.” In it, a character representing Bloch visits a stand-in for Lovecraft at his home in Providence. The two puzzle over an ancient evil and eventually, Lovecraft’s character is devoured by a creature “bloated and obscene; a headless, faceless, eyeless bulk with the ravenous maw and titanic talons of a star-born monster.”

Lovecraft was delighted and retaliated with a sequel, “The Haunter Of The Dark,” in which a “Robert Blake” returns to Providence only to meet his own gruesome demise. In case there was any doubt that Blake was Bloch, Lovecraft listed his actual Milwaukee address at the time—620 E. Knapp Street—in the story.

Lovecraft almost couch surfed in Milwaukee

Another member of the Lovecraft Circle was prolific Wisconsin writer August Derleth, who lived in Sauk City, Wisconsin. Derleth wrote in a variety of genres: nature poetry, mystery, non-fiction, and novels that reflected small town life. He also had a passion for “weird fiction,” as the genres of horror, sci-fi, and fantasy were commonly known then. Like Bloch, his first published story was in Weird Tales (“Bat’s Belfry,” 1926) and his fandom of Lovecraft led Derleth to be a friend and correspondent.

Lovecraft introduced Bloch to Derleth, who was not immediately impressed with Bloch’s writing skills, but they soon became friends and would take day trips to visit each other. Bloch recalls that in one of his visits in 1937, he and Derleth had an exciting discussion in which they planned to subsidize a trip for Lovecraft to the Midwest that summer. Lovecraft would be brought in by train to Milwaukee, where he probably would have crashed on Bloch’s couch (or stayed with one of his friends). They planned on taking him to Chicago to visit the Weird Tales office and then out to stay with Derleth in Sauk City.

Bloch and Derleth were thrilled at the idea of having Lovecraft visit Wisconsin, but their dream came to an end on March 15, 1937. Bloch got a somber phone call from Derleth: Lovecraft, age 46, was dead. The poverty stricken writer died from cancer of the small intestine and malnutrition.

Although Lovecraft never made it to Brady Street, another of Bloch’s famous friends did. After getting married, Bloch moved out of his parents’ house and into an apartment above the old Glorioso’s location at 1018 E. Brady Street. There, he was visited by his friend and future sci-fi legend Ray Bradbury.

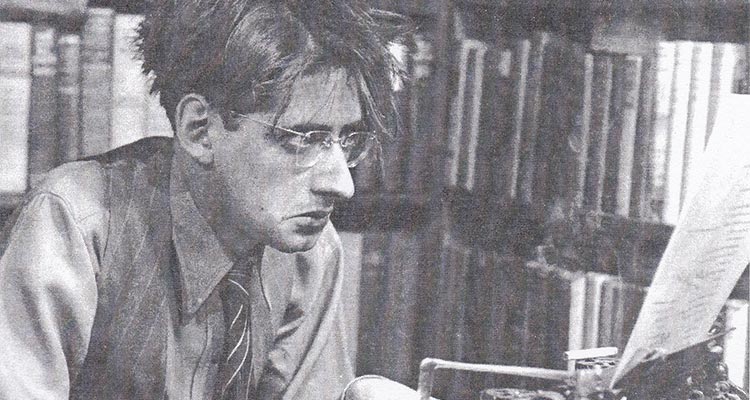

Bloch’s first books were published while he was an East Sider

Lovecraft’s death inspired Derleth to publish a collection of his stories from Weird Tales. After being rejected by several publishers, Derleth decided to start his own homemade publishing imprint, Arkham House. He launched the imprint with the first collection of stories by H.P. Lovecraft in 1939, The Outsider And Others.

From his home office in Sauk City and a crowded guest room filled with inventory, Derleth went on to publish a number of notable titles with Arkham House: the first book by Ray Bradbury (Dark Carnival, 1947), an early book by Robert E. Howard (creator of Conan the Barbarian), the first book by fantasy and sci-fi writer Fritz Leiber, Jr., and later the first book by horror writer Ramsey Campbell, among others.

Derleth also published Bloch’s first book, a collection of stories that appeared in Weird Tales and similar pulps titled The Opener Of The Way, in 1945. Bloch’s first novel, The Scarf, followed in 1947 from Dial Press. Bloch would go on to write over 30 novels and hundreds of short stories.

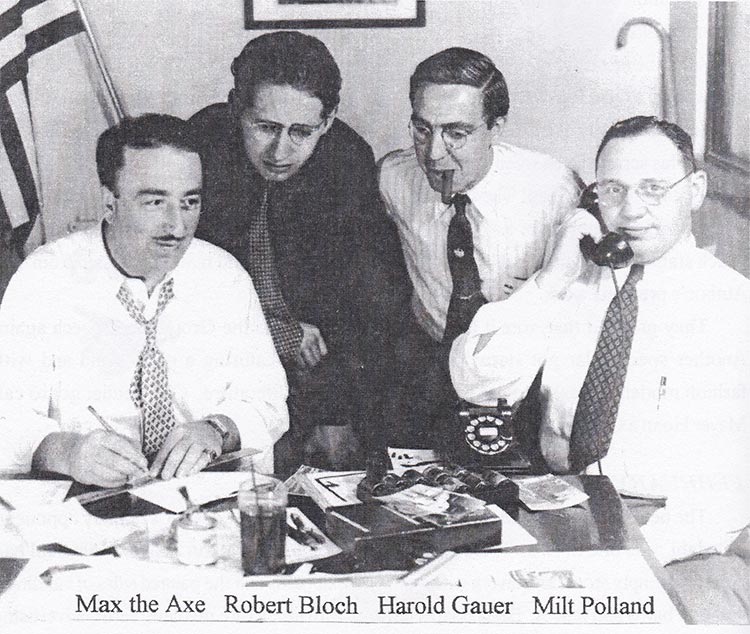

Bloch’s Mad Men style team helped elect Carl Zeidler Milwaukee mayor in 1940

Before Bloch moved to Brady Street, he had already been hanging out there frequently. His friend Harold Gauer ran his Precision Process Photographers business from the attic of a building his parents owned on Brady. The building also housed the family business, Vernie’s Homemade Candy Shop, and the family’s second-floor flat. “The Lab,” as it was known, was a place where Gauer, Bloch, and friends kept a journal of their activities, took funny photos, drank beer, and collaborated on ridiculous, unpublished fiction.

One of Bloch’s friends offered him and Gauer an unusual gig: working as the brain trust on the campaign of assistant city attorney Carl F. Zeidler, who wanted to enter the 1940 race for Milwaukee mayor. Zeidler and several other candidates were attempting to overthrow Daniel Hoan, who had been mayor for six terms.

Gauer’s photography skills and Bloch’s creative writing abilities launched an innovative campaign that thrived on publicity stunts and media attention. With a limited budget, they produced a booklet that featured photos of Zeidler talking to the “man on the street,” and organized a grandiose candidacy announcement speech at the South Side Armory (located on S. 6th Street) featuring an orchestra, chorus, and a balloon drop with a thousand balloons at the end of the speech. Nothing unusual by today’s standards, but it was new and exciting for a local election at the time.

Bloch’s team also dreamed up some sly gimmicks. At one speech, Zeidler wheeled a model of city hall onstage and symbolically dusted and dismantled parts of it to emphasize his points. When Hoan gave a speech at Bahn Frei Hall (formerly located on W. North Ave.), Zeidler responded “live” at Jefferson Hall (formerly housed on W. Fon du Lac Ave.) by having a person run notes to someone on a payphone in Bahn Frei Hall’s lobby. The info was relayed to Bloch, on a phone underneath the stage at Jefferson Hall, who rang the info up to a phone next to Zeidler onstage, who zinged Hoan for what he had just said at his speech across town moments before.

The press ate all of these antics up, and Zeidler got tons of media attention. It paid off: Zeidler first advanced in the primary and then made a surprise victory over Hoan, winning by over 12,000 votes.

Bloch contended that he and his team got shafted and didn’t get paid their promised salary by the Zeidler campaign. He did find further work in downtown Milwaukee with the Gustav Marx Advertising Agency, and worked there for several years. Zeidler resigned as mayor two years into his term, because he wanted to enlist to fight in WWII. He joined the Navy and his ship, the SS La Salle, and all hands were reported missing in 1942. Zeidler was “officially presumed dead” in 1944.

Bloch blindly sold the movie rights to Psycho to mystery bidder Alfred Hitchcock

It’s been erroneously reported that Bloch wrote his best known work, Psycho, while he lived above Glorioso’s on Brady, possibly while eating their famous deli sandwiches. In truth, by 1953, Bloch and his family had moved from Milwaukee to the small town of Weyauwega, Wisconsin. His wife, Marion, was ill and suffering from tuberculosis, and the Blochs decided to move back to her hometown to be closer to her family. Bloch got his idea for Psycho from a shocking true crime story from another Wisconsin small town, Plainfield, the home of Ed Gein. The 1957 case revealed that the mentally ill Gein had robbed graves and murdered two women to make furniture and other artifacts out of human body parts. Bloch’s character Norman Bates, lonely proprietor of the Bates Hotel, is a reclusive weirdo and fond of human taxidermy, just like Gein.

Psycho was published in 1959 by Simon & Schuster, and Bloch’s agent got a call from MCA talent agency, representing a party interested in buying film rights to the book.

“The offer was blind: the would-be buyer’s name was not mentioned, only the price—five thousand dollars,” Bloch wrote. The offer was negotiated up to $9,000. After his agent and publisher took cuts and taxes, Bloch got $6,750 for the film rights. The unnamed director, as Bloch found out soon from a newspaper, was master of mystery and suspense Alfred Hitchcock, and his 1960 adaptation of the book is often hailed as one of his best films.

Despite not sharing in the movie’s wealth, the sale was good for Bloch in that it led to more steady (and decent paying) writing work. After the Psycho sale, he moved his family from Wisconsin to be closer to Hollywood in Sherman Oaks, California, and found gigs writing scripts for films and television shows like Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Star Trek. He also continued to write horror novels and short stories until his death in 1994.